|

|

Cantata BWV 42

Am Abend aber desselbigen Sabbatas

Discussions - Part 4 |

|

Continue from Part 3 |

|

Discussions in the Week of August 22, 2010 (3rd round) |

|

Douglas Cowling wrote (August 21, 2010):

Week of August 22, 2010: ³Am Abend aber desselbigen Sabbats², BWV 42

Week of August 22, 2010:

³Am Abend aber desselbigen Sabbats², BWV 42

Cantata for the First Sunday After Easter (Quasimodogeniti)

Introit: ³Quasimodo geniti²

Motet: ³Christus Resurgens²

³Jam Non Dicam²

³Tres Sunt ³

Hymn de Tempore: ³Christ Lag in Todesbanden²

Pulpit Hymn: ³Christ ist Erstanden²

Hymns for Chancel, Communion & Closing:

³Erscheinen ist der Herrlichen Tag²

Performance History: Easter 1725

Friday, March 30: Good Friday

St. John Passion, BWV 245 2nd version: 1st performance

Sunday, April 1: Easter Day (1st Day of Easter)

Easter Oratorio, BWV 245 1st performance

³Christ Lag in Todesbanden², BWV 4 3rd performance

Monday, April 2: Easter Monday (2nd Day of Easter)

³Bleib Bei Uns², BWV 6 1st performance

Tuesday, April 3: Easter Tuesday (3rd day of Easter)

Unknown

Sunday, April 8, First Sunday after Easter (Quasimodogeniti)

³²Am Abend Aber², BWV 42 1st performance

Is there any scholarly speculation about the missing cantata for Easter Tuesday? As in 1724, the number of premieres in one 10-day period is prodigious.

Later performances:

2nd performance: April 1, 1731- Leipzig

3rd performance: c. 1742 - Leipzig

Has anyone crunched the numbers of how long Bach waited before reviving a cantata? Once a decade seems an average, yet BWV 4 appears to have been a perennial favourite, having been performed the previous year probably as a communion cantata. Stiller has a long list of cantatas which he speculates could have been repeated as ³sub communione² cantatas. Is there any evidence that Bach revived a cantata without revising it?

* BCML page: (texts, translations, scores and readings): http://www.bach-cantatas.com/BWV42.htm

* Live streaming: http://www.bach-cantatas.com/Mus/BWV42-Mus.htm

* Commentary (Mincham): http://www.jsbachcantatas.com/documents/chapter-42-bwv-4--42.htm

* Previous Discussions: http://www.bach-cantatas.com/BWV42-D.htm

* Provenance (Braatz): http://www.bach-cantatas.com/BWV42-D2.htm

The second series of discussions introduced some valuable primary material on the provenance of the cantata¹s manuscripts. Caveat lector: The conclusions drawn from the material about the compositional, copying and rehearsal schedules of the cantata were the subject of considerable controversy.

* Notes on Movements:

Mvt. 1: Sinfonia

The ³purpose² of the opening sinfonia eludes most analysis, although we can safely exclude Schweitzeresque programmatic retrojections (e.g. the wind trio refers to the ³two or three² from the dictum in the alto aria) or the

Exhausted Choir Hypothesis. Bach may simply have wanted the ³weight² provided by an overture during the festive Easter season while retaining the intimate atmosphere of the alto aria.

It is worth noting that the virtuoso bassoon part is remarkably independent: it rarely plays in the tutti ritornello with the bass and has a very high range reaching up to G above middle C. This part is so individual that it must have been intended for a specific player. Dreyfus analyzes the light ³gallant² features of the part in ³Bach¹s Continuo Group.²

Dreyfus also tackles the complicated continuo question in this cantata and concludes that both organ and harpsichord were used. There are both Cammerton and Chorton parts, both figured by Bach. The latter has a ³tacet² section for organ in the 3rd movement.

Mvt. 2: Recitative (Tenor):

³Am Abend aber desselbigen Sabbats²

The quiet throbbing figure in the continuo strings, suggestive of expectant prayer, is similar to the accompanied recitative in ³Jauchzet Gott in allen Landen.² That repeated figure may have been realized here by the harpsichord, the organ and bassoon sustaining the harmonies. Would an arpeggiated realization be appropriate? (as in the quiet opening of Handel's "Zadok the Priest")

Mvt. 3: Aria (Aria):

³Wo zwei und drei versammlet sind²

The monumental scale of this aria and the continuing independence of the bassoon part might suggest that the A section was the second movement of the concerto whose first movement opened the cantata. The contrasting B section in 12/8 is notable in that the organ part drops out, presumably leaving the harpsichord as the sole continuo instrument. Whether this is a unique occasion or whether Bach varied his continuo sound is provocative.

