|

|

General Topics:

Main Page

| About the Bach Cantatas Website

| Cantatas & Other Vocal Works

| Scores & Composition, Parodies, Reconstructions, Transcriptions

| Texts, Translations, Languages

| Instruments, Voices, Choirs

| Performance Practice

| Radio, Concerts, Festivals, Recordings

| Life of Bach, Bach & Other Composers

| Mailing Lists, Members, Contributors

| Various Topics

|

|

Death in Bach Cantatas

Discussions |

|

BWV 106 & 198 |

|

Ambroz Bajec-Lapajne wrote (October 17, 1999):

Firstly I have to explain and warn that I have no intentions and it would be utterly improper to start another 'tempi-discussion' so I will really shortly explain what I meant with my previous post.

< I don't see your point. These are religious works and should be performed and listened to as such. From which perspective should we listen to it today, whether you are religious or not? Why should it be faster from "today's perspective of death"? Please elaborate. >

The conception of death in the Bach times (as indeed before and later) was a different one that we have nowadays. Today death is perceived as something that people fear and a death experience is for those close to the deceased something extremely sad. In those days death was a salvation from this (unperfect, sinful) world and the beginning of an eternal life in heaven - under a condition of course that you reached it. I do not mean people died gladly, or that they didn't mourn over the deceased. This is what I meant by the saying that since Bach was a very religious person he felt this perhaps even stronger than others (bearing in mind that he was an artist too) did. His funeral music is therefore written in somewhat different motion as we are used today. And if we consider this hypothesis of mine, perhaps we see that the funeral music needs not to be as dark and sad in order to translate it to the cultural language of today. Listen to Purcell Funeral sentences and you will notice the very similar feeling. I hope I haven't been too philosophical, and I might add that I have not been raised in any religion and am an agnostic.

< As has been mentioned on this list quite a while back : Gardiner makes Argenta sound like an angel. She shouldn't be one in BWV 106. Gardiner has his Reformation theology up side down in this one and therefore, IMO, it is a bad performance, no matter the tempi and regardless of how beautiful it sounds. >

I'm not saying that she sings as an angel - for me she is the desperate cry (in the night, if you will) for God.

< If you mean to say it should NOT be performed from Bach's perspective, why should Gardiner bother with HIP? >

Quite 'au contraire' my friend - his interpretation absolutely fits my hypothesis on Bach perception of death.

< Others do/have done a lot of research also and come up with different tempi. Why should he be the only one who's right? >

My, my, you are a militant chap. I never claimed his is the only right one. I personally believe that music is a matter of taste. However, Early Music is a subject to heavy disputes simply because we have so little knowledge of the performance practice. There is enough of so called HIP, so that you have the ability to choose the one you like most. JEG just has that something for me that he persuades me with his interpretation as well as answers my questions rather sufficiently. |

|

Wim Huisjes wrote (October 17, 1999):

(To Ambroz Bajec-Lapajne) Thanks for the clarification. I understand what you mean now, though I don't necessarily agree. I'm still having trouble with the concept of "today's perception of death". IMO today there is no such generally accepted concept. At most, any perception of death is more individually determined than in Bach's time and the society he was part of. One extreme: for some, little has changed. Another extreme: for others Bach's perception may seem as coming from another planet. So, on your conclusion we agree: what we prefer in performances is determined very much individually.

As others do: I also hope Gardiner will record more cantatas. My comment was focused on his performance of BWV 106. |

| |

|

Cantatas which pray for death |

|

Jill Gunsell wrote (October 15, 2000):

This is rather a long post, but I hope our moderator will permit it, because I think the subject is - for some people - central to interpreting Bach's religious cantatas in the modern day.

I forget who wrote, and in connection with which cantata (not that it matters) that they find it hard to identify with the "I long for death - life irks me" theme in some of the texts. It's not surprising that this is a puzzle for many, including those on this list who are not religious or who adhere to non-Christian faiths. Even many Christians find it mysterious that their faith, which preaches and celebrates the beauty of God's creation (despite the problem of theodicy), should from time to time speak of longing to leave this life, if we are sustained in it by a good God.

