|

|

Cantata BWV 127

Herr Jesu Christ, wahr' Mensch und Gott

Commentary |

|

Contents |

|

Philipp Spitta: "Johann Sebastian Bach"

Albert Schweitzer: "J. S. Bach"

Woldemar Voigt: "Die Kirchenkantaten Joh. Seb. Bach’s"

Friedrich Smend: "J. S. Bach: Kirchen-Kantaten"

W. Gillies Whittaker: "The Cantatas of Johann Sebastian Bach"

Alfred Dürr: "Johann Sebastian Bach: Die Kantaten"

Alec Robertson: "The Church Cantatas of J. S. Bach"

Ludwig Finscher: Commentary to Harnoncourt/Leonhardt Complete Cantata Series on Teldex

Eric Chafe: Section on the SMP in “Tonal Allegory in the Vocal Music of J. S. Bach”

Eric Chafe: “Analyzing Bach Cantatas”

Christoph Wolff: Liner Notes to Koopman Cantata Series |

| |

|

Philipp Spitta: "Johann Sebastian Bach" |

|

[Dover 1959, 1971 translation of original from 1873-1880] vol. 3, pp. 101-102 |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Albert Schweitzer: “J. S. Bach” |

|

[Dover, 1966 reprint of Breitkopf & Härtel, 1911] vol. 2 p. 94-95 |

|

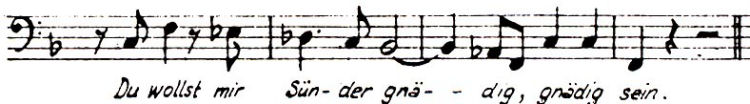

THE RHYTHM  |

|

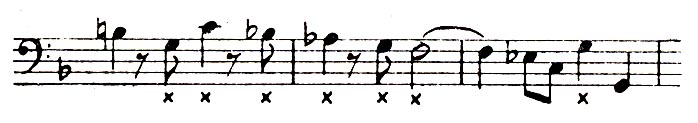

The rhythm  is mostly associated by musical people with the idea of dignity or solemnity. It is used in the grave section of the old French overture with the same signification as in the Graal scene in Parsifal. The E flat prelude for organ at the beginning of the collection of the greater catechism chorales illustrating the Lutheran doctrine is worked out in this rhythm; as it needs to be unusually majestic. Bach employs it again in the Easter cantata Christ lag in Todesbanden (No. 4), to express the sixth verse, "So feiern wir das hohe Fest" ("So we celebrate the high feast"). In the cantata for Palm Sunday, Himmelskönig, sei willkommen (No. 182) it is prompted by the word "Himmelskönig“ ("King of heaven") —

is mostly associated by musical people with the idea of dignity or solemnity. It is used in the grave section of the old French overture with the same signification as in the Graal scene in Parsifal. The E flat prelude for organ at the beginning of the collection of the greater catechism chorales illustrating the Lutheran doctrine is worked out in this rhythm; as it needs to be unusually majestic. Bach employs it again in the Easter cantata Christ lag in Todesbanden (No. 4), to express the sixth verse, "So feiern wir das hohe Fest" ("So we celebrate the high feast"). In the cantata for Palm Sunday, Himmelskönig, sei willkommen (No. 182) it is prompted by the word "Himmelskönig“ ("King of heaven") — |

|

|

|

The same rhythm occurs in several arias in which mention is made of the godhood of Jesus. In the Christmas cantata Gelobet seist du, Jesus Christ (No. 91), it elucidates the text "Die Armut, so Gott auf sich nimmt" ("God takes poverty upon Himself”) — |

|

|

|

It is found again in the first chorus of the cantata Herr Jesu Christ, wahr' Mensch und Gott (No. 127). Even the phrase "Fürst des Lebens" ("Prince of life") in an aria in the cantata Der Himmel lacht, die Erde jubilieret (No. 31) is enough to make Bach feel justified in introducing the rhythm of majesty — |

|

|

|

p. 367:

The accompaniment to the first chorus of the cantata for Quinquagesima Sunday, Herr Jesu Christ, wahr'r Mensch und Gott (No. 127), is wholly based on the rhythm of solemnity. It will be remembered that in an aria of the cantata Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ (No. 91) Bach employs this rhythm to express the text "God takes poverty on Himself", which likewise deals with the divine and human nature of Jesus. Thus the music in each case represents the divine majesty. As Quinquagesima Sunday, however, introduces the period of the Passion, in the cantata for that day Bach makes the strings and wind give out alternately the chorale "Christ, du Lamm Gottes", in a solemn rhythm.

