|

|

General Topics:

Main Page

| About the Bach Cantatas Website

| Cantatas & Other Vocal Works

| Scores & Composition, Parodies, Reconstructions, Transcriptions

| Texts, Translations, Languages

| Instruments, Voices, Choirs

| Performance Practice

| Radio, Concerts, Festivals, Recordings

| Life of Bach, Bach & Other Composers

| Mailing Lists, Members, Contributors

| Various Topics

|

|

Chiasm in Bach's Vocal Works

|

|

Chiasm

Chiasm in the Choral Works of Bach |

|

Raymond Joly wrote (April 3, 2006):

Ed Myskowski wrote (April 3, 2006):

< A few additional comments on BWV 134: the cross reference was informative:

Peter Smaill wrote (December 29, 2005) re BWV 63:

the symmetry being even more obvious than BWV 4 or the SJP (BWV 245), the chiastic arrangement of:

Chorus, accompagnato recit, Duet, recit secco, Duet, accompagnato recit, Chorus.

being a palindrome based round the central word "gnaden" ("mercy"), which is contrived to lie right in the middle of a seven-line recitative, BWV 63/4.

In Dec. 2005, Douglas Cowling also responded to this post. I am a bit fuzzy on the exact courtesies to acknowledge these previous posts. I am also a bit fuzzy whether courtesy is an operative concept anymore. I am not ready to concede, just yet.

First of all, chiastic was a new word for me. As I understand it, the origin is the Greek letter chi, and in general, it refers to x-form symmetry. In music, the meaning is less restrictive, and can refer to any palindrome symmetry. For example, the nave (arch or ship) forms discussed in recent weeks. I will use it so, unless corrections ensue. Especially if the symmetry is clear, but not so clear whether ship or arch apply. Suggested:

(1) nave is architecture, of naval origin

(2) chiastic is musical symmetry, like a palindrome

(3) arch form is chiastic, with the big emphasis, the keystone, at center.

(4) ship form (improvements invited), chiastic, biggest rocks at either end.

Julian Mincham wrote (March 28, 2006):

However, the recitatives show progressive reworking. [...]

There is doubtless a potential academic thesis here

I want to be sure that my response to Julian's suggestion for a thesis topic was not misunderstood: it is an excellent suggestion, and consistent with my earlier thought that BCW discussions easily lead to research opportunities. Apparent conflict makes the research all the more necessary. I was merely expressing (and misspelling) <leisen> (God's mercy, from the long Kyrie Eleison discussion) for all graduate students, everywhere. Think before you post: Professor (former graduate student) could be lurking. This is a public forum. >

Let us leave ships and naves alone. In order to have a chiasm, you need four elements; the fifth can remain virtual: it is the point where the arms of the X meet.

ABA is a palindrome: you can read it both ways, but it is not a chiasm. AB:BA is a chiasm, and so is of course AB:C:BA. Both are palindromes too, because they are dreadfully abstract. But Recitative-Aria-Chorus-Aria-Recitative will be a palindrome only if both your recitatives and both your recitatives are similar, which I would definitely advise against. The chiasm is fun only because you realize that you have two pairs facing each other that decided to dance a little step instead of mirroring each other blandly.

I suppose this is not the occasion to type xxx, though. |

|

Peter Smaill wrote (April 3, 2006):

[To Raymond Joly] This is great stuff for clearing a room - what is the difference between a palindrome and a chiasm! ? Normally I use conversations about litotes and zeugma (try 'em)! to have the same effect. Here goes at seeing what the distinction may be and whether its is relevant, or whether the words are pretty much synonymous in the context in which musicians and musicologists use them.

Chiasm and palindrome are closely related expressions as can be seen by punching both words into a search engine. What you seem to be saying is that chiasm, being figuratively one half ( >) of a cross ("Chi") ( X ) cannot have as few as three values, whereas palindrome can. Secondly, to observe palindrome of any quality in music, the recitatives or other component movements defining the palindrome have to be similar? or maybe identical?

Whether strictly accurate or not, the SJP (BWV 245) has been referred to as palindromic for many years even though the constituents (arias, recitatives and chorales) are not all that closely related and a few skips have to be made to prove the theory:

"BWV 4 and "Jesu Meine Freude" affords positive proof of Bach's interest in palindromic forms (i.e. those that can be read forward and backwards) that a manifestation of it in the order of movements in the St John Passion (BWV 245) cannot be ignored, even if its organisation is not precise" (Paul Steinitz).

So it appears that musical scholars have been content to use the word palindrome even when the structure is not very strictly so composed.

BWV 134 is I think you are saying too short in its symmetry to be a chiastic structure. The central elements Recit-aria-Recit are only threefold. However, the core is preceded by an aria and followed by a chorus, the integration of "Lieder" in line one of the first aria, "Sieger in the last line of the chorale, and with "Sieger" and "Lieder" in the central line (sorry to repeat that for those who have already read this analysis) suggests that the chiasm is in this wider sense extending to both the inner three movements (musical structure) and outer two (points of linguistic symmetry).

I view the declaration of the incipit in BWV 134 as lying outside the area of the palindrome/chiasm, BWV 134/2-7 acting as an exposition of the believers' reaction to the passages in Luke 24:36-47 (paraphrased in BWV 134/1) dealing with he appearance of Christ among the disciples following the Resurrection.

Conclusion; it may be that chiasm cannot be used for a short palindrome, but I can't yet find any evidence of this rule. In Bach's music both expressions are seemingly used by commentators more loosely than in language, where the illustrations can be strictly symmetrical ("Able I was ere I saw Elba"). The word "Chiastic," as distinct from palindromic, seems to be used particularly of Biblical settings, particularly in relation to the Fourth Gospel.

It is pure coincidence, but I could'nt help notice, since BWV 134 deals with the Resurrection and BWV 67 with the divinity of Christ, that one of the best words demonstrated by linguists as an example of a palindrome-in-itself is -

"deified" |

|

Thomas Shepherd wrote (April 3, 2006):

Chiasm, SJP, Easter, the 700

Peter Smaill wrote:

< It is pure coincidence, but I could'nt help notice, since BWV 134 deals with the Resurrection and BWV 67 with the divinity of Christ, that one of the best words demonstrated by linguists as an example of a palindrome-in-itself is -

"deified" >

I feel that's one for a sermon sometime!

Its fantastic news from Aryeh about the membership. Its always good to hear from Bach lovers across the world - and such a great number of topics stimulated by the cantata of the week.