Mvt. 4: Aria & Chorale (Soprano & Tenor):

³Verzage nicht, o Häuflein klein²

Has anyone identified the chorale tune used in this movement? None of the commentaries mention it (Dürr?) If the movement had not been labeled ³Chorale², I would never have realized it. Dreyfus points to the paired bass line and notes that Bach may have added a violone part in later performances after the purchase of an instrument in 1732. What are the differences between the various performances?

Mvt. 5: Recitative (Bass):

³Man kann hiervon ein schön Exempel sehen²

The coda anticipates the arpgeggio figure of the succeeding aria.

Mvt. 6: Aria (Bass):

³Jesus ist ein Schild der Seinen²

The oboes fall silent in this energetic battle piece and the bassoon recedes into the continuo group with no further independent role. The cascading arpeggios and dactylic motif are similar to ³Ehre sei Gesungen²,

the opening chorus of Part 5 of the Christmas Oratorio (same key as well).

Mvt. 7: Chorale:

³Verleih uns Frieden gnädiglich²

Luther¹s hymn was a 1529 reworking of the Latin ³Da Pacem² which concluded with a prayer for rulers and good government. It was regularly sung as an acclamation for Lutheran princes, a kind of ³God Save the King.² Johann Walher wrote settings contemporary with Luther. Schütz wrote his for Dresden, and it was still a concert fixture as late as Mendelssohn. |

|

Evan Cortens wrote (August 22, 2010):

Douglas Cowling wrote:

< Has anyone crunched the numbers of how long Bach waited before reviving a cantata? Once a decade seems an average, yet BWV 4 appears to have been a perennial favourite, having been performed the previous year probably as a communion cantata. Stiller has a long list of cantatas which he speculates could have been repeated as ³sub communione² cantatas. Is there any evidence that Bach revived a cantata without revising it? >

Doug raises some interesting questions about the chronology of cantata performances during the 1725 Easter season. This post is fairly quick, and I haven't done thorough looking, but I thought it would be helpful to cite the relevant portions of Dürr's magnum opus "Zur Chronologie der Leipziger Vokalwerke J. S. Bachs", where it seems Doug's information (perhaps indirectly) originates (pp. 79-80). [Translations are my own clumsy attempts.]

1) First point, the BWV number for April 1 should be 249, just a typo there, I think.

2) Dürr says, regarding April 1st, that BWV 4 wasrevived at the Universitätskirche, not at one of the city churches (i.e., St. Thomas or St. Nikolai). He goes on to say:

Aufführung vielleich auch am 3. 4. in den Stadtkirchen, sicher jedoch an einem der beiden Tage (s. zum 3. 4.)

Performance possibly also on April 3rd in the city churches, but certainly on one of the two days (see April 3rd).

3) For April 3rd, Dürr offers the following:

Aufführung nicht nachweisbar. Vielleich jedoch Aufführung der Kantate 4 (vgl. oben zum 1. 4.).

No performance detectable. Possibly a performance of Cantata BWV 4 (see above).

---

Perhaps this helps to clarify some things. If only Bach had written some dates down, or kept a calendar of some sort. As it stands, reperformances are only detectable if some datable invention has been made in the score and/or the parts for that occasion. That is to say, any one of a number of appropriate cantatas could well have been performed on April 3rd, 1725, but if Bach (or a copyist) didn't add an instrument, replace a part, revise something, etc, there is virtually no way to tell.

One of the most interesting bits of research being done right now is by scholars who are digging through German (and, believe it or not, Russian) libraries, finding various eighteenth-century materials. During Bach's time in Leipzig (and before and after) batches of text booklets were printed, giving the text for the cantatas for the next few weeks. These booklets all have years as well. These of course are perhaps the clearest indications of a work's performance. In some cases they do survive (a collection of facsimiles edited by Martin Petzoldt is available) but in most cases they do not. Fingers crossed more keep turning up though! |

|

Kim Patrick Clow wrote (August 23, 2010):

Douglas Cowling wrote:

< Given Bach's innate encyclopedism (sic), he must have kept a journal or index of his works which recorded when they were composed and when they were revived,

How was it organized?