Comments:

1. My quarrel with Schweitzer is that the examples of dotted rhythms involve dotted jumping intervals, whereas BWV 127/1 uses in its ‘wave’ motif which Bach indicated should even be slurred and not played staccato. Also the notion of a written-out ribattuta contradicts the jumping, dotted intervals that Schweitzer is referring to here. |

| |

|

Woldemar Voigt: “Die Kirchenkantaten Joh. Seb. Bach’s” |

|

[Breitkopf & Härtel, Leipzig, 1918] pp. 113-114

“Herr Jesu Christ, wahr’r Mensch und Gott.”

Durchweg meisterlich und von sehr großer Wirkung. Herrlich ist der Klang der Orchestersätze im ersten Chor, wo übrigens der eingefügte (zweite) Choral “Christe, du Lamm Gottes” durch die Orgel oder Klarinetten kräftig gestützt werden muß, um zur Geltung zu kommen.

Die Sopranarie mit der ganz aparten Begleitung ist von jener süßen, fast weiblichen Schwärmeri erfüllt, die bei dem männlichsten und strengsten aller Komponisten so wunderbar berührt; die Baßarie hat eine stolz zuversichtliche Haltung und biete dem Sänger eine der dankbarsten Aufgaben. Der Anklang an “Sind Blitze, sind Donner” auf S. 157 [23] ist auffallend; man möchte daraus schließen, daß das Stück nicht *nach* der Matthäuspassion komponiert sein könnte – aber andere Argumente sprechen doch stark dagegen.

[This cantata displays great mastery throughout and can have a powerful effect upon the listener. The sound of the orchestral introduction and the intervening interludes of the first chorus is splendid indeed. Incidentally, there is embedded in these orchestra sections a second chorale “Christ, you Lamb of God” [Agnus Dei] which needs to be strongly supported by having it played also on the organ or by using clarinets, so that it will be properly heard.

The soprano aria, with its very unusual accompaniment, is replete with a sweet, almost feminine romantic passion, which causes one to wonder how this can stem from the pen of one of the most masculine and strictest of all composers. The bass aria has a proud, confident attitude and offers the singer a most rewarding challenge. One section is so noticeably reminiscent of “Sind Blitze, sind Donner” that one is almost forced to conclude that this piece could not have been composed after the SMP – but other arguments speak strongly against this possibility.]

Comments:

1. It is interesting that even with or just because the instrumental and choral forces were larger for performing Bach’s cantatas during Voigt’s time, he finds it necessary to point out to conductors that the untexted chorale melody line must not ‘go under’ or ‘get lost’ amidst everything else that is going on. The suggested use of the organ would allow the conductor to judge just how loud the organ would have to be to provide the proper balance. The use of clarinets as replacements for original instruments goes back to the early 19th century.

2. Voigt would find himself vindicated in regard to his observation about the chronology of this cantata. Since Spitta, and perhaps even earlier, this cantata was considered to belong to Bach’s very late period based upon the false appraisal of the watermarks. Serious changes in this chronology occurred in the 1950s and 1960s, particularly as a result of renewed study of watermarks and penmanship. The most important contributors in this regard were Alfred Dürr and Yoshitake Kobayashi. |