I gave up listening to Bach's cantatas for Lent - I'm chomping at the bit. However all is not lost 'cos I heard a most wonderful performance of St John Passion (BWV 245) here in Manchester UK last night. No famous names or artists but wonderful playing and singing by young professionals and several students of the Royal Northern College under the direction of Chris Stokes. Fab.

I'm looking forward to the Suzuki's Easter Oratorio (BWV 249) played full blast in a couple of weeks. |

|

Raymond Joly wrote (April 3, 2006):

[To Peter Smaill] It looks like I have been dogmatic myself. Frightful ! |

|

Thomas Braatz wrote (April 3, 2006):

Peter Smaill wrote:

>>Whether strictly accurate or not, the SJP (BWV 245) has been referred to as palindromic for many years even though the constituents (arias, recitatives and chorales) are not all that closely related and a few skips have be made to prove the theory:

"BWV 4 and "Jesu Meine Freude" affords positive proof of Bach's interest in palindromic forms (i.e. those that can be read forward and backwards) that a manifestation of it in the order of movements in the St John Passion (BWV 245) cannot be ignored, even if its organisation is not precise" (Paul Steinitz).

So it appears that musical scholars have been content to use the word palindrome even when the structure is not very strictly so composed.<<

It may be of interest that Alfred Dürr, in his book on the SJP (BWV 245), Bärenreiter, 3rd edition 1999, (I believe that this book has been translated into English) has a chapter entitled "The Overall Form in the Various Versions of the SJP", pp. 111-125. In this chapter, Dürr himself does not use the words 'chiasm' (only once in quotes from a work by Smend) or "palindrome' and simply refers to symmetry/symetrical throughout his detailed discussions of the various theories beginning with Friedrich Smend ("Herzstück, chiastisch") in the BJ 1926, from there to Hans Joachim Moser (BJ 1932) with his theory about the ordering of the keys/tonalities, followed by Dieter Weiss (1970 in "Musik und Kirche" who builds on Moser's theory, and finally to Eric Chafe (1981) also on the arrangement of tonalities, but with a new twist: the movement from flat to sharp keys with the all-important 'Herzstück' in a sharp key ('sharp' in German also having the meaning 'Kreuz') which brings us back to 'chiasm'. Dürr examines the strengths and weaknesses of each theory and eventually comes to the conclusion:

"Daß man dessenungeachtet das Werk mit Smend, Chafe und anderen als symmetrisch angelegt betrachten kann,bedeutet unseres Erachtens keinen Widerspruch zum eben Gesagten. Wie schon erwähnt, lassen gerade bedeutende Kunstwerke sehr wohl unterschiedliche Auslegungsmöglichkeiten zu. Ob man freilich darüber hinaus eine solche Symmetrie -- und ganz besonders die von Chafe unterstellte, nicht auf harmonischer Verwandtschaft, sondern auf einen bloßen Zählmechnismus gegründete Symmetrie -- als von Bach beabsichtigtes Zeichen des Kreuzes interpretieren darf, gehört wohl zu denjenigen Fragen, die für immer unbeantwortet bleiben werden." p. 123

"Notwithstanding the fact that this composition SJP (BWV 245)), can be seen as having a planned symmetrical arrangement as identified by Smend, Chafe and others, this does not, in our opinion, contradict what has just been previously stated. As already mentioned before, it is specifically significant works of art that do permit differing possibilities for interpretation. But whether you go beyond the point of assuming that Bach deliberately planned such a symmetry, particularly of the type which Chafe presumes, one not based on harmonic relationships but founded upon a simple method of counting movements according to which you might interpret the presence of a cross which Bach might have intended, then this becomes one of those questions which will forever remain unanswered." |

|

Peter Smaill wrote (April 3, 2006):

[To Raymond Joly] Mea maxima culpa, I was a tad inaccurate. "Able was I ere I saw Elba" is of course the famous palindrome.

The greatest Christian one, from St Sophia in Constantinople via France to at least seven mediaeval English fonts, is in Greek,

NIΨON ANOMHMATA MH MONAN OΨIN

"Wash my transgressions, not only my face". (Font inscription).

A strict palindrome in German would be an interesting addition to the debate! |

|

Douglas Cowling wrote (April 3, 2006):

Chiasm in the Choral Works of Bach

Thomas Braatz wrote:

< It may be of interest that Alfred Dürr, in his book on the SJP (BWV 245), Bärenreiter, 3rd edition 1999, (I believe that this book has been translated into English) has a chapter entitled "The Overall Form in the Various Versions of the SJP", pp. 111-125. In this chapter, Dürr himself does not use the words 'chiasm' (only once in quotes from a work by Smend) or "palindrome' and simply refers to symmetry/symetrical throughout his detailed discussions of the various theories >

"Chiasm" tends to be used by literary scholars and theorists to suggest more than pure symmetry of structure. Bach certainly uses symmetrical structures in his choral works, the most famous being the "Magnificat", "Christ Lag in Todesabanden" and "Jesu Meine Freude" which all are arranged symmetrically on either side of a central movement.

Chiastic literary structures usually show a thematic movemnt -- a U-shape is often used as a metaphor -- with themes or characters "falling" to the low point of the U, at which there is some kind of transformative moment and a parallel movement of "rising". A famous example is Hardy's novel, "Tess of the d'Ubervilles" in which the central, low point is the exactly mid-point in the pagination of the book.

Chiastic structure is also a staple by New Testament scholars who see it particularly in the Johannine literature (Gospel of John, Epistles of John and Revelation). Here the chiastic theme is the descent of Christ from heaven to earth and death which is mirrored by the resurrection and return to God.

An example of true chiastic symmetry in Bach would be the Credo of the Mass in B Minor (BWV 232) where the work opens with God in heaven in the two-part chorus Credo - Patrem and then descends to the central, "low point" of the Crucifixus and then ascends to heaven again to return to the two-part chorus Confiteir - Et Exspecto. |

|

Ed Myskowski wrote (April 4, 2006):

Peter Smaill wrote:

< The greatest Christian one, from St Sophia in Constantinople via France to at least seven mediaeval English fonts, is in Greek,

NIΨON ANOMHMATA MH MONAN OΨIN

"Wash my transgressions, not only my face". (Font inscription). >

Wonderful (perhaps, deified)! One of my favorites - A man, a plan, a canal, Panama. Also via France, completed by USA. Bach connection? The canal route incorporated many natural brooks. |

|

Raymond Joly wrote (April 4, 2006):

[To Douglas Cowling] Maybe I retreated too quickly on the matter of chiasms and palindromes, for fear of having been dogmatic.