By year - like a diary?

By Sunday - like a hymn book?

By title - like a library catalogue?

The Orgelbüchlein shows one schema which was common among all Lutheran composers:

Advent

Christmas

New Year

Purification

Lent

Easter

Pentecost

Catechism

Miscellaneous

This is roughly the practical sequence which structured Bach's working calendar. The interesting thing about the collection, of course, is that Bach only completed 46 out of a projected 164 chorale-preludes. Thus, the collection is both a record of completed works and a prospectus of future works, all contained within the sequence which shaped all performance, academic and ecclesiastical rosters and records.

Did Bach's "Missing Catalogue" record not only performances but works in progress? Are there any comparable catalogues from contemporary composers? Is Mozart's personal works journal part of this tradition? >

I don't know of any thematic index kept by any baroque composers, but of course doesn't mean they didn't, they could have been thrown out or lost over the years. But why did composers in the later 18th century start doing cataloguing their own music? Several of the music courts would draw up inventories of their music libraries, usually after a Kapellmeister died ( this happened with Fasch, Stölzel, Graupner, etc). They can be frustrating documents, since some only use broad generalizations (e.g. Zerbst listed 80 Vivaldi concerti-- but how many were unique No incipits are listed, so there's no way of knowing Fasch worked in Prague for the same noble family that The Four Seasons were dedicated to, so it would seem logical to assume some of them were unique sources). |

|

Evan Cortens wrote (August 23, 2010):

Douglas Cowling wrote:

< Given Bach's innate encyclopedism (sic), he must have kept a journal or index of his works which recorded when they were composed and when they were revived, >

Certainly it's true that Bach had a very good sense of what music he'd written and what sort of shape it was in, or else he wouldn't be able to dig back into his catalogue (if you will) and pull things out for revision so often. BWV 4 has already been mentioned, but there's also of course the B Minor Mass (though it's hard to call this simply a revision of a pre-existing work), the 'great 18 chorales' and on and on. Whether or not he ever kept a written record during his lifetime is of course unknown, but there doesn't seem to be any evidence of it. Then again, would there be?

Off the top of my head, the phenomenon Kim mentions seems to be the more common. Upon a composer's death, an inventory of his estate is prepared. This happened not just with the composers Kim mentions, but also with J. S. and C.P.E. Bach. The catalogue of the former's works were published as part of his obituary in (I believe?) 1754. C.P.E. Bach, however, clearly began preparing his catalogue before his death. In fact, it contains not just a full listing of all of his own compositions, but also those of other composers in his possession, and his (extensive!) portrait collection. It seems to have been prepared with the aid of his daughter, Anna Carolina Philippina, who also assisted in the day-to-day running of the cantorate in the 1780s. This catalogue was eventually published in 1790, two years after C.P.E.'s death, and seems to have circulated fairly widely; a number of copies are extant now, and a facsimile of Westphal's catalogue has been published in facsimile form, edited by Rachel Wade.

Mozart, and I must add Haydn, are the only two eighteenth-century composers that I can think of off the top of my head who prepared catalogues of their works during their lifetimes. These catalogues would eventually form the basis for the later thematic catalogues prepared, respectively, by Köchel and Hoboken. |

|

Douglas Cowling wrote (August 23, 2010):

Evan Cortens wrote:

< The catalogue of the former's works were published as part of his obituary in (I believe?) 1754. C.P.E. Bach, however, clearly began preparing his catalogue before his death. >

Wolff suggests that Bach began the divison of his musical estate before his death, dividing his library among his sons, and commissioning copies of works for which he wanted multiples. A catalogue of his own making would have made the process much easier. |

|

William L. Hoffman wrote (August 23, 2010):

Picking up on Evan Cortens' post, CPE Bach's Estate Catalog includes pages of listings of his father's work in manuscript, showing the sacred cantatas by yearly services, beginning with the First Sunday in Advent and usually listing all incipts by cycles 1, 2, and 3. Gerhard Herz suggested many years ago that Bach stored his church year cantatas by service in shelves with dividers for each service in his resident work office, each work score and parts bundled. These Bach could readily access for reperformances. This format is shown in CPE's accounting as well as the Obituary which lists basic genre in the same fashion. Christoph Wolff also suggests that Bach himself made the designation of the estate division in his final months, including the alternate distribution of scores and parts sets. The actual physical distribution was done probably by Friedemann, based on Dad's general directions, and in most cases he basically examined the incipit of each bundle. Friedemann, or whomever, made a few mistakes with the chorale cantatas by incipit while the von Ziegler works were correctly placed in the third cycle distribtuion. Naturally, I defer to Thomas Braatz for any clarification or correction. |

|

Kim Patrick Clow wrote (August 23, 2010):