| |

|

Friedrich Smend: "J. S. Bach: Kirchen-Kantaten“ |

|

[Berlin,1948, 1950] VI. 41-44

Herr Jesu Christ, wahr Mensch und Gott

Kantate 127

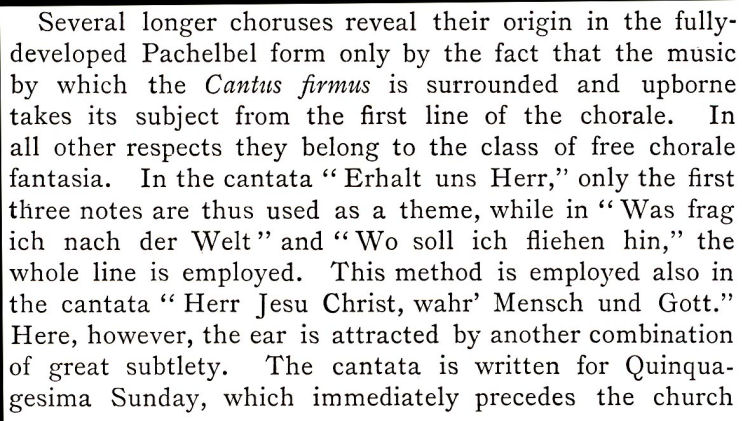

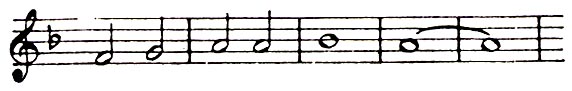

Unter sämtlichen erhaltenen Kantaten Bachs ist dies vielleicht die bedeutendste. Sie gehört in den letzten Lebensabschnitt des Meisters; man gewinnt den Eindruck, als ob er in ihr gewissermaßen die Summe seines gesamten Kantatenschaffens habe ziehen wollen. Passionsgedanken stehen, dem Charakter des Sonntags Estomihi entsprechend, an der Spitze des Werkes. Mehrfach kann man auch Beziehungen zum Evangelium des Sonntags (Luk. 18, 31—43) erkennen. So weist die Schlußzeile des Eingangschorals auf Luk, 18, 38 u. 39 hin; das erste Recitativ erwähnt den Zug Jesu hinauf nach Jerusalem (Luk, 18, 31). Diese Passionsgedanken aber verbinden sich mit Todesbetrachtungen; denn das der Kantate zugrunde liegende Lied Paul Ebers ist ein Sterbelied, Anfangs- und Schlußstrophe des Chorals sind, wie fast immer in den Kantaten dieser Zeit, in den Ecksätzen wörtlich beibehalten, die mittleren in den dazwischenstehenden Solosätzen (mit gelegentlicher Zitierung einzelner Zeilen) paraphrasiert. Die das Ganze beherrschende Melodie, schon 1562 mit dem Erstdruck des Chorals gemeinsam veröffentlicht, stammt aus dem französischen Psalter: |

|

|

|

Im Eingangschor (F dur); Besetzung des Orchesters: 2 Schnabel-flöten, 2 Oboen, Streicher mit Orgel) bildet sie den im Sopran liegenden Cantus firmus in der hier notierten Wertgröße (Haupttonschritte in Viertelnoten), Vom ersten bis zum letztTakt des Satzes aber hören wir im Orchester und in den begleitenden Chorstimmen beinahe ununterbrochen die erste Zeile, in ihren Notenwerten auf die Hälfte verkleinert (per diminutionem) in dichtester Folge, oft auch mit sich selber verschränkt, in ständigem Wechsel der Klangfarbe; der Tonhöhe, des Tongeschlechts: |

|

|

|

Der Name des Herrn Jesu Christ, der wahrer Mensch und wahrer Gott ist, wird ununterbrochen angerufen, der Name dessen, der nach Jerusalem zieht, um am Kreuz zu sterben.

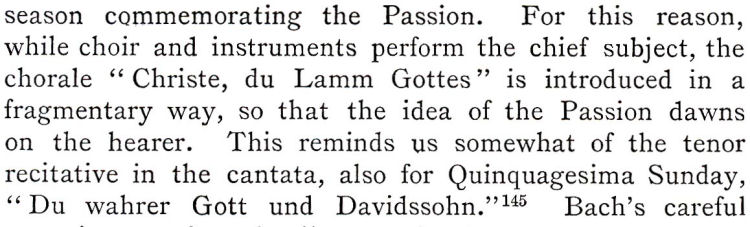

Dieser zweite Gedanke, der an Christi Tod, findet musikalisch darin seinen Ausdruck, daß in unserm Satz die Passionsweise „Christe, du Lamm Gottes” als zweiter Cantus firmus vollständig durchgeführt wird. Die Passionsmelodie ist allein dem Orchester anvertraut und erscheint in allen drei Instrumentengruppen (den Flöten, den Oboen, den Streichern), dazu in verschiedenen Tonarten (F dur und C dur); mit dem Hauptchoral verglichen in verdoppelten Notenwerten (per augmentationem; Haupttonschritte in halben Noten): |

|

|

|

So wird dies überwältigende Stück zu einem vollständigen Doppelchoral. Aber auch hiermit noch nicht genug: Bereits im Orchestervorspiel und dann mehrfach innerhalb des Stückes tritt im Orgelbaß ein dritter Choral hinzu: |

|

|

|

Es ist die erste Zeile der Haßlerschen Melodie, die zuerst dem Sterbelied von Christoph Knoll „Herzlich tut mich verlangen” beigelegt wurde, um später, nicht am wenigsten durch Bachs Matthäus-Passion, in Verbindung mit Paul Gerhardts Liede „O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden” eine der klassischen Passionsweisen zu werden. In ihr sind also Sterbe- und Passionsgedanken unlösbar verschmolzen, Einmal — in der Schlußzeile — tritt sie auch in die Singstimmen ein: |

|

|

|

Text und Ton faßt hiermit alles, was dies tiefsinnige und klanglich doch so durchsichtige Tonstück sagt, zusammen