But it is not a mere anachronism.

Bach's religious music was written to assist - to be - prayer, and of course it still fulfils this function for many people. The question is, how do religious people of today pray a prayer like this? And the question arises in many places, not only in Bach. In the Hebrew-Christian continuum of ancient prayers going back to the Psalms of David and earlier, there is anger, hatred, vengeance, etc., etc., along with all the emotions of the human spirit, directed to God, who is the ultimate recourse for every human instinct, in a praying person.

So how does one respond today to a "politically incorrect" or even a "death-wish" prayer?

First, the basis of the Jewish response - (Aryeh - I write this tentatively and with respect). Judaism's faith in God has always been the paramount fact in interpreting and living in the world as it actually is. The idea of the afterlife in the Christian sense has been rejected or at least downgraded from time to time by the scholars. Even Jews for whom the concept of afterlife (with God) has seemed valid, stress the afterlife itself much less than living a righteous life here and now. Jam Today rather than Jam Tomorrow. [ Jam = being in a right relationship with God :-) ] So praying for death is a problem for the praying Jew. It just does not work.

Second, the Christian response: well, it would be the same as the Jewish response in its first stage. Jam Today is mandated. But there is a second stage. Faith in the Resurrection of Jesus opens up an idea not available to the Jew: the concrete reality of happy life after death. This changes the perspective somewhat, for the better in some ways, but it also creates a moral problem for the Christian: it is now all too easy to go for the Jam Tomorrow option. This is how many read these Christian prayers of Bach.

Sorrow for personal sin and longing for a sinless (and therefore entirely happy) existence was undoubtedly the dominant motif in the Lutheranism of Bach's day, but it is not the only way to read these prayers. This must be so, because people of today for whom that theme is not dominant find these prayers quite valid. So, how?

Well, of course, some people simply did and do long for death, which we have to accept. But that cannot apply to all those who pray Bach's cantatas in our time. So what is going on here?

There is a deep tradition in Christianity - growing directly from Judaic prayer - of solidarity with others in (during) prayer. For example, the "vengeance Psalms" are prayed regularly in both communities, yet both recognise the truth of "vengeance is mine, says the Lord" and both preach mercy in the name of God. But some people do want revenge, and those who do enter into the prayer of those who do not. Prayer is never a solitary act. All prayer unites the pray-er with God so that all pray-ers are united in God. The pray-er who is not vengeful, is praying with and on behalf of the one who does want revenge. The one who prays a prayer of despair but is not desperate, is praying with and on behalf of the one who despairs. The one who loves life, prays with and on behalf of the one who hates life.

The dominant Lutheran preoccupation with hatred for one's own sin, personal contrition and personal redemption, may be interpreted from the outside as very much like a death-wish. It may even seem to - or actually - verge on the Albigensian view if taken too far: Jam Tomorrow becomes so important that suicide seems almost the only sensible course. But this is not fair to the Lutheran who recognises that the task the Christian is to carry the cross of suffering in this world (one's own and/or that of others). Longing for the suffering to stop, and for fulfilment in happiness, Bach's Lutheran bravely shoulders the cross anyway - but allows himself a complaint.

In the non-Lutheran Christian prayer tradition, as indeed in the specifically Lutheran, there is undoubtedly a longing to "run to God", recognised as the Ultimate Good. This is reasonable, given that the ultimate destiny of every person is seen as union with - eternal experience of - absolute truth, beauty and goodness. Bach certainly expresses this. There is, though, an imperative not to take this feeling too far, and so waste or undervalue life here and now, which is key to our experience of God both in its own terms and as our "formation for eternity".

Another important aspect of the response (in prayer) to Bach is more community-facing. As well as prayer "for me" there is prayer "for them". So the daily prayer of the church includes the vengeance Psalms, and the how-can-you-do-this-to-me, yelling-angrily-at-God Psalms, but it is (supposed to be!) solidarity with - expressing the cry of - those who have no voice to cry with, or who do not believe their cry is heard. One even voices (while not sharing) their genuine death wish or hatred of life, because that would be their prayer if they were not too overwhelmed to pray at all. "Pray as you can and not as you can't." They can't, so we do. We voice their desperation and enter into it as far as we can, in order to ask God for its transformation into hope.