Thanks to Thomas Braatz for adducing the quotation from Dürr Doug Cowling alludes to below. It makes clear that we can describe what we want to draw attention to in a precise manner without borrowing terms from literary rhetoric. Why plague such a perfectly unambiguous word as PALINDROME with vagueness when MIRRORING, INVERTED SYMMETRY or whatever do the job perfectly?

By the way: some musical works exist that play backwards and forwards (long stretches of Berg's KAMMERKONZERT, Hindemith's HIN UND ZURÜCK), some that can play both ways simultaneously (MUSIKALISCHES OPFER), but do we have real palindromes, that will sound the same when played forwards and backwards?

Now about arches and chiasms. There are as many schools in literary studies as there are in playing Baroque sonatas, which is why I had never encountered the notion that an X is a U before. Is it unkind to say that that reminds me of the German idiom «Jemandem ein X für ein Y vormachen», pass off an X for a Y to someone, that is: fool him grossly? Of course, anyone gazing up an arch from the base of the column upwards to the keystone will meet the same elements in inverted order when he gazes down on the other side. I suggest we call an arch an arch. In order to have a chiasm, I would wish, for instance, the pillar bases on the left side and the capitals on the right to be adorned with fantastic animals whereas the pillar bases on the right and the capitals on the left would have flora. There is no fun to be had if the objects at the end of the branches of the X are not 1) clearly identifiable and 2) identifiable as being both cognate but not identical and 3) locally inverted: «A superman in physique, in intellect a fool» (Merriam-Webster, uncharitably [or maybe not? Am I prejudiced?]).

PS. German palindromes are to be found at: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Palindrom |

|

Thomas Braatz wrote (April 4, 2006):

Raymond Joly asked:

>>Do we have real palindromes, that will sound the same when played forwards and backwards?<<

Yes, Johann Gottfried Walther, in his 'Musicalisches Lexicon..." Leipzig, 1732, lists the Italian term:

Roverscio [sic] - umgekehrt, verkehrt

I remember playing a Haydn violin and piano sonata (which might have been simply a piano sonata before) which had a minuet that was played backwards at each repeat.

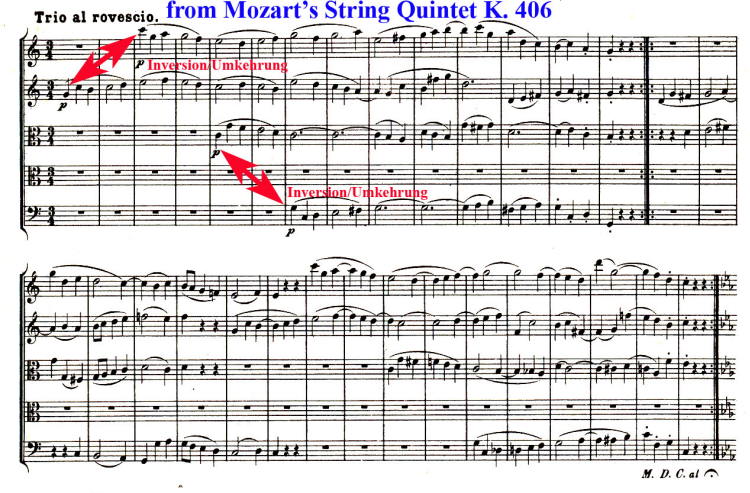

There is a Mozart Trio 'al Rovescio' (this is the usual spelling of the term) K 406.

There was some discussion about palindromic themes in Bach's music (search for 'palindrom' or 'palindromic' on the BCW).

Here is one link:

palindromic theme in the Art of the Fugue: http://www.bach-cantatas.com/BWV187-D.htm |

|

Ed Myskowski wrote (April 4, 2006):

Raymond Joly wrote:

< Maybe I retreated too quickly >

Au contraire, mon ami, perhaps not quickly enough. How are we to deal with the definition of chiastic structure as published in a popular, English language, Bach reference: Oxford Composers Companion. Useful for an English language group.

(1) Accept it, and use it for communication

(2) Refute it, with evidence. Clearly stated evidence. |

|

Raymond Joly wrote (April 4, 2006):

[To Thomas Braatz] Some verbal palindromes work both ways with the same meaning: ANNA (type A).

Some work both ways with a different meaning: ROMA / AMOR (type B). In music, I suppose "same meaning" (type A) would be "same melody". I am afraid I cannot imagine another example beyond a mordent: c-b-c, but I am no Bach. See the ART OF THE FUGUE link Th. Braatz provides above. Astounding. |

|

Ed Myskowski wrote (April 4, 2006):

Raymond Joly wrote:

< Some verbal palindromes work both ways with the same meaning: ANNA (type A).

Some work both ways with a different meaning: ROMA / AMOR (type B). In music, I suppose "same meaning" (type A) would be "same melody". I am afraid I cannot imagine another example beyond a mordent: c-b-c, but I am no Bach. See the ART OF THE FUGUE link Th. Braatz provides below. Astounding. >

Let me see if I can find our points of agreement:

(1) Palindrome is word with very specific verbal and musical meaning, respecting symmetry.

(2) Chiasm is a word (new to me, as I said) with perhaps even more specific symmetry, in a strict definition.

(3) Chiastic structure is a phrase (derived from chiasm, presumably) which refers to symmetry, but less strictly so than either palindrome or chiasm, at least as the phrase is defined in Oxford Composers Companion and as used by Peter Smaill. It struck me as potentially useful and concise, but I am beginning to wonder.

(4) Thomas Braatz posts are astounding, even when I have a differing opinion (not often). As as source of facts and data, unsurpassed. |

|

Ed Myskowski wrote (April 4, 2006):

Raymond Joly wrote:

< Some work both ways with a different meaning: ROMA / AMOR (type B). >

In the interests of being agreeable, I kept this separate. If a palindrome, by definition, reads the same in either direction, how does it have a different meaning, one way from the other? |

|

Thomas Braatz wrote (April 4, 2006):

Ed Myskowski wrote:

>>Let me see if I can find our points of agreement:

(1) Palindrome is word with very specific verbal and musical meaning,respecting symmetry.

(2) Chiasm is a word (new to me, as I said) with perhaps even more specific symmetry, in a strict definition.