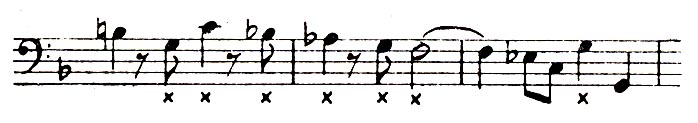

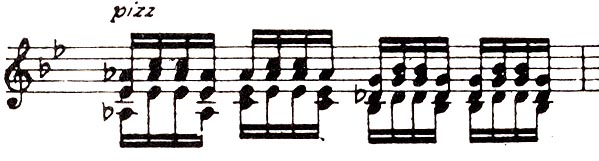

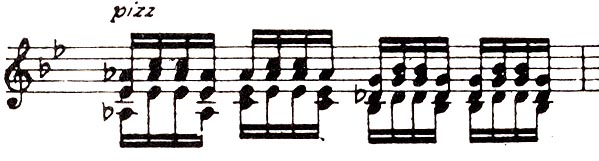

Ein nur vom Basso Continuo begleitetes Tenorrecitativ, in dem der Inhalt der 2. und 3. Choralstrophe zusammengedrängt ist, leitet zu der die 4. Strophe von Ebers Lied paraphrasierenden Sopranarie „Die Seele ruht in Jesu Händen” (c moll) über. Wenn man sagen muß, daß der Eingangschor unter Bachs Chorälen seinesgleichen nicht hat, so ist man versucht, unser Stück ebenso aus allen Bachschen Arien herauszuheben. Instrumentalsolist ist die Oboe, Die beiden Schnabelflöten begleiten, gestützt von kurzen Akkorden der Orgel, deren Baßnoten von den Violoncelli und den Kontrabässen pizzicato mitgespielt werden, in tupfenden Achteln: |

|

|

|

Ein unendlich schmerzliches Sehnen, aber auch der Vorgeschmack unaussprechbaren Friedens liegt in diesen Klängen, zumal wenn sich die Sopranstimme dazugesellt, und wir nun die Kantilene im Zwiegespräch zwischen Sänger und Bläser hören. Und doch hat Bach das Höchste für den Mittelsatz aufgespart. Tonartlich wendet sich das Stück nach Dur; zunächst in As-, dann in Es-Dur läßt die Oboe ihre nun wahrhaft tröstlichen Linien erklingen, wie im Hauptteil der Arie von den Flöten und der Orgel mit den Pizzicatobässen begleitet. Die Singstimme aber gibt der Sterbenssehnsucht, ja der Sterbensfreudigkeit mit den Worten Ausdruck: „Ach, ruft mich bald, ihr Sterbeglocken”. Und schon glauben wir sie zu hören. Wir sind genau im Mittelpunkt der Arie; da setzt das Streichorchester pizzicato mit Sechzehntelakkorden ein: |

|

|

|

Nur vierundeinhalb Takte lang lauschen wir dem Geläute; es ist bloß eine Vorahnung jener kommenden Seligkeit, die mit diesem Glockenklang angedeutet werden soll, und länger als nur wenige Augenblicke darf Ohr und Herz sich ihm nicht hingeben. Aber die Freude auf den Tod ist überschwänglich, „weil mich mein Jesus wieder weckt”.