For people who are moved by the texts of Bach's religious cantatas but do not have religious faith, I imagine that such "solidarity" responses are involved, but without reference to a God they cannot envisage. There is also the same movement of the soul "upwards", as it were: a longing for a better way of existing, for freedom from suffering, but not towards a personal God. The overwhelming humanity of Bach prompts such responses.

In Bach, when I hear the plea for death, I think of those who are actually crying for death, now, unlike me. Of those who cannot hear Bach, let alone pray with him. Who have no hope. Bach moves me to tears - for them.

No doubt there are endless ways of responding to Bach's (words and) music both in prayer and without prayer in my sense of the word. It would be very interesting to hear different views. All I know is that, long after his death, Johann Sebastian's work of genius, at the deepest levels of the complex, human soul, goes on and on. |

| |

|

Bach and clocks |

|

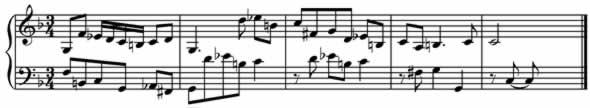

Marie Jensen wrote (October 25, 2000):

I'm not writing this to participate in the debate of tempi in Bachs music. Just to tell that in some of Bach's cantatas dealing with death, clocks are often imitated. The best example I can come up with is cantata BWV 95 "Christus der ist mein Leben", the tenor aria "Ach schlage doch bald". Another example could be the more well known cantata BWV 161 "Komm du suesse Todesstunde" the ending of the alto recitativo "Der Schluss ist schon gemacht" . For me these examples sound like the mechanics of old fashioned clocks.

Tick-Tock! |

| |

|

Perspective of death in bach's vocal works |

|

Thomas Manhart wrote (January 29, 2008):

Coming Sunday we will perform cantata BWV 82 and BWV 158 in Singapore. I plan a pre-concert talk about the perspective of death in bach’s vocal works.

I plan to talk about the common theme of the earth as place of suffering, and death as redemption...thus all the “looking forward to death”, a rather content sounding “Welt ade” etc. I also want to point of the musical patterns for the respective arias , like often the 6/8 timing.

I would be happy to receive some advice from the experts in this group, what you would not want to miss to mention in such a talk.

Many Thanks for your input. |

|

Aryeh Oron wrote (February 3, 2008):

[To Thomas Manhart] The BCW contains two pages dedicated to this topic:

Discussions: http://www.bach-cantatas.com/Topics/Death.htm

Article by Thomas Braatz:

http://www.bach-cantatas.com/Articles/Death-Libretti[Braatz].htm

I hope you will these pages useful for your needs. |

|

Uri Golomb wrote (February 3, 2008):

Two articles of mine on the Bach Cantatas website also touch upon this issue with relation to BWV 82, although they focus on other aspects:

http://www.bach-cantatas.com/Articles/BWV82-Golomb.htm

http://www.bach-cantatas.com/Articles/Sellars%5BGolomb%5D.htm

Perhaps you will find these of use as well. And, of course, there are the discussions of these cantatas on the website, which touch upon these and other issues.

Hope this helps, |

|

Thomas Manhart wrote (February 4, 2008):

Thanks to all who helped. I think we presented quite a nice concert yesterday and I hope the audience felt well informed.

This list is great!!! |

|

Yoël L. Arbeitman wrote (February 5, 2008):

dear death-obsessed beings,

I happened (before this thread) the other day to be listening for the 2nd time to Boxberg's "Bestelle dein Haus". I was much more impressed with both the Boxberg and also with the Riedel cantata on this Ricercar item (most of the set is unavailable and certainly the cheap issue of the 10CD set Deutsche Barock Kantaten, of which this is vol. VI).