(3) Chiastic structure is a phrase (derived from chiasm, presumably) which refers to symmetry, but less strictly so than either palindrome or chiasm, at least as the phrase is defined in Oxford Composers Companion and as used by Peter Smaill. It struck me as potentially useful and concise, but I am beginning to wonder.<<

Here are quotations in which the word appears in musicological contexts:

Here is the context for the only instance of 'Chiasm' and its extensions in the MGG1, Bärenreiter, 1986: [from the article on J.S.Bach by Friedrich Blume - this, as in the case of Alfred Dürr's comment, points to Friedrich Smend as the originator of this term as applied to Bach's music]

>>Nicht nur durch kontrapunktische Techniken, auch durch Formen können solche Assoziationen ausgedrückt werden (auf das häufige Vorkommen des sog. Chiasmus hat Smend aufmerksam gemacht). Bachs ganzes Werk ist voll von derartigen hintergründigen Beziehungen, die z. Tl. so verborgen sind, daß sie nicht dem Hörer zum Bewußtsein kommen, sondern sich nur beim Studium der Part. erschließen. Sie sind für Bach Ausdruck des Dienstes an der Wortverkündigung gewesen, der der Musik als »laudatio Dei« aufgegeben war, gleichzeitig aber auch rationale Spekulationen, die in der mathematisch-wissenschaftlichen Auffassung der Musik ihren Sitz hatten und sich als »lusus ingenii« an den Kenner richteten. Er ist »Esoteriker, und Zeit seines Lebens hat er mit Worten und Begriffen eine Art Geheimkult getrieben« (Schering).<<

("Such associations can be expressed not only through the use of contrapuntal techniques, but also by means of (structural) forms (Smend first brought our attention to the frequent occurrence of the so-called 'chiasm' {in Bach's music}). Bach's entire oeuvre is replete with hidden/enigmatic relationships/connections of this type, which sometimes are so concealed, that a listener will not be conscious of them, but which will reveal themselves only by studying the score. These connections were the way Bach had of expressing his service in proclaiming the 'Word' (the text), a task which was assigned to music as part of 'praising God', but at the same time they were also rational speculations which were based upon a mathematical-scientific understanding of music and directed at the connoisseur as 'ingenious mind games'. Bach is someone steeped in esoteric matters, and throughout his whole life he carried on a kind of 'secret religion' involving words and concepts.")

From the Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, 2006, acc. 4/3/06:

The article on Johannes Brahms

>>Chiastic tonal planning and a final chorale-like song on the theme of human redemption in the seven strophic Marienlieder op.22 (1859) may have been inspired by Bach's cantatas.<<

George S. Bozarth and Walter Frisch

An aricle on "Versified Office"

>>A form of medieval Office, of Carolingian origin and common until about 1500, in which some or all of the antiphons and responsories are in verse. The vast majority are for saints' days, but some are for particular Sundays or other feasts, including Advent, Trinity and Corpus Christi. Both metrical and accentual versification systems were used, and the verse was frequently rhymed. At least 1500 such Offices are known, some consisting of as many as 50-60 versified items (and there are countless others with only a single item); they are found throughout western Europe, including regions such as Scandinavia and Poland, whose conversion to Christianity was relatively late.

Among the oldest surviving 10th-century Offices is that for the Trinity composed by Stephen of Liège. It is written in highly structured prose (with several rhymes), and is mainly compiled from verses from the Bible and hymn doxologies, including parts of Alcuin's hymn to the Trinity. In the first antiphon at Lauds, in iambic dimeter, the three persons of the Trinity are not referred to by name but as 'Trinitas aequalis' and 'una Deitas':

Gloria tibi, Trinitas

aequalis, una Deitas,

et ante omnia saecula

et nunc et in perpetuum.

The word order used in these terms is known as 'chiastic', since equivalent parts of speech form the shape of the Greek letter chi (χ). In the third antiphon at Lauds, based on a hymn to St Vedastus by Alcuin, the subject is 'gloria', to which two similar verbs, 'resonet' and 'resultet', are tied, both with forms of 'laus'; the singers are present in the text through the phrase 'in ore omnium', and the verse form is a Sapphic stanza:

Gloria laudis resonet in ore

omnium patris genitaeque prolis,

Spiritus sancti pariter resultet

laude perenni.

Although this Office is not a historia inthe narrative sense, it was known from an early date as the historia de Trinitate, and like the Office for Christmas was in widespread use until the Second Vatican Council.<<

Ritva Maria Jacobsson

From the article "Music of Canada" (Scottish and Irish Influences):

>>In contrast with neighbouring Gaelic Scots tradition, the oldest English-language songs were almost exclusively narrative rather than lyric. About 100 Child ballads, generally originating before 1800, have been collected in many variants, some in more complete versions than those found overseas, though seldom more than two or three from a single singer. Ballad texts featured an inverted chiastic structure, parallel and framing stanzas and such commonplace, recurrent phrases as 'milk-white steed' migrating from song to song. Often known only in fragments, the stories generally opened in the middle of the action and leapt from scene to scene, lingering on dramatic episodes. Singers reportedly valued the ballads' tales of tragic love for their arcane settings, dramatis personae (including monarchs and nobles) and supernatural elements.<<

Jay Rahn

[Will someone explain 'an inverted chiastic structure'? When you turn an 'X' (Chi) upside down, how is it different or meaningful compared to a right-side up 'X']

Discussion of "Actus Tragicus" (BWV 106) by Eric Chafe from his book "Tonal Allegory in the Vocal Music of J.S.Bach" University of California Press, 1991 p. 120

>>In what is for Bach the pre-Leipzig form of this melodic line we have the image of the tonal structure of the entire cantata (Example F Eb F). This final emblem of the incarnation and atonement is the quintessential instance of a chiastic theme (in which the central tone, root of the E flat tonic triad, even aligns with the syllable "Chri" in the text), just as the "Actus Tragicus" (BWV 106) itself is the paradigm of the chiastic cantata, placing Christ at the center of Scripture, God's time, and the spiritual life of faith.<< |

|

Alain Bruguieres wrote (April 4, 2006):

Raymond Joly wrote:

<< Some work both ways with a different meaning: ROMA / AMOR (type B). >>

Ed Myskowski wrote:

< In the interests of being agreeable, I kept this separate. If a palindrome, by definition, reads the same in either direction, how does it have a different meaning, one way from the other? >

Well. Palindrome means 'run backwards'. Applied to a word or sentence, it means that you can read it from left to right or from right to left. It being understood that it means something both ways (otherwise any sentence is a palindrome!).

Now one special case is when it reads the same thing both ways. Probably more interesting is a palindrome which reads different things! But apparently, most of the time, it is assumed that the 'inversus' is equal to the 'rectus'. Let's call that a strict palindrome. Note that if B is the inversus of A, then AB always is a palindrome in the strict sense!