Douglas Cowling wrote:

< Handel sold his music from a room in his Brooks Street house (where the book shop is today!). Did he have a products listing to consult? >

I would guess he would just offer potential customers specific pieces he knew he had copies, or would allow them to inspect a stack of manuscripts he had already prepared. Telemann would print ads in Hamburg, listing specific items he was promoting. |

|

Evan Cortens wrote (August 23, 2010):

Douglas Cowling wrote:

< Wolff suggests that Bach began the divison of his musical estate before his death, dividing his library among his sons, and commissioning copies of works for which he wanted multiples. A catalogue of his own making would have made the process much easier. >

William L. Hoffman wrote:

< Christoph Wolff also suggests that Bach himself made the designation of the estate division in his final months, including the alternate distribution of scores and parts sets. >

I wonder, where does Wolff say this? The division of Bach's estate has always been a special interest of mine. I'd be interested to see what evidence he gives.

Douglas Cowling wrote:

< Handel sold his music from a room in his Brooks Street house (where the book shop is today!). Did he have a products listing to consult? >

In London, the commercial music scene was much more highly developed than on the continent. It seems that publishers regularly advertised their latest offerings. Whether there were full catalogues of their offerings though, I'd be surprised. If only because they often didn't keep the original plates around for very much longer than the initial print run. Customers weren't often in the market for "old" music, so it didn't make sense to keep plates around longer than a few months.

William L. Hoffman wrote:

< Picking up on Evan Cortens' post, CPE Bach's Estate Catalog includes pages of listings of his father's work in manuscript, showing the sacred cantatas by yearly services, beginning with the First Sunday in Advent and usually listing all incipts by cycles 1, 2, and 3. Gerhard Herz suggested many years ago that Bach stored his church year cantatas by service in shelves with dividers for each service in his resident work office, each work score and parts bundled. >

There is one possible snag in this argument though, namely that C.P.E. Bach went through all of his father's music and prepared the title wrappers, listing the title and instrumentation of the work. (In fact, to keep things a little bit on topic at least, this is the case for the autograph score of BWV 42.) This suggests to me that C.P.E. may well have gone through and entirely reorganized his musical inheritance, or at least that this is a possibility. |

|

Kim Patrick Clow wrote (August 23, 2010):

Evan Cortens wrote:

< Mozart, and I must add Haydn, are the only two eighteenth-century composers that I can think of off the top of my head who prepared catalogues of their works during their lifetimes. These catalogues would eventually form the basis for the later thematic catalogues prepared, respectively, by Köchel and Hoboken. >

After mulling it over a bit, I know Haydn prepared his thematic index quite late in his life. I *think* some of the rationale was the confusion over many pirated composers works sold as Haydn compositions (e.g. there was a huge industry in Paris of selling other composers' symphonies as Haydn's). There was relatively little Mozart published during his lifetime, so I have no idea what his motivation was. |

|

Douglas Cowling wrote (August 23, 2010):

Evan Cortens wrote:

< I wonder, where does Wolff say this? >

Bach: The Learned Musician, p. 457-465 |

|

Ed Myskowski wrote (August 23, 2010):

Evan Cortens wrote:

< I wonder, where does Wolff say this? The division of Bach's estate has always been a special interest of mine. I'd be interested to see what evidence he gives. >

Doug subsequently provides the reference.

[from Will(?), lost in translation]

>> Gerhard Herz suggested many years ago that Bach stored his church year cantatas by service in shelves with dividers for each service in his resident work office, each work score and parts bundled. <<

Perhaps related to Dougs citation from Wolff: JSB:TLM?

< There is one possible snag in this argument though, namely that C.P.E. Bach went through all of his father's music and prepared the title wrappers, listing the title and instrumentation of the work. (In fact, to keep things a little bit on topic at least, this is the case for the autograph score of BWV 42.) This suggests to me that C.P.E. may well have gone through and entirely reorganized his musical inheritance, or at least that this is a possibility. >

I believe the original argument was whether (or not) JSBach stored his church year cantatas by service. Even without objective evidence, this seems to be a given (or at least reasonable presumption), considering reperformance/revision chronology.