At all events, I was struck by Boxberg's "out" after repetition of all the usual Lutheran stuff about oh how wonderful to escape the hell of life and to be dead. Boxberg, after the necessary repetition of this bs., then concludes

Wenn gleich süss ist das Leben,

der Tod sehr bitter mir,

will ich mich doch ergeben,

zu sterben willig dir.

Ich weiss ein besser Leben,

da meine Seel fährt hin,

des freu ich mir gar eben,

Sterben ist mein Gewinn.

Somehow I don't think he believes the 2nd part of this concluding chorale.

Great poetry it ain't.

Nice cantata it is.

Bach's "Bestelle dein Haus" it ain't. |

| |

|

Actus Tragicus - welcome! |

|

Michael Cox wrote (November 3, 2011):

In the unlikely event that any of you are passing through Finland, welcome!

The Finnish composer Sibelius lived in the parish of Tuusula, north of Helsinki, and it has a strong musical tradition. The soloists and instrumentalists are professionals and the choir mostly amateur. I lead the bass section.

Tervetuloa/welcome!

J. S. Bach Actus Tragicus BWV 106

<>

A performance in Israel with the eminent German conductor Frieder Bernius:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rfn5vFFt4Us&feature=related

I want the introduction to this cantata played at my funeral! |

|

Julian Mincham wrote (November 3, 2011):

Michael Cox wrote:

< I want the introduction to this cantata played at my funeral! >

But not yet!! |

|

Michael Cox wrote (November 4, 2011):

[To Julian Mincham] I’ve specified this in my will - I own several recordings, but I’ll leave it up to my son, who is a Lutheran pastor, to decide which one to use when the time comes! This has always been one of my favourite Bach cantatas.

When I first sang in it a few years back when I was recovering from a near-fatal stroke, I was brought to tears, especially by the words “Mensch, du musst sterben”. The opening sonatina is so soothing and comforting. I was standing directly behind the viole da gamba - what a wonderful sound! |

|

Julian Mincham wrote (November 4, 2011):

[To Michael Cox] Last year I was privileged to hear a performance of BWV 106, along with BWV 150 and two other early works in the Blasiuskirche in Mühlhausen, performed on period instruments. Also a highly moving experience. |

|

Douglas Cowling wrote (November 43, 2011):

Actus Tragicus - Crying in Bach

Michael Cox wrote:

< want the introduction to this cantata played at my funeral! >

I want the Bass Recit "Am Abend das es kuhle" and Aria "Mache dich mein Herze" from the SMP (BWV 244).

The Recitative is one of my BTM's (= Bach Tearful Moments) that never fail to reduce me to tears in a performance.

Yes, I was a very sensitive child ... |

|

George Bromley wrote (November 4, 2011):

[To Douglas Cowling] for me Ich hab genug.(BWV 82) |

|

Henner Schwerk wrote (November 4, 2011):

[To Douglas Cowling] I like to have the motet "Komm Jesu komm" (BWV 229) |

|

Thérèse Hanquet wrote (November 4, 2011):

[To Henner Schwerk] I would like BWV 118: O Jesu Christ, mein's Leben Licht

the outdoor's version (with horns and litui)

We will perform it in February :) |

|

George Bromley wrote (November 4, 2011):

[To Thérèse Hanquet] now we have all arranged our funeral music lets do a lot of living. |

|

Michael Cox wrote (November 5, 2011):

George Bromley wrote:

< now we have all arranged our funeral music let’s do a lot of living >

If only we could have all the pieces mentioned at our funerals! Since I seem to have started off this train of thought, I might add that since most of my friends and relatives do not understand German, a German text would not “speak” to them, so I have indicated in my will that the said instrumental introduction to Actus Tragicus (BWV 106) would be a subtle reminder to those who know the piece that we all have to die sometime. I have also indicated that Handel’s “I know that my redeemer liveth” might be sung (perhaps by my daughter-in-law). My wife’s own Handel solo numbers in the past have been “How beautiful are the feet” from Messiah and “O Wretched Israel” from Judas Maccabaeus, but these wouldn’t be appropriate.