Die Auferweckung der Toten aber bedeutet Auferweckung zum Gericht an jenem Tage,

Wenn einstens die Posaunen schallen,

Und wenn der Bau der Welt nebst denen Himmels-Vesten

Zerschmettert wird zerfallen,

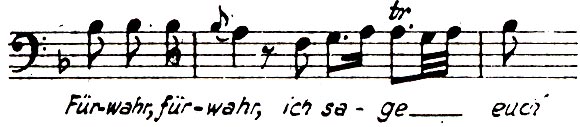

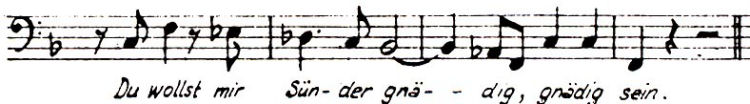

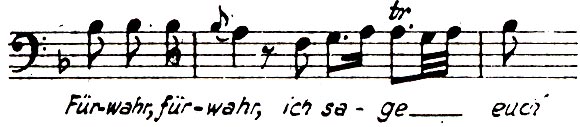

In allerstärkstem Gegensatz zu dem vorhergehenden Stück erklingen diese Worte zu Beginn des nächsten Satzes, der im Anschluß an die 5. und 6. Strophe Ebers Jesus-Worte aus Joh. 5, 24 u. 25 und Joh. 8, 52 vor unsere Seele stellt. Hört man die ersten Takte dieses Baßrecitativs, bei dem zur Orgel das Streichorchester mit pochenden Akkorden, eine Solotrompete mit Fanfarenklängen hinzutreten, so fühlt man sich in viel frühere Zeit des Bachschen Schaffens zurückversetzt. Das Stück erinnert unmittelbar an das Recitativ „Erschrecket, ihr verruchten Sünder”, das Bach in den ersten Leipziger Jahren der in Weimar entstandenen Kantate „Wachet, betet, betet, wachet” (Nr. 70) einfügte, Wie jener rund zwanzig Jahre früher komponierte Satz, so gliedert sich auch der unsere in zwei kontrastierende Hälften. Auf das Bild des Schreckens folgt der Trost unmittelbar, Mit Takt 14 fällt das Recitativ in festen Rhythmus (a tempo giusto); nur vom Continuo begleitet singt der Baß: |

|

|

|

Mit dem wörtlichen Choraltext Ebers kehrt die erste Zeile der Weise aus dem französischen Psalter wieder, auch vom Instrumentalbaß aufgenommen, und wird 7 Takte lang durchgeführt. Ohne formal deutliche Trennung geht darauf das Stück in die- zweite Arie (Baß, Trompete, Streicher, Orgel; C dur) über. Wie sich hier die Kühnheit des Ausdruckes und die Strenge der Form verbinden, das ist das Kennzeichen der absoluten Meisterschaft: Dreimal wird mit drohenden Klängen der Instrumente, mit leidenschaftlichster Deklamation der Singstimme der Untergang von Himmel und Erde gemalt; dazwischen treten, nur von der Orgel begleitet, Durchführungen unserer ersten Choralzeile, wie sie (a tempo giusto) vom Recitativ zur Arie hinübergeleitet hatten. Im Mittelpunkt der Arie aber begegnen wir in der Gesangspartie einem Thema, das nur als Zitat verstanden werden kann. |

|

|

|

Es ist das Hauptthema des Chores „Sind Blitze, sind Donner in Wolken verschwunden” aus der Matthäus-Passion, So erschreckend dies klingen mag, so verheißungsvoll sind die Worte, daß Christus „mit starker und helfender Hand des Todes gewaltig geschlossenes Band” zerbricht.

Darauf aber gründet sich die Sterbenszuversicht des Christen; dessen harren wir in Geduld, „bis wir einschlafen seliglich”. Das ist das Bekenntnis des vollendet schönen Choralsatzes, der das in seiner Art unvergleichliche, wahrhaft monumentale Werk beschließt.

[Of all of the cantatas by Bach that have come down to us, this is perhaps the most important/significant one. It belongs to the very last period of the master’s life. You get the impression that he, to a certain extent, was trying to sum up in this cantata all of the preceding cantatas that he had composed. The thoughts concerning the events of passion week are foremost here, as would be appropriate for the Sunday Estomihi. It is possible to recognize several instances were connections can be made to Gospel reading for this Sunday: Luke 18:31-43. The final line of the first verse in mvt. 1 points to Luke 18: 38-39, the first recitative mentions Jesus’ going to Jerusalem: Luke 18:31. These Passion-tide thoughts, however, are also related to reflections on mortality generally, because the underlying chorale text by Paul Eber is funereal. As in almost all cases of cantatas from this period in Bach’s life, the outer movements (first and last) are taken verbatim, while in the middle movements are basically paraphrased with a few exceptions were certain lines are kept as is. The dominating melody throughout, taken from a French Psalter, already appeared together with the text for the first time as early as 1562: |

|

|

|

This melody, with the note values as given above (mainly whole-tone steps in quarter notes,) is the one used by the sopranos to render the cantus firmus in movement 1 (this movement is in F major and is orchestrated for 2 recorders, 2 oboes, strings and organ.) From the first to the last bar/measure we can hear almost uninterruptedly in the orchestra and the accompanying voice parts the first line of the chorale with its note values reduced in time value by one half (per diminutionem). This is heard in quick succession, often crossing over from one part to another in quick succession while constantly changing in timbre, pitch, and key: |

|

|

|

The name of Lord Jesus Christ, who is a true hbeing and a true God, is uninterruptedly invoked. This is the name of One, who goes to Jerusalem in order to die on the cross.