Note that whatever CPE Bach may have done subsequently does not contradict (or support) whatever JSBachs organization methods may have been. I suspect the organization methods were admirable. Perhaps his wives and daughters were involved? |

|

Evan Cortens wrote (August 23, 2010):

[To Ed Myskowski] Agreed! I certainly think that it makes most sense for J. S. Bach to store his cantatas in this way. My only point was, with respect to Herz's argument, that I don't think we can tell how JSB organized anything by looking at the way CPEB subsequently organized it. In other words, I agree exactly with Ed, CPEB's organization "does not contradict (or support)" JSB's organization. |

|

Douglas Cowling wrote (August 23, 2010):

Evan Cortens wrote:

< I don't think we can tell how JSB organized anything by looking at the way CPEB subsequently organized it. >

I always get a sick feeling when I read that Bach's study was demolished during renovations to the Thomasschule in the 1890s -- long after his reputation had been restored and celebrated. |

|

Douglas Cowling wrote (August 29, 2010):

William L. Hoffman wrote:

< Versage nicht, O Häuflein <Stiller 240: Dresden E3>, 42/4(S.1) E;1 O Little Flock, Fear Not the Foe; with the Fabricus text became a marching song of King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden. >

Is the tune online somewhere? |

|

Julian Mincham wrote (August 29, 2010):

Hymn

[To Douglas Cowling] There seems to be some scholastic confusion about this Hymn. Dürr, in something of a red herring I think, associates it with Kommther zu mir, spricht Gottes Sohn (which may be located in the Bach

Riemenscheider 371 chorale collection). But I don't think this is the case.

Boyd mentions the hymn by Jacob Fabricus.

A quick google (shock, horror!!) turned up the information I have pasted below bu no copy of the music.if anyone does have a version of it I too would like to see it.

By the way this movement under discussion is a really stunning duet. Apparently Bach put the phrasing of the bass line in himslef thus ensuring that the tensions between 6/8 and 3/4 would be obvious in performance.

Texts by this person.People › Altenburg, Michael, 1584-1640 › Tunes Altenburg, Johann Michael, b. at Alach, near Erfurt, on Trinity Sunday, 1584. After completing his studies he was for some time teacher and precentor in Erfurt. In 1608 he was appointed pastor of Ilversgehofen and Marbach near Erfurt; in 1611, of Troch-telborn; and in 1621 of Gross-Sommern or Som-merda near Erfurt. In the troublous war times he was forced, in 1631, to flee to Erfurt, and t, on the news of the victory of Leipzig, Sept. 17, 1631, he composed his best known hymn. He remained in Erfurt without a charge till, in 1637, he was appointed diaconus of the Augustino Church, and, in 1638, pastor of St. Andrew's Church. He d. at Erfurt February 12, 1640 (Koch, iii. 115-117 ; Allg. Deutsche Biog., i. p. 363, and x. p. 766—the latter saying he did not go to Erfurt till 1637). He was a good musician, and seems to have been the composer of the melodies rather than of the words of some of the hymns ascribed to him. Two of his hymns have been tr. into English,

viz. :—

1. Aus Jakob's Staxnm ein Stern sehr klar. [Christmas.]

Included as No. 3 of his Christ-liche liebliche und anddchtige newe Kirchen- und Hauss-Gestinge, pt. i., Erfurt, 1G20, in 3 st. of 5 1. According to Wetzel's A. H., vol. i., pt. v. p. 41, it was first pub. in J. Forster's Jlohen Festtags-Schreinlein, 1611. In the Unv. L. S., 1851, No. 24. It has been tr. as " From Jacob's root, a star so

clear," by Miss Manington, 1864, p. 13.

2. Verzage nicht du Hauflein klein. [In Trouble.] Concerning the authorship of this hymn there are three main theories—i. that it is by Gustavus Adolphus; ii. that the ideas are his and the diction that of his chaplain, Dr. Jacob Fabricius; and iii. that it is by Altenburg. In tracing out the hymn we find that:—

The oldest accessible form is in two pamphlets published shortly after the death of Gustavus Adolphus, viz., the Epicedion, Leipzig, n.d. but probably in the end of 1632 [Royal Library, Berlin]: and Arnold Mengering's Blutige Siegs-Crone, Leipzig, 1633 [Town Library, Hamburg]. In the Epicedion the hymn is entitled, "Konig-licher Schwanengesang So ihre Majest. vor dem Ltltzen-schen Treffen inniglichen zu Gott gesungen "; and in the Siegs-Crone, p. 13, "Der S. Kon. Mayt. zu Schweden Lied, welches Sie vor der Schlacht gesungen." In both cases there are 3 sts.