Both Bach and Handel pointed beyond death to eternal life with Christ. That’s where they found their strength to live. |

|

George Bromley wrote (November 5, 2011):

[To Michael Cox] <> |

|

David McKay wrote (November 5, 2011):

[To Melanie Bromley] Speaking of music for one's funeral, my Aunty Ruth died last year, at the age of 100.

She specified a hymn which almost none of us knew. I think it was "Eternal Light, Eternal Light, how pure the soul must be."

A few of the older folk there had sung it years ago, but none of us could sing it confidently.

While I'd like to attend a funeral where the beautiful music of Bach is performed for a congregation of folk to whom it actually means something, I think I'd rather the folk at my funeral sing a song or two of their choosing that means something to them.

And in my 60th year, I also hope it is years and years away. |

|

Ed Myskowski wrote (November 6, 2011):

<> |

|

Jyrki Wahlstedt wrote (November 7, 2011):

<> |

|

Jyrki Wahlstedt wrote (November 7, 2011):

<> |

|

Ed Myskowski wrote (November 8, 2011):

<>

I also shed an occasional tear over Bach, especially when contemplating music for my funeral. |

| |

|

Bach and death |

|

Continue of discussion from: Cantata BWV 82 - Discussions Part 8 |

|

Matthew Laszewski wrote (November 13, 2012):

This cantata is serene. The depth and height of that serenity are nearly unparalleled. But, I do not understand the "longing-for-death thing" as an interpretation of its music or words. This is surely acceptance of suffering in life and freedom from the fear of death:"Oh death, where is thy sting; oh grave, where is thy victory?" is how Handel celebrated freedom from death in the Messiah.

Death is and was inevitable. For a follower of Christ, it no longer had to be feared; for the true believer - Simeon who saw Christ with his own eyes, it can be welcomed (when it comes because the redeemer, the messiah has come). Mortality is a fulfillment.

For the rest of us, death or life after death is no longer unknowable or hell, but glorious. To those who were surrounded by death, disease and dying everyday of their lives (as was JS Bach), this surely was "the good news" of the gospel. One is ready to die because one no longer need fear it. It will come, so let it.

The Canticle of Simeon (Nunc Dimittis - Now dimiss thy servant, i.e., Take me Lord) is the inspiration for this cantata and was for me and fellow 1960s teenage boys in high school at a Franciscan Friary where nightly at Compline we chanted the Canticle and the following responsory thrice: "In manus tuas, Domine, commendo spiritum meum" (Into thy hands, O Lord, I commend my spirit). We got the message. Immediately after we sang our bedtime prayer, "Before the ending of the day, Creator of the world we pray, that with thy wonted favor thou, wouldst be our guard and keeper now... etc. And finally, "Keep us oh Lord as the apple of thine eye, and protect us under the shadow of thy wings". We may not have been devout, but all saw that death like sleep is followed by an awakening; that we had protectors if we sought them and honored their precepts.

Death is not an ending if you say your prayers and are sorry for your sins. Jesus has shown us the way to accept all that god gives us – including misery, sorrow, joy and death.

That is powerful stuff and Bach created BWV 82 and BWV 199 and so very much more to celebrate, the way(penitence) and the truth(life everlasting) that grant us freedom the cycle life and death which ultimately allows us to accept it without reservations. |

|

Julian Mincham wrote (November 13, 2012):

[To Matthew Laszewski] Bach's output of religious works is shot through with the very human dichotomy that, especially for those who believe in an afterlife death is, on the one hand, something to be longed for; on the other it is something that causes much sorrw and is even to be feared. Whilst one of his best essays on death is BWV 8 (when, Lord shall I die?) I would suggest that those interested in this theme look at the less well known BWV 156. The second movement is a duet incorporating a chorale in which time stands still as the dying one stands 'with one foot in the grave'.

I am loathe to go into further detail as Bach's attitude towards death is a theme I am developing in what may become a (hopefully) fairly major work at the moment. I am, however, always interested in hearing other people's reactions to the notion of death as portrayed in his music.