This second thought, the one of Christ’s death, finds its expression by means of citing in its entirety the Passion-tide hymn “Christ, you Lamb of God” [Agnus Dei] as a second cantus firmus. This Passion-tide melody is entrusted only to the orchestra and appears in all of the three instrumental groups (the flutes, the oboes, and the strings), and, in addition, it occurs in various keys (F major and C major.) Compared to the main chorale melody (cantus firmus sung by the sopranos), this chorale [Agnus Dei] appears in note values which have been doubled in length (per augmentationem) with is main note values as half notes: |

|

|

|

In this way, this overpowering composition absolutely (in every way) becomes a double chorale. But this in itself is still not sufficient: As early as in the orchestral overture and then several times after that in the middle of the piece, a third chorale additionally appears in the basso continuo: |

|

|

|

This is the first line of the melody by Hassler which was first used in a ‘death’ chorale by Christoph Knoll with his chorale text: “Herzlich tut mich verlangen” only later to become associated with Paul Gerhardt’s chorale text “O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden, not the least of all due to the influence of Bach’s SMP to become one of the classical Passion-tide hymns. In this chorale, both the thoughts of dying and Christ’s passion have become inextricably fused together. It even appears once, in the final line of the chorale in the vocal parts: |

|

|

|

The text and the tonal atmosphere summarize everything that this profound and yet so tonally transparent composition has to say.

Leading into the paraphrased soprano aria, “Die Seele ruht in Jesu Händen” (c minor) based on the fourth verse of Eber’s chorale is a tenor recitative, condensed from the content of Eber’s second and third verses and accompanied only by a basso continuo. If you have to admit that the introductory choral movement is without equal among Bach’s compositions of this sort, then you will also be tempted to select this aria from among all Bach’s arias. The instrumental soloist here is the oboe. Both recorders are in an accompanying mode supported by short chords played on the organ, the bass notes of which are played pizzicato using ‘dabbing’ eighth notes: |

|

|

|

In these tones there is an endlessly painful longing, but also the foretaste of inexpressible peace, particularly when the soprano enters and we can hear the songlike, portato melody that takes place as a conversation between the singer and the oboe. And yet Bach has saved up the highest moment for the middle section of this aria where the tonality turns toward the major keys, at first Ab major, but then Eb major, at which point the oboe renders its truly comforting lines supported by the recorders and organ which are accompanied by a pizzicato bass. The voice expresses the longing for death, but also the joy in the face of death with the words “Ach, ruft mich bald, ihr Sterbeglocken” [“O call me soon, you funeral bells.”] We can almost believe that we are hearing them. At precisely the midpoint of this aria, the strings begin playing pizzicato, 16th-note chords. |

|

|

|

For only 4 ½ bars we hear the ringing of the bells. This (what is suggested by the ringing of these bells) is only a premonition of that state of blessedness yet to come, and the listener’s ear and heart should not indulge itself (give in to the associated feelings and thoughts) any longer than just for a few moments. But the joyful anticipation of death is overwhelming (it gushes forth) “weil mich mein Jesus wieder weckt” [“because my Jesus will awaken me again.”]

However, the reawakening of the dead also means a reawakening to face the Day of Last Judgment.

When, at that point in the future, the trumpets shall sound,

And when the construction of the world itself along with the firm fortress of Heaven

Having been smashed will disintegrate and fall down in many pieces,

In greatest of all contrasts to the previous movement, these words are sounded out for us at the beginning of the next movement, which adds to them after verses 5 and 6 from Eber’s hymn the words of Jesus as quoted from John 5:24-25 and John 8:52. When you hear the first bars of this bass recitative to which are added to the organ the strings playing throbbing chords with the addition of a solo trumpet presenting fanfares, then you can feel yourself transported back to an earlier time in Bach’s creative career. This movement is directly reminiscent of the recitative “Erschrecket, ihr verruchten Sünder,” which Bach inserted into his Weimar cantata ”Wachet, betet, betet, wachet” (BWV 70) which received a repeat performance during his first years in Leipzig. Similar to this movement composed 20 years earlier, this movement also can be divided into two contrasting halves. After the picture of horror/fright there follows immediately one of comfort. Beginning with measure 14, the recitative moves into a fixed rhythm (a tempo giusto); accompanied only by the continuo, the bass sings: |

|

|

|

Once again following the chorale text by Eber, the first line of the chorale melody from the French psalter returns once again and is also found in the basso continuo, where it continues for 7 measures. Without any clear separation, this recitative moves right on into the second aria (bass voice, trumpet, strings, organ, in C major.) Complete mastery is demonstrated by how the audaciousness of expression and the strictness of form are combined. Three times, using the threatening sounds of the instruments together with the passionate declamation of the voice, the destruction/downfall of heaven and earth are depicted, while between these sections, accompanied only by the organ, the first melody line of the chorale is once again presented just as it appeared in the ‘a tempo giusto’ section of the recitative leading into the aria. In the midpoint of this aria, however, we find in the vocal part a theme which can only be considered/understood as a citation of another work: |

|

|

|

This is the main theme of the choral section “Sind Blitze, sind Donner in Wolken verschwunden” in the SMP. As terrifying as they may sound, so promising are the words which state that Christ will break asunder “mit starker und helfender Hand des Todes gewaltig geschlossenes Band” [“with a strong and helping hand the powerfully formed bond of death.”]