Does anyone know a palindrome which says one thing from left to right, and the contrary from right to left? |

|

Peter Smaill wrote (April 4, 2006):

[To Thomas Braatz] Whether or not palindrome or chiasm (John Eliot Gardiner uses this latter word) are quite exact expressions for the symettry-patterns in Bach, we do seem to have unusual and quite deliberate structural plays based on focal point in three ways in Bach:

By arrangement of the order of vocal components (as in the analyses of SJP (BWV 245), BWV 63, BWV 4, Jesu meine Freude)

By arrangement of both vocal components and words (I argue this for BWV 134)

Purely by note pattern symmetry (Art of Fugue (BWV 1080))

I would like to add another hybrid, that is the Chorale for BWV 26, "Ach wie nichtig, ach wie fluchtig".

Not only is there a mirror- word / palindromic play ("NEBEL and LEBEN" occur in capitals in the original text of the chorale , but the chorale tune's first two lines (bar a passing semiquaver) are musically symettrical.The setting is that set out in the Novello edition of the Orgelbüchlein.

It may be , apart from KdF, that the expression "chiastic", while strictly debatable, is the most appropriate given the association of several texts with either St John's Gospel (full of chiastic expressions) , or music related to death and resurrection. |

|

Raymond Joly wrote (April 4, 2006):

[To Ed Myskowski] In a former email, you were kind enough to point out that I should have opened reference books before I wrote a dissertation on what is a chiasm and what is not. That is a kind of lesson I acknowledge gratefully. The Web is dangerous: the feeling of immediate communication easily leads one to be as rash as in conversation; but scripta manent.

If I have time, I will do my homework and see what solid stuff I can find. For now, just two little things:

1) The fun in palindromes (for those who find them funny) is the difficulty overcome. You cannot cheat. There are some beautiful "free canons" in music; an exquisite one concludes volume 1 of Bartók's MICROCOSMOS. I do not think a "free palindrome" can be deemed anything but a failure.

2) It has occurred to me that inverted symmetry is essential for a chiasm, but that the human mind constantly plays games with time and space. A (base) - B (column) - C (capital) occur as A-B-C on both sides of the arch: no inversion, no chiasm. But they become A-B-C-C-B-A when you turn space into time and your eye climbs up on your left side and THEN down on the right. |

|

Raymond Joly wrote (April 4, 2006):

Raymond Joly wrote:

<< Some work both ways with a different meaning: ROMA / AMOR (type B). >>

Ed Myskowski wrote:

< In the interests of being agreeable, I kept this separate. If a palindrome, by definition, reads the same in either direction, how does it have a different meaning, one way from the other? >

I am an inexhaustible source of blunders. Did I write that a palindrome reads THE SAME in either direction? It should be: reads in both directions, producing some meaning either way.

An other one: the German phrase for fooling someone is not "pass off an X for a Y", but an X for a U. Origin: X and V as Roman numerals for ten and five (u/v and U/V have been more or less confused in writing for centuries).

Sorry ! |

|

Thomas Braatz wrote (April 4, 2006):

Peter Smaill wrote:

>>It may be , apart from KdF, that the expression, "chiastic", while strictly debatable, is the most appropriate given the association of several texts with either St John's Gospel (full of chiastic expressions), or music related to death and resurrection.<<

Here are two quotations from Eric Chafe's book "Tonal Allegory in the Vocal Music of J. S. Bach" University of California Press, 1991:

p. 309 (in the discussion of SJP):

>>John's Gospel is famous for what have been called its "typical chiastic patterns," and of these patterns the trial is the best known and the most conspicuous, that is, episode one resembles episode seven, episodes two and six, and three and five are similar, while John shifted the scourging to place it at the center of the trial (episode four), the only scene that involves the "Kriegsknechte" rather than Pilate or the crowd. The abstract quality of John's arrangement is underscored by the correspondence of the seven episodes of John's trial to John's seven signs, seven discourses, and "I am" sayings.<<

p. 311

>>He [Bach] certainly meant to create points of culmination and resolution after the narrative of the crucifixion and the royal inscription. Perhaps early on he meant the chorale "In meines Herzens Grunde" to express the joining and internalizing of the two events. He might also have intended for the subsection culminating with this chorale to have a symmetrical (chiastic) structure -- a visual realization of the cross and name. While John did not intend his chiastic structures to be visual representations of either the cross or the letter Chi, it is quite possible that symmetry bore thisassociation for Bach. [the footnote refers to Friedrich Smend's article "Luther and Bach" in the Bach-Jahrbuch 37 (1947)] The figurative sense of the cross, symbolizing earthly trial and tribulation, might then have been applied to the trial of Jesus. Bach must also have intended the idea of antithesis and resolution to be conveyed by the symmetrical structure. How Bach decided these issues is, perhaps, not important; interpreting the subsection itself makes his intentions clear. Bach's equivalent to John's symmetrical trial, the segment Friedrich Smend called the "Herzstück", comprises, in my reinterpretation of Smend's concept, a flat/sharp/flat tonal grouping in which two choruses of the first key area--"Kreuzige ihn" (G minor) and "Wir haben ein Gesetz" (F major)--are transposed into sharps and heard in reverse order with new texts in the second: now "Lässest du diesen los" (E major) and "Weg mit dem, kreuzige ihn" (F sharp minor)....<<

From the OCC

>>In movement 3 [of BWV 101] ornamented lines of the chorale melody alternate with simple recitative.

Movement 4 stands at the centre of the cantata's

chiastic structure:

1. Chorus (connected or balanced with 7. Chorale

2. Aria with 6. Duet

3. Recitative with Chorale with 5. Recitative with Chorale

4. Aria (the midpoint of the structure)<< Robin A. Leaver

The OCC lists 'chiastic structure' not under 'Structures' but under "Styles, practices, and concepts"

I have been trying to find the first use of 'chiastic/chiasm' as applied to Bach. What I have determined thus far is:

Friedrich Smend seems to have been the first to apply this term to describe musico-textual structures in Bach's music. This is recognized as a fact by Alfred Dürr and Eric Chafe, with the latter being uncertain regarding the first appearance of this term. Alfred Dürr simply states that the phrase "chiastisch-zyklisch" was not originally used in Smend's article on the SJP (1926), but appeared later on. Chafe is uncertain whether Smend used the term in is discussion of the SMP (1928), but Chafe does quote Smend's 1947 article (see above) where the term does appear. It should not surprise any reader familiar with much more wide-spread use of this term in theology that Smend was a theologian among other things. This would explain how and why he might have been the first to apply this term in the discussion of Bach's music and possibly even in musicology generally. Very likely Smend's first application of this term was after WWII. Before that time he used the word 'symmetry' in all of its forms repeatedly. In 1926 Smend introduced the term "Herzstück" (the core, central section) and used "Rahmenstück" for the framing structures that are not part of the "Herzstück". |

|

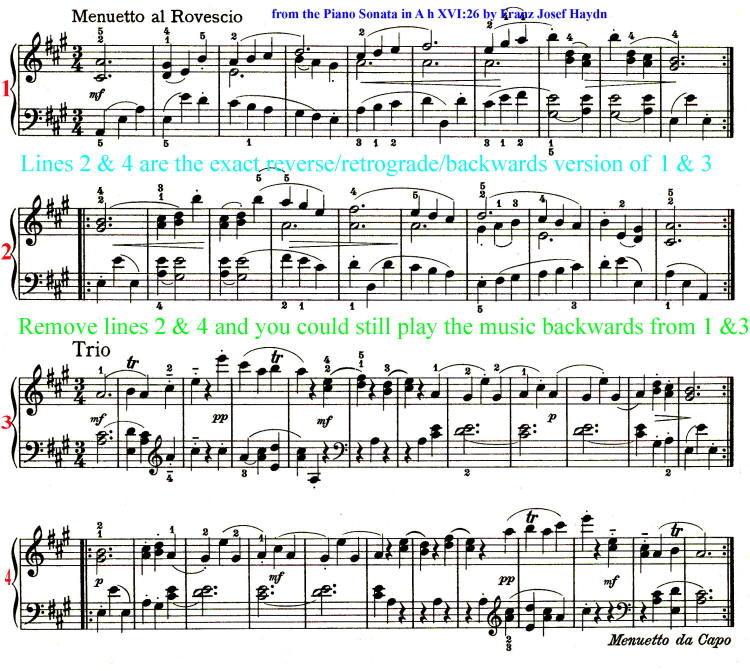

Bradley Lehman wrote (April 4, 2006):

Haydn ndyaH

Thomas Braatz wrote:

< I remember playing a Haydn violin and piano sonata (which might have been simply a piano sonata before) which had a minuet that was played backwards at each repeat. >

Piano sonata #26 in A, and symphony #47 in G. I used that movement in a university lecture a few years ago, where I handed out the piano score to everybody and I played the piece. I then asked what was special about it. They were looking right at it, including the title "menuetto al rovescio"; and in this piano score all the "forward" stuff was written in big notes, and all the "backward" stuff in smaller notes. Yet, NOBODY came up with the answer that it was exactly the same music going forward and backward, until I explained it directly.

This was in a class about observation, and patterns! Granted, it was an interdisciplinary course and not all about music; but I think somebody should have got it.

I didn't bother going into Maurice Ravel's menuet on the name of Haydn, which uses a musical theme derived from Haydn's name...going forward and then backward. Or, Schumann's "Carnaval" which plays rather similar games with the sequences "ASCH" and "SCHA", or his "Abegg" variations where he plays with his girlfriend's name right side up and then upside down. Or Shostakovich, taking such name-gaming to a crankier degree (quartet #8, etc etc) than any other non-serialist composers. |

|

Yoël L. Arbeitman wrote (April 4, 2006):

Bradley Lehman wrote:

< Piano sonata #26 in A, and symphony #47 in G. I used that movement in a university lecture a few years ago, where I handed out the piano score to everybody and I played the piece. I then asked what was special about it. They were looking right at it, including the title "menuetto al rovescio"; and in this piano score all the "forward" stuff was written in big notes, and all the "backward" stuff in smaller notes. Yet, NOBODY came up with the answer that it was exactly the same music going forward and backward, until I explained it directly. >

I wonder whether, in addition to sinistrograde and retrograde writing, there is any possibility of employing boustrephedon. As everyone knows on this very Greek list with Xasms and litotes and every other term of the Greek rhetoricians and even some Linear B, Greek writing (as we know it and hence Latin writing) took the opposite direction from its parent Phenico-Hebrew script via boustrephedon.

also I would appreciate knowing what the following means:

"La patria del diritto e del rovescio".

A music e-mate of mine who is a native Italian speaker says that the terms as reapplied here are based on their usage in tennis, a game that neither he nor I know much about.

I don't know whether music will be able to shed further light.

Thanks in advance, |

|

Bradley Lehman wrote (April 4, 2006):

< I wonder whether, in addition to sinistrograde and retrograde writing, there is any possibility of employing boustrephedon. >

I hope you've seen some of these wonderful ambigram creations: http://www.google.com/search?q=ambigrams

(And Douglas Hofstadter's books exploring such....) |

|

Raymond Joly wrote (April 4, 2006):

[To Bradley Lehman] I am unwell and cannot go to the library. Please tell me what type of palindrome your Haydn sonata and symphony are:

Type 1. ANNA starting from the beginning = ANNA the other way round.

Type 2. ROMA / AMOR: makes sense both ways, but not the same sense.

That is: are the two pieces you mention like that subject in the ART OF THE FUGUE we heard about yesterday? Nobody can tell which way it is being played, since the melody is exactly the same no matter what end you start with. In your case, your audience would have heard a minuet twice without realizing that your eyes had moved from right to left and upwards when you were doing your exact repeat (ANNA).

Or did they enjoy two nice minuets, again not realizing what you were doing with your eyes? The melody derived from reading backwards was different from the first one, quite as fine maybe, but at any rate plausible: ROMA / AMOR.

I bet on ROMA, but I may be underestimating Haydn's cleverness.

By the way, since you mention Haydn ndyaH, can you tell me how they run their scales up after G when they want to pay homage to Schumann? The poor man must sound very different if he is honoured by an Englishman with a wretched little B and a German with an array of B's and H's, and indeed punning S's meaning E flat. |

|

Ed Myskowski wrote (April 4, 2006):

I hope this will be my final word on the topic. I tried to Google chiasm and music, but found the hits clogged by a band:

Band History:

I started the Chiasm project in the winter of 1997 while in grad school for molecular biology in Detroit as a creative outlet for my frustrations.

Just no telling to what lengths frustration will drive a graduate student! |

|

Bradley Lehman wrote (April 4, 2006):

< Piano sonata #26 in A, and symphony #47 in G. I am unwell and cannot go to the library. Please tell me what type of palindrome your Haydn sonata and symphony are:

Type 1. ANNA starting from the beginning = ANNA the other way round.

Type 2. ROMA / AMOR: makes sense both ways, but not the same sense. >

The minuet is your "type 2" -- it has 10 bars of decent-sounding music going all the way to the repeat double-bar, and then the music goes in complete reverse to make the repeated second half of the minuet.