:—

i. Verzage nicht, du Hiiuffiein klein. ii. Triistedich dess, dass deine Sach. iii. So wahr Gott Gott ist, und sein Wort.

The next form is that in J. Clauder's Psalmodiae Novae Pars Tertia, Leipzig, 1636, No. 17, in 5 st. of 6 lines, st. i.-iii. as above, and—

iv. Ach Gott gieb in des deine Gnad v. Hilff dass wir auch nach deinem Wort.

No author's name is given. In the Bayreuth G. B., 1668, p. 266, st. iv., v., are marked as an addition by Dr. Samuel Zehner; and by J. C. Olearius in his Lieder-Schatz, 1705, p. 141, as written in 1638 (1633 ?), when the Croats had partially burnt Schleusiugen, where Zehner was then superintendent.The third form of importance is that given in Jcremias Weber's Leipzig G. B., 1638, p. 651, where it is entitled " A soul-rejoicing hymn of Consolation upon the watchword—God with us—used by the Evangelical army in the battle of Leipzig, 7th Sept., 1631, composed by M. Johann Altenburg, pastor at Gross Soinmern in Dtiringen," [i.e. Sommerda in Thuringia]. It is in 5 sts., of which sts. i.-iii. are the same as the 1633, and are marked as by Altenburg. St. iv., v., beginning—

iv. Drilmb sey getrost du kleines Heer v. Amen, das hilff Ilerr Jesu Christ,

are marked as " Additamentum Ignoti." This is the form in C. U. as in the Berlin G. L. S., ed. 1863, No. 1242.In favour of Altenburg there is the explicit declaration of the Leipzig G. B., 1638, followed by most subsequent writers. The idea that the hymn was by Gustavus Adolphus seems to have no other foundation than that in many of the old hymn-books it was called Gustavus Adolphus's Battle Hymn. The theory that the ideas were communicated by the King to his chaplain, Dr. Fabricius, after the battle of Leipzig, and by Fabricius versified, is maintained by Mohnike in his Hymnologische Forschungen, 1832, pt. ii. pp. 55-98, but rests on very slender evidence. In Koch, viii. 138-141, there is the following striking word-picture:—If, then, we must deny to the hymn Albert Knapp's characterisation of it as " a little feather from the eagle wing of Gustavus Adolphus," so much the more its original title as his "Swan Song" remains true. It was on the morning of the 6 Nov., 1632, that the Catholic army under Wallenstein and the Evangelical under Gustavus Adolphus stood over against each other at Lutzen ready to strike. As the morning dawned Gustavus Adolphus summoned his Court preacher Fabricius, and commanded him, as also the army chaplains of all the other regiments, to hold a service of prayer.

During this service the whole host sung the pious king's battle hymn—

" Verzage nicht, du Hauflein klein."

He himself was on his knees and prayed fervently. Meantime a thick mist had descended, which hid the fatal field so that nothing could be distinguished. When the host had now been set in battle array he gave them as watchword for the fight the saying, "God with us," mounted his horse, drew his sword, and rode along the lines of the army to encourage the soldiers for the battle. First, however, he commanded the tunes Ein feste Burg and Es wollt tins Gott genadig sein to be played by the kettledrums and trumpets, and the soldiers joined as with one

voice. The mist now began to disappear, and the sun shone through. Then, after a short prayer, he cried out: " Now will we set to, please God," and immediately after, very loud, " Jesu, Jesu, Jesu, help me today to fight for the honour of Thy Holy Name." Then he attacked the enemy at full speed, defended only by a leathern gorget. " God is my harness," he had said to the servant who wished to put on his armour. The conflict was hot and bloody. About 11 o'clock in the forenoon the fatal bullet struck him, and he sank, dying, from his horse, with the

words, “My God, my God!" Till twilight came on the fight raged, and was doubtful. But at length the Evangelical host obtained the victory, as it had prophetically sung at dawn."