Upon this is founded a Christian’s confidence regarding the nature of death, which we await patiently “bis wir einschlafen seliglich” [“until we fall asleep blissfully.”] This is the creed/confession expressed in this perfectly wrought, beautiful choral movement with which Bach concludes in his inimitable manner and incomparable, truly monumental work.]

Comments:

1. Smend wrote this commentary as notes to an actual ‘church-going’ congregation, which should account for the manner of presentation directed at his specific audience.

2. Smend’s new contributions to a discussion of BWV 127 are significant: the identification of the chorale melody. |

| |

|

W. Gillies Whittaker: “The Cantatas of Johann Sebastian Bach" |

|

[Oxford University Press, 1959] vol. 2, pp. 448-453.

In his later days, however, we find examples where he seems to be reaching out to those plastic and connected groups of movements with which Mozart achieved such miracles in his operatic finales. The splendid bass Recitativ und Arie in `Herr Jesu Christ, wahr'r Mensch und Gott' is a fine specimen. The text is a paraphrase of most of the stanzas 5–7 of P. Eber's hymn, with some lines of stanza 6 included in their original form. The music falls into seven sections—(a) 4/4, recitative accompanied by trumpet and strings, (b) 4/4, arioso secco, hymn quotation, with line 1 of the foundational chorale melody, (c) 6/8 arioso, tutti, (d) 4/4, arioso secco, further hymn-quotations and lines 1 and 2 of the melody, (e) 6/8, arioso, tutti, (f) modified form of (b), (g) modified form of (c). (a)—a picturof the Day of Judgment—`When one day the trumpets sound, and when the framework of the world together with those of heaven's strongholds shattered will fall, then remember me, my God, in favor'. The strings shudder in the customary way, the tromba rings out fanfares. At bar 3 the fanfares cease for the time being, the trumpet joins in the trembling and resumes the fanfare on the last word. The tutti shuddering becomes less frequent during `When Thy servant one day before the Judgment seat stands, there thoughts themselves accuse' (see Romans ii. 15) `so may Thou alone', and normal again for one bar with a longer rest before a group in the next, in `Oh Jesus, my pleader be, and to my soul comfortingly say'. Though the signature is one flat, no key is defined; the opening first inversion of the chord of G major is followed by the last inversion of a seventh on C, the keys of D minor, A minor, G minor, and C minor lead to two diminished sevenths and finally to the key of G minor. This restlessness and lack of tonal center form a fine contrast to the stability of the next section, which is joined to (a) by a tender little duet for the violins; (b)—' Furwahr, fürwahr, euch sage ich' (` Verily, verily, to you say I', see St. Matthew xxiv. 34); line I of the chorale comes thrice in the vocal part, once completely and once partially in the continuo. The main key is F, leading eventually to C; (c)—the text is a version of the remainder of the Savior’s saying, St. Matthew xxiv. 34, 35—` When heaven and earth in fire disappear, yet shall then a believer eternally endure.' The key signature is deleted. The trumpet peals a fanfare, string demisemiquaver arpeggi tearing down paint the cataclysm, upward bassi slides the roaring of the flames of fire, and quaver chords for tromba and upper strings the crackling. 'Bestehen' ('endure') of course sustains while the conflagration surrounds the believer; (d) 'Er wird nicht kommen in's Gericht und den Tod ewig schmecken nicht' (` He will not come to the judgment And the death eternally taste not'). The lines are sung respectively to 1 and 2 of the chorale melody. The much-extended music of the added text curves gracefully—'nur halte dich, mein Kind, an mich' ('only hold thyself, my child, to me'). Line 1 forms a quasi-ground-bass, heard nine times in all, with two interpolated fragments, the comforting assurance is promised instrumentally over and over again; (e)—`ich breche mit starker und helfender Hand des Todes gewaltig geschlossenes Band' ('I break with strong and succoring hand the death's powerfully closed bond'). String demisemiquavers resume, but in a different form, the tromba grimly repeats a powerful rhythm. The two closing bars to `Band' are practically the same as those corresponding in (c) to ` bestehen'. There is a surprising thing in the vocal line. With the exception of the one note required by `Hand' and `Band' in the one case as against the two needed for `-schwunden' in the other (` Sind Blitze, sind Donner in Wolken verschwunden'), the solo part is identical with the four choral entries of the `Thunder and lightning' chorus of the St. Matthew Passion ! It is no mere fortuitous reminiscence, for the entries in the chorus are not in regular fugal order, but in each case at the fourth above. It is a unique case of self-quotation. Why did Bach borrow an isolated idea for a middle section of a number written some ten or eleven years later? The moods are certainly somewhat akin, in the earlier work rage at the enemies of the Savior, in the later the breaking asunder of the bonds of death; but though there are many cases of parallel moods there is no other of borrowing like this; (f)—the section is condensed to five bars, the number of entries of the melody are two vocal and one instrumental. (c) made an extensive modulation to the dominant; in (g) this is reduced to a single bar and the material otherwise slightly altered. The verbal clause is sung once only, and then the orchestra ends with an abrupt quaver C major chord.