Then the trio does the same, with 12 more bars of music going first forward, double bar, then all backward.

< By the way, since you mention Haydn ndyaH, can you tell me how they run their scales up after G when they want to pay homage to Schumann? >

No, it's Ravel doing the Haydn name. Ravel's menuet maps "H A Y D N" to B, A, D, D, G. He uses at least six different permutations of that, through the piece, plus some repetitions. (A readily available score: last piece in "Piano Masterpieces of Maurice Ravel" from Dover Publications, with all the H-A-Y-D-N marked.)

< The poor man must sound very different if he is honoured by an Englishman with a wretched little B and a German with an array of B's and H's, and indeed punning S's meaning E flat. >

Schumann in "Carnaval" opus 9 plays with three different combinations: ASCH (Bohemian town where another girlfriend of his lived...), SCHA (the notes of his own name that can be transliterated most readily into notes), and another version of ASCH. All three of these are laid out most directly in the "Sphinxs" movement, not played(!), in breves.

Eb (Es), C, B (H), A.

Ab (As), C, B (H).

A, Eb (Es), C, B (H).

Clara Schumann's edition, and maybe some others as well, goes through the treasure hunt of these four themes all the way through "Carnaval" and marks them with little crosses. It's usually the first three or

four notes of most of the movements. |

|

Ed Myskowski wrote (April 4, 2006):

Raymond Joly wrote:

< In a former email, you were kind enough to point out that I should have opened reference books before I wrote a dissertation on what is a chiasm and what is not. >

I certainly did not mean to make the point that severely. If I did, my apologies. In any case, the discussions are all voluntary, and we may well have nearly cleared the room with this one (as Peter Smaill warned us early on). I am still here, and have found it illuminating.

Beneath it all, I think we are striving to use language to promote accurate communication, and enjoy ourselves in the process. Pas de probleme, mon ami ! (Sorry, I have not yet mastered accents, umlauts, etc. for eMail. You know what I mean.) |

|

Thomas Braatz wrote (April 5, 2006):

Rovescio (2 meanings), retrograde, palindrome, etc.

I have two examples of 'al rovescio' (Haydn, Mozart) and each uses the term differently. Haydn's piano sonata menuetto is ROMA-AMOR, but Mozart's K. 406 'Trio al rovescio'is an inversion/"Umkehrung" (I am trying to think just how this might be explained in terms of "ROMA" (somebody help me out here if I get this wrong!): You see ROMA on your monitor, but now you turn your monitor around 180 degrees (or easier yet, with a drawing program you select the entire word "ROMA". With a program like Photoshop you can spin this word around 180 degrees so that the upside-down 'A' is on the extreme left and the upside-down 'R' on the extreme right. It's a somewhat strange looking "AMOR" with only the 'O' surviving the switch intact. But this is not what happens with Mozart's Trio. Now you will need to isolate/select each letter individually, say, for instance, only the 'R', turn it upside down and move it higher or lower (to represent the entry of the subject at a different pitch level) on the page, then the same for the 'O' which remains in the 2nd position from the left right behind 'R', etc., etc. The final result is a strange-looking, mirror-like reflection of "ROMA" with each letter still in the same sequence, but with each one now upside down and placed higher (or lower) on the page. This is much easier to actual see in the musical score (if you can read music). I will ask Aryeh Oron to post my examples on the BCW as part of this discussion.

In the meantime, here are some explanations I have extracted from the Grove Music Online which might help in 'coming to terms with these terms':

Al rovescio

(It.: 'upside down', 'back to front').

A term that can refer either to Inversion or to Retrograde motion. Haydn called the minuet of the Piano Sonata in A h XVI:26 Minuetto al rovescio: after the trio the minuet is directed to be played backwards (retrograde motion). In the Serenade for Wind in C minor K388/384a, Mozart called the trio of the minuet Trio in canone al rovescio, referring to the fact that the two oboes and the two bassoons are in canon by inversion.

Retrograde

(Ger. 'Krebsgang', from Lat. 'cancrizans': 'crab-like').

A succession of notes played backwards, either retaining or abandoning the rhythm of the original. It has always been regarded as among the more esoteric ways of extending musical structures, one that does not necessarily invite the listener's appreciation. In the Middle Ages and Renaissance it was applied to cantus firmi, sometimes with elaborate indications of rhythmic organization given in cryptic Latin inscriptions in the musical manuscripts; rarely was it intended to be detected from performance.

Cancrizans

(Lat.: 'crab-like').

By tradition 'cancrizans' signifies that a part is to be heard backwards (see Retrograde); crabs in fact move sideways, a mode of perambulation that greatly facilitates reversal of direction.

Palindrome.

A piece or passage in which a Retrograde follows the original (or 'model') from which it is derived (see Mirror forms). The retrograde normally follows the original directly. The term 'palindrome' may be applied exclusively to the retrograde itself, provided that the original preceded it. In the simplest kind of palindrome a melodic line is followed by its 'cancrizans', while the harmony (if present) is freely treated. The finale of Beethoven's Hammerklavier Sonata op.106 provides an example. Unlike the 'crab canon', known also as 'canon cancrizans' or 'canon al rovescio', in which the original is present with the retrograde, a palindrome does not present both directional forms simultaneously. Much rarer than any of these phenomena is the true palindrome, where the entire fabric of the model is reversed, so that the harmonic progressions emerge backwards too. Byrd's eight-voice motet Diliges Dominum is a polyphonic example in which at the halfway point the two voices of each pair exchange parts and present them backwards. It may be that the text's exhortation to 'love thy neighbour as thyself' suggested to Byrd the reflexive reprise to bring the music back to its starting-point. The two known examples in 18th-century music are both minuets. C.P.E. Bach's Minuet in C for keyboard (h216) has two eight-bar sections, the second a reversal of the first. The minuet of Haydn's Symphony no.47 (which appears also in the Piano Sonata hXVI:26 and the Violin Sonata hVI:4), composed in 1772, only a year or two after C.P.E. Bach's, is so exactly and proudly palindromic that Haydn wrote out only the first section, followed by the instruction 'Menuet al reverso'. Minuets, with their tendency to less sophisticated textures and harmonic rhythm than other genres of the Classical period, lent themselves more readily to such contrivances; hence, paradoxically, a tradition of simplicity and relaxation co-existed with one of intellectual devices in this context. When it is observed that only one 19th-century composer is known to have written a true palindrome, the reader's guesswork may begin with Brahms, or even Schumann, but probably not with Schubert. The true palindrome in Schubert's opera-melodrama "Die Zauberharfe" (1820) is not only a surprise but constitutes a technical tour de force. The harmonic thinking is far more venturesome than that in the Haydn minuet, as example 1 reveals (the example shows part of the original and the equivalent part of the retrograde); and the orchestra is now a Romantic one complete with trombones. A further innovation is the structural separation of the retrograde from the original, with 309 bars of music between them. In forming his retrograde, Schubert was compelled to allow himself some licence in the ordering of pitches and rhythms within a bar or half-bar. (A detailed commentary on this example appears in B. Newbould: 'A Schubert Palindrome', 19CM, xv, 1991-2, pp.207-14.) With the aof tonality by the composers of the Second Viennese School, the stringent harmonic demands of the palindrome were considerably eased. Berg's Lyrische Suite, Kammerkonzert and the film music in Lulu all make use of palindrome, and in Webern's Symphony op.21 the development of the first movement is a palindrome, with the succession of instrumental timbres reversed accordingly. In the music of these and later serialists, palindromic excursions have become, if not commonplace, less infrequent and less awesome as technical feats. A more remarkable 20th-century example is found in Hindemith's "Ludus tonalis" (1942), where the substantial Postludium is not merely a palindrome (or horizontal mirror image) of the equally lengthy Praeludium, but a vertical mirror image too, in which each strand within the texture appears in melodic inversion while the texture itself is also inverted so that the topmost strand becomes the lowest and the others migrate accordingly. Part of an extended multi-movement work which displays other symmetrical features too, this framing 'mirror palindrome' is a substantial example embracing several sections in different tempos.