This hymn has ever been a favourite in Germany, was sung in the house of P. J. Spener every Sunday afternoon, and of late years has been greatly used at meetings of the Gustavus Adolphus Union—an association for the help of Protestant Churches in Roman Catholic countries. In translations it has passed into many English and American collections.

Translations in C. U.:—

1.Fear not, 0 little flock, the foe. A good tr. from the text of 1638, omitting st. iv., by Miss Winkworth, in her Lyra Ger., 1855, p. 17. Included, in England in Kennedy, 1863, Snepp's S. of G. and G., 1871, Free Church H. Bk., 1882, and others; and in America in the Sabbath H. Book., 1858, Pennsylvania Luth. Ch. Bk., 1868, Hys. of the Church, 1869, Bapt. H. Bk., 1871, H. and Songs of Praise, 1874, and many others.

1.Be not dismay'd, thou little flock. A good tr. of st. i.-iii. of the 1638 text in Mrs. Charles's V. of Christian Life in Song, 1858, p. 248. She tr. from the Swedish, which, in the Swensha Psalm Boken, Carlstadt, N.D. (1866), is given as No. 378, "Forfaras ej, du lilla hop !" and marked Gustaf II. Adolf. Her version is No. 204 in Wilson's Service of Praise, 1865.

1.Thou little flock, be not afraid. A tr. of st. i.-iii. from the 1638 text, by M. Loy, in the Ohio Luth. Hymnal, 1880, No. 197.Other trs. are all from the text of 1638.(1.) " Be not dishearten'd, little flock," by Dr. II. Mills, 1856, p. 121. (2.) " Despond not, little band, although," by Dr. G. Walker, 1860, p. 41. (3.) "Be not dismay'd, thou little flock, Nor," by E. Massie, 1866, p. 143. (4.) " 0 little flock, be not afraid," in J. D. Burns's Memoir and Remains, 1869. p. 226.

–John Julian, Dictionary of Hymnology (1907) |

|

Russell Telfer wrote (August 29, 2010):

Julian Mincham wrote:

< There seems to be some scholastic confusion about this Hymn. Dürr, in something of a red herring I think, associates it with Kommther zu mir, spricht Gottes Sohn (which may be located in thBach Riemenscheider 371 chorale collection). But I don't think this is the case. >

I may have interpreted your post incorrectly, but I can at least say that Kommther zu mir, spricht Gottes Sohn is located in the Riemenscheider collection, on pages 11 and 90 to be precise. |

|

Julian Mincham wrote (August 29, 2010):

[To Russell Taelfer] Thanks Russell

I wrote carelessly. What I meant was that the hymn is a part of that collection but I don't think that what Dürr says is the case. (At least I can't see the connections with that hymn in the cantata duet).

Thanks for clarifying |

|

Douglas Cowling wrote (August 29, 2010):

Julian Mincham wrote:

< By the way this movement under discussion is a really stunning duet. Apparently Bach put the phrasing of the bass line in himslef thus ensuring that the tensions between 6/8 and 3/4 would be obvious in performance >

It is so unlike other chorale-duets where one voice has the chorale melody and the other has the free thematic material. It all looks freely-composed to me. I just don't see the shape of a chorale melody. |

|

William L. Hoffman wrote (August 30, 2010):

Douglas Cowling wrote:

< Is the tune online somewhere? >

Can't find it. |

|

Richard Mix wrote (September 2, 2010):

Verzage nicht, O Häuflein klein

William L. Hoffman wrote:

< Can't find it. >

The tune associated with Verzage nicht, O Häuflein klein is also known (and posted at Bachcantatas.com) as Kommt her zu mir. |

|

Elizabeth Schwimmer wrote (September 2, 2010):

[To Richard Mix] I posted it a couple of days ago in youtube.

Here is the link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vGkr-d4-xVE |

|

William L. Hoffman wrote (September 3, 2010):

[To Richard Mix] From Dürr JSB Cantatas 297, go to Whittaker Cantatas of JSB I:298, ref. Terry (Bach's chorales). |

|

William L. Hoffman wrote (September 15, 2010):

William L. Hoffman wrote:

< Can't find it. >

Lutheran Book of Worship (1978, Inter-Lutheran Commission on Worship), Hymn No. 361, "Do Not Despair, O Little Flock"; text, Johann M. Altenberg, 1584-1630 (four stanzas); tune, "Kommt her zu mir," Nuernberg, 1534. I can't find the C.S. Terry reference, cited in Whittaker I:298: htttp//www.oll.libertyfund.org/index.php?option=com.