And would I be alone in finding Bach the most consoling of all composers in times of personal loss and grief? |

|

Douglas Cowling wrote (November 13, 2012):

Julian Mincham wrote:

< I am loathe to go into further detail as Bach's attitude towards death is a theme I am developing in what may become a (hopefully) fairly major work at the moment. I am, however, always interested in hearing other people's reactions to the notion of death as portrayed in his music. >

Modern sensibilities don't have much sympathy for the historically-conditioned world view of Bach towards death. Some just deny the literal meaning of the music. "Bist du bei mir" (still popularly atrributed to Bach) is regularly requested at weddings even though it is a funerary song addressed by the dying soul to Christ, not the groom to the bride.

The more sophisticated suggest that Bach's universalism "transcends" his age, and the music "means" something other than what it says. We see this at work constantly in discussions of anti-Semitism in the Passion tradition

which Bach inherited. Bach's music is too beautiful and affecting to be so sordid.

I remember hearing a lecture about funeral customs among 18th century Lutherans. The academic audience was alternately derisive and uncomprehending as the speaker described how girls in Bach's time had two "hope" chests: one for their wedding and one for their funerals. It was a social occasion for them to gather, sing a few funeral hymns and then gossip as they embroidered their funeral shrouds.

Standing with one foot in the grave ... |

|

Ed Myskowski wrote (November 13, 2012):

Douglas Cowling wrote:

< girls in Bach's time had two "hope" : one for their wedding and one for their funerals. It was a social occasion for them to gather, sing a few funeral hymns and then gossip as they embroidered their funeral shrouds. Standing with one foot in the grave ... >

As are we all! Indeed, preferable to both feet (at least for this writer). On the right side of the grass, as the Irish (Americans?) are wont to joke. |

|

Julian Mincham wrote (November 13, 2012):

Douglas Cowling wrote:

< the historically-conditioned world view of Bach towards death >

Can you explain what you mean by this Doug? |

|

William Zeitler wrote (November 13, 2012):

[To Douglas Cowling] I'm no scholar, but it seems to me we may not fully appreciate the impact the Thirty Years War must still have had in Bach's time. Estimates range from 66% to 75% of the Germanic population died-due to the war itself, famine, disease, etc. (Contrast that with WW II in which estimates range from about 10% to 20% of the population in the European theater perished.) Although the Thirty Years War ended in 1648, in Bach's day they would still be recovering from the economic and infrastructure devastation it wrought-and not enough survivors to tackle the problems? What-2/3 of Bach's children didn't make it to adulthood? Bury two and one lives? Himself an orphan at age 9? Death and the precariousness of Life would have brooded over Bach's world to an extent I'm thinking we comfy-moderns can't begin to imagine. |

|

Linda Gingrich wrote (November 13, 2012):

William Zeitler wrote:

< I'm no scholar, but it seems to me we may not fully appreciate the impact the Thirty Years War must still have had in Bach's time. >

And the impact of the Thirty Years War was not the only consideration. Death must have been ever present in a way we don't understand—women frequently died in childbirth, there were no antibiotics to fight infections, heath care was primitive at best, attitudes toward hygiene were different than now, no pain killers--living with pain must have been common, and they may have often felt fenced in by threats to life and limb. Heaven was a place of safety, bliss and joy.

We are very fortunate to live in light of the advances in medicine we experience! |

|

William Zeitler wrote (November 13, 2012):

[To Linda Gingrich] On a personal note (regarding Bach):

When I was in high school I was a reasonably developing keyboard player: maybe half the first book of the WTC, some medium-difficulty Beethoven piano sonatas, tackling my first Chopin Etude, etc. When I was 16 my youngest brother committed suicide. After all the police and paramedics left, I sat down and played Bach until sleep overtook me. In the hell that ensued I turned to playing Bach in my darkest hours. There was something about his music, light-years beyond anyone else's, that had the quality "I well know grief, but God is in His Heaven, and all will be well."

Now, as a professional composer myself (that is, for a living), I all the more appreciate the truth in Beethoven's comment "Nicht Bach, aber Meer!" (Not 'brook', but 'ocean'!). That is, beyond all the scholarship (as important and interesting as that is) there is a reason we go to all this trouble with his music.