Brian Newbould

>>More complex are the 'mensuration canons': canon by augmentation, diminution or by proportional changes of note values and canon by inversion or retrograde motion. In the canon by inversion ('canon per motu contrario per arsin et thesin') the direction of melodic progression is inverted in successive entrances, but in the canon by retrograde motion ('canon cancrizans, canone al rovescio' - 'crab canon') the canonic imitation is produced by reading the original melodic line backwards, so that the imitating part starts at the end rather than at the beginning of the piece.<<

>>The minuet of Haydn's piano sonata h XVI:26 in A, for example, is cast in the typical minuet and trio form, but, as indicated by its heading 'menuet al rovescio', the second half of each section is an exact retrograde of the first. Haydn's Symphony no.44 ('Trauer') and String Quartet op.76 no.2 both include minuet and trio movements that employ strict canon and irregular phrases to lend an unaccustomed seriousness to the form, as does the use of both canon and double counterpoint in the minuet of Mozart's Symphony no.40 (K.550).<< (Meredith Little)

>>Even the most famous secular example of retrograde, Machaut's "Ma fin est mon commencement", whose text gives away its design, has been admired more for the finesse with which the technique is used than for the chanson's other artistic merits. There is only one well-known example of retrograde in tonal music, apart from its use in puzzle canons: this is in the last movement of Beethoven's Hammerklavier Sonata, where an entire fugal exposition is based on the retrograde form of the original subject, retaining its 'backward' rhythm but being converted to the minor mode. In the 20th century retrograde has played an important part in the theory of Twelve-note composition, being one of three basic operations that can be performed on a 12-note set; retrograde is often used in conjunction with the other two, inversion and transposition.<<

William Drabkin

>>A new kind of theoretical canon came into being in connection with the Goldberg Variations, in which the canonic principle played a special part. In his personal copy of the Goldberg Variations Bach wrote in 1747-8 a series of 14 perpetual canons on the first eight bass notes of the aria ground (bwv1087), exploring the most varied canonic possibilities of the subject, subsequently arranging the individual perpetual canons in a progressive order, organized according to their increasing contrapuntal complexity. The types included range from simple, double and triple canons, retrograde canons and stretto canons to a quadruple proportion canon by augmentation and diminution. Nos.11 and 13 of this series are identical with bwv1077 and 1076 (depicted on Haussmann's Bach portrait of 1746).<<

Christoph Wolff

>>Both these aspects of design were subject to alteration. It became increasingly common during the Baroque era for the second half to relate more precisely to the first. In particular, the listener's comprehension of the form was aided by a 'rhyming' of the outer parts of each half. Thus the second half would often begin with a dominant version of the first half's opening unit or phrase, either briefly acknowledged or quoted extensively. An inversion of the material was also common, particularly in gigue movements (see, for instance, the Gigue from Bach's English Suite no.4 in F). In the Allemande from the same work, not only does the material appear in retrograde, but also the hands swap roles, the left hand now taking the melodic lead. This dominant version of material was often used as a springboard to regaining the tonic, albeit often only briefly before the harmony moved further afield.<<

W. Dean Sutcliffe

[All the above citations are from the Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, 2006, acc. 3/4/06] |

|

Ed Myskowsky wrote (April 5, 2006):

Rovescio (2 meanings), retrograde, palindrome, etc.

Thomas Braatz wrote:

< Palindrome. [...] >

This post has helped clear up my misunderstanding, I believe, based on the following:

(1) As a verbal rhetorical device, palindrome has a very restricted meaning.

(2) As applied to music, it covers a broader family of symmetrical devices, well defined, and best understood with graphic, score, and audible examples.

I reiterate my previously stated position: extra detail is always preferable to insufficient. I apologize if I have made any careless comments based on applying the literary definition only. And to Peter Smaill, look how many folks are still in the room! |

|

Thomas Braatz wrote (April 5, 2006):

Thomas Braatz wrote:

>>I will ask Aryeh Oron to post my examples on the BCW as part of this discussion.<<

Aryeh Oron has kindly consented to do this and they are already ready to be viewed at the bottom of the page for this ongoing discussion at: http://www.bach-cantatas.com/Topics/Chiasm.htm [See below] |

|

|

|

|

|

Ed Myskowsky wrote (April 5, 2006):

Article about chiastic/symmetrical structures in JSB

johseb2 wrote:

< The greater part of this chapter is about chiastic and symmetrical patterns in the major vocal works - the passions, the masses, the christmas oratorio, the magnificat etc. >

I have just posted several comments, including "we have driven chiasm into the chasm." Obviously wrong. Peter Smaill will be astounded that the discussion is actually drawing people into the room. Is there is a zeugma lurking here? |

| |

|

General Topics:

Main Page

| About the Bach Cantatas Website

| Cantatas & Other Vocal Works

| Scores & Composition, Parodies, Reconstructions, Transcriptions

| Texts, Translations, Languages

| Instruments, Voices, Choirs

| Performance Practice

| Radio, Concerts, Festivals, Recordings

| Life of Bach, Bach & Other Composers

| Mailing Lists, Members, Contributors

| Various Topics

|

|

|