Previous two and succeeding Lutheran hymnals do not have this hymn. |

|

Douglas Cowling wrote (September 15, 2010):

William L. Hoffman wrote:

< "Do Not Despair, O Little Flock"; text, Johann M. Altenberg, 1584-1630 (four stanzas); tune, "Kommt her zu mir," Nuernberg, 1534. >

I don't see any relationship between Bach's music and the tune "Kommt her zu mir". His usual pattern is to have one voice sing the chorale tune fairly straight while the second voice provides free complementary melodies. In this duet, both voices explore the same melodies and there is no superimposed chorale tune.

I would suggest that the "chorale" citation refers to the text and that the music has no relationship to the hymn tune. I would be grateful if someone could show that there is a chorale hidden in the melodic figures of the duet. |

|

William L. Hoffman wrote (September 15, 2010):

[To Douglas Cowling] The best I can do is quote the relevant passage in Whittaker I:298. "iv is headed Chorale. Duetto., but there is no hymn-melody. The words are stanza 1 of J.M. Altenburg's(?) 'Verzage nicht, o Hauflein klein' (1632), and Terry points out that this is a solitary instance of separation of hymn-stanza from its tune, and thinks that 'the melody' (the anonymous 'Kommt her zu mir, spricht Gottes Sohn' (1530) 'seems to be implied and its closing cadence is introduced.'"

This Easter Season melody, 'Kommt her zu mir," seems entirely appropriate as Bach soon after uses the associated text to a different tune on Easter 4/Cantate, Cantata 108/6, and both tune and text in Cantata BWV 74/8 for Pentecost, both with libretti of Mariane von Ziegler. |

|

Douglas Cowling wrote (September 16, 2010):

William L. Hoffman wrote:

< The best I can do is quote the relevant passage in Whittaker I:298. "iv is headed Chorale. Duetto., but there is no hymn-melody. The words are stanza 1 of J.M. Altenburg's(?) 'Verzage nicht, o Hauflein klein' (1632), and Terry points out that this is a solitary instance of separation of hymn-stanza from ts tune, and thinks that 'the melody' (the anonymous 'Kommt her zu mir, spricht Gottes Sohn' (1530) 'seems to be implied and its closing cadence is introduced.'" >

I think this makes sense, although the music's cadential figure is so conventional that it is hard to connect it with the chorale melody.

I'm wondering if the title "chorale" was originally the title given by the librettist who assumed that the music would have a straightforward chorale at this point to balance the first three movements. However, Bach decided to set the text as free concerted music and added "Duetto" to the librettist's title.

Are there any other examples of Bach changing the genre/type of a libretto's movement when he came to write the music? |

| |

|

BWV 42 |

|

Harry Fisher wrote (May 1, 2011):

[To Aryeh Oron] There is an interesting issue on your page on BWV 42, where you discuss the alto aria:

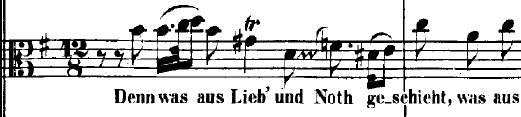

"Mvt. 3 Aria for Alto

"Her text begins with Matthew 18: 20, which has nothing to do with the Gospel for the day, yet continues the idea of Jesus' return to His believers. This Aria is long and slow moving despite the full orchestral accompaniment: "Wo zwei und drei versammelt sind / In Jesu teurem Namen, / Da stellt sich Jesus mitten ein / Und spricht dazu das Amen. / Denn was aus Lieb' und Not geschieht, / Das bricht des Hochsten Ordnung nicht". (Where two and three are gathered / In Jesus' dear Name, / There Jesus puts Himself in their midst / And speaks thereto the Amen. / For what happens out of love and need, / That does not break the Highest's decree.)"

Indeed, that's what it seems the sheet music says as well: |

|

|

|

However, on your German text page it says: |

|

|

|

What complicates matters is that Julia Hamari sings "geschicht" and Maureen Forrester "geschieht."

So, is there a "right" version? Is there perhaps an archaic usage here? Perhaps one of your German correspondents could shed som light on this.

Other than that, I like the bounce that Rilling gives the aria, almost to where it's a dance. On the other hand, there is the incomparable Maureen Forrester and her power at the deep end. Something here to love for everyone.

Thanks. |

| |

|

Continue on Part 5 |

|

|