What are the great Mysteries of Life? Love, Death, Suffering, God, Eternity? Bach fearlessly took on all of them in his art. Very few have had anywhere near the same craft and vision to do so--in any medium. |

|

Julian Mincham wrote (November 13, 2012):

William Zeitler wrote:

< After all the police and paramedics left, I sat down and played Bach until sleep overtook me. In the hell that ensued I turned to playing Bach in my darkest hours. There was something about his music, light-years beyond anyone else's, that had the quality "I well know grief, but God is in His Heaven, and all will be well." >

I know exactly what you mean. I had a similar experience when my parents died a few weeks apart. I found no music more consoling then that by Bach. |

|

Kim Patrick Clow wrote (November 14, 2012):

Linda Gingrich wrote:

<< I'm no scholar, but it seems to me we may not fully appreciate the impact the Thirty Years War must still have had in Bach's time. >>

< And the impact of the Thirty Years War was not the only consideration. Death must have been ever present in a way we don't understand—women frequently died in childbirth, there were no antibiotics to fight infections, heath care was primitive at best, attitudes toward hygiene were different than now, no pain killers--living with pain must have been common, and they may have often felt fenced in by threats to life and limb. >

And during this period, death would come just as frequently with absolutely NO regard for station in life. Queen Anne of Great Britain

(6 February 1665 – 1 August 1714) was pregnant 17 times. And none of her children lived to adolescence. Only two (I think) lived past five years of age.

And about "Bist du bei mir," this is where overly-religious Victorian era sentimentality pastes a veneer on music that never existed. The original tune was a love song from Gottfried Heinrich Stölzel's opera Diomedes, about the Trojan war hero. And its inclusion in the Notebook for Anna Magdalena Bach was no doubt understood as a love song between the composer and his wife. So its use as a wedding piece makes perfect sense, to me anyway. |

|

Ed Myskowski wrote (November 14, 2012):

William Zeitler wrote:

< I all the more appreciate the truth in Beethoven's comment "Nicht Bach, aber Meer!" (Not 'brook', but 'ocean'!). >

Thanks for passing this along, new to me. |

| |

|

Bach Cantatas reflecting the current pandemic of coronavirus disease |

|

Aryeh Oron wrote (March 28, 2020):

BWV 25: https://www.bach-cantatas.com/BWV25.htm

Mvt. 2: Recitative:

Die ganze Welt ist nur ein Hospital,

Wo Menschen von unzählbar großer Zahl

Und auch die Kinder in der Wiegen

An Krankheit hart darniederliegen.

English:

The whole world is nothing but a hospital

where in numbers too great to count people

and even children in their cradles

lie down in pain and sickness.

BWV 48: https://www.bach-cantatas.com/BWV48.htm

Mvt. 2: Recitative

O Schmerz, o Elend, so mich trifft,

Indem der Sünden Gift

Bei mir in Brust und Adern wütet:

Die Welt wird mir ein Siech- und Sterbehaus,

Der Leib muss seine Plagen

Bis zu dem Grabe mit sich tragen.

English:

O pain, O misery, that strikes me,

while the poison of sin

rages in my breast and veins:

the world becomes for me a house of sickness and death,

the body must bear its troubles

with it until the grave.:

The music of Bach has always been a comfort for the soul, especially in such hard times for the mankind.

I wish you all good health. |

|

Julian Mincham wrote (March 28, 2020):

[To Aryeh Oron] Yes it is extraordinary how much of the events of one's life can be found reflected in the cantatas. May I add to the theme by referencing BWV 156, a unique cantata (without any choruses) which reflects the moments of hovering between life and death as the 'sick body slumps.' Beginning with a sinfonia (known to most as the slow movement of the keyboard concerto in F minor) the second movement (duet) is unlike any other movement in the canon as it pictures time standing still as the soul hovers between life and death. On the surface, a depressing theme--but, as we know, Bach never leaves us completely without hope as the last two movements demonstrate.

For those who wish to follow up and hear this cantata (again?) I copy the notes on the duet taken from my cantata website.

This is an extraordinary movement, in character like no other in the canon. It is a duet, the soprano intoning the six phrases of a chorale melody around which the tenor weaves his own line. From his earliest attempts of composing music for the church, Bach had shown interest in combining chorales with arias as well as with choruses, and it seems that in these later works his interest was re-kindled. Certainly, and if this aria is anything by which to judge, he must have realised that such possibilities of experiment and artistic ihad by no means been exhausted.

The chorale by Schein (Dürr p 213) is not that which concludes the cantata. It will, however, be known to those familiar with the St John Passion where it appears in part 2. Here its text is that of a simple prayer—-deal with me, oh God, as Your generosity allows—-do not refuse to aid me but accept my soul when it departs from this world. It ends with the quasi-Shakespearean phrase ′All′s well that ends well!′

The words sung by the tenor, however, are concerned more specifically with the imminent arrival of death itself—-I stand, one foot within the grave, my sick body decaying—-Come and bless my demise, I have now set my house in order. It is from the images evoked by these lines that the main musical building blocks for this strange movement seem to have been derived.

The upper strings unite (the violas contributing a particularly distinctive doleful sound quality to the violins) to play the one obbligato melody. It begins on a long, sustained note of f, presumably suggesting the inactivity of standing motionless at the graveside. The descending continuo line against it depicts the imagined act of being lowered into the grave, but its syncopated notes make it quite impossible to detect the rhythmic structure of the piece without recourse to the score. Time stands still, or perhaps it has no further meaning for man as he stands at the very brink of death.

http://www.jsbachcantatas.com/user_files/file/aa-vol-3-sound-midifiles/aa156-1.mid |

|

|

|

In bar 4 the continuo introduces a new idea incorporating a little run of falling semi-quavers, immediately taken up by the upper strings and repeated sequentially, the direction of which is also downwards. Just four bars before the tenor entry the clouds suddenly darken, minor-mode colourings in the harmony unexpectedly touching upon Cm, a key not even related to that of the movement! In fact, this partially explains why Bach chose to set a piece dealing with death and sickness in a major key. He wanted to use the contrasts between the established major and the darker minor to act as metaphors for these ominous events. This tonal dichotomy continues to assert itself throughout the movement.

http://www.jsbachcantatas.com/user_files/file/aa-vol-3-sound-midifiles/aa156-2.mid |

|

|

|

The dark sound of the low writing of the upper strings, never aspiring to extend above the treble stave, colours the movement from start to finish.

The tenor line is largely derived from the material of the continuo theme but still contains many delicious moments of particular emphasis e.g. the tortuous writhings of the decaying body (bars 32-6), the declamatory—-Come dearest God—-(bars 40-42) and the latter emphasis upon selig—-blessed [as we request our ending to be].

This is a haunting movement, powerfully conveying those moments approaching death. Once heard, it is not quickly forgotten. |

|

Paul Beckman wrote (March 28, 2020):

[To Julian Mincham] And then there's BWV 101, "Nimm von uns, Herr du treuer Gott."

CH: Take away from us, Lord, faithful God,

the heavy punishment and great suffering,

which we, with countless sins

have too much deserved.

Protect us against war and precarious times,

against plagues, fire, and great misery.

(Translation from Emmanuel Music, http://www.emmanuelmusic.org/notes_translations/translations_cantata/t_bwv101.htm) |

|

Julian Mincham wrote (March 28, 2020):

BWV 101 opens with one of the greatest, and most original chorale choruses we are ever likely to hear! |

| |

|

Death in Bach's Vocal Works: Discussions | Article: 'Death' in Bach's sacred libretti [by Thomas Braatz] |

|

General Topics:

Main Page

| About the Bach Cantatas Website

| Cantatas & Other Vocal Works

| Scores & Composition, Parodies, Reconstructions, Transcriptions

| Texts, Translations, Languages

| Instruments, Voices, Choirs

| Performance Practice

| Radio, Concerts, Festivals, Recordings

| Life of Bach, Bach & Other Composers

| Mailing Lists, Members, Contributors

| Various Topics

|

|

|