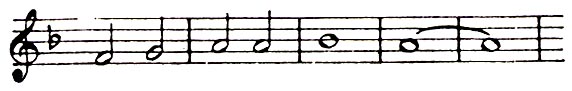

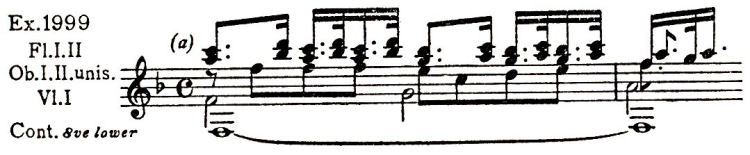

The cantata is short, five numbers only, a commendable condensation of the eight stanzas of the hymn. The three larger numbers are of superb quality, producing a work of the highest order. The Gospel for Quinquagesima, the Sunday before Lent, is St. Luke xviii. 31-43, `Behold, we go up to Jerusalem. . . . For he shall be delivered unto the Gentiles, and shall be mocked, and spitefully entreated, and spitted on; and they shall scourge him and put him to death.' In the 1724 (?) cantata for the same Sunday, No. 23, Bach introduced the pre-Reformation melody of the Agnus Dei into the accompaniment of the opening duet, and the German hymn form of three verses is the text of the last chorus, the melody coming with each stanza. In i of No. 127 the Agnus Dei is heard orchestrally, and, as well, the melody of the foundational hymn—L. Bourgeois's ‘On a beau son maison bastir'—is used in the normal manner. This is the only case in which two hymn-melodies are brought together in one number. There is another interesting fact. The last number of No. 23 concluded the first version of the St. John Passion, so that No. 127 is linked up with both of the great Passions. The fantasia is one of the most superb in the whole series, exquisite in its beauty, expressiveness, and tenderness, masterly to the highest degree in its technical construction. Above a three-bar tonic pedal three all-embracing motives make their appearance simultaneously. Line 1 of the Agnus Dei is played by the upper strings in minims and semibreves, a quaver version of line 1 of the chorale (this term is used here as referring to `Herr Jesu Christ' and not to the Agnus Dei) for unison oboes, and an independent waving figure for the two flutes: |

|

|

|

No other derivative is employed; it accompanies every line of the canto fermo, its innumerable repetitions keep perpetually before our eyes the Sufferer to Whom the prayer is uttered. In all cases where it is heard in the three instrumental groups—flutes, oboes, and upper strings—except where the strings play it in canon, the group is in unison, to make it prominent in the texture. In bar 3 the flutes take up the derivative, in bar 4 the oboes again, in 5 the bassi, in 6 the upper strings, in 7 the flutes. All the upper instruments share in (a); it is never found in the continuo and there is only one reference later in the voices. A two-note idea— (8th note rest) eighth-note —(b), the only other recurring motive, is heard in the two lower string lines. At bar 9 the bassi settle on the dominant for another three-bar pedal, line 1 of the Agnus Dei is played by oboes and violas, the derivative by flutes and in bar 11 by upper strings. (a) is present in every bar of the fantasia in some form or other; there is no need to mention each appearance. After the second pedal the derivative, successively in flutes, continuo, upper strings, oboes, modulates through G minor to the gloomy F minor, which key continues until the voices begin in F major. In the bar before this, (a) comes in scalic form, a version which is heard several times afterwards. A threefold canon on the derivative in the lower voices prefaces and accompanies the first bar of the canto; during bars 2 and 3 the theme is heard successively in flutes, altos and tenors in sixths, while the basses tenderly breathe `wahr'r Mensch und Gott' ('true man and God'), with a rest in the middle, to (b). Before the line is finished the flutes begin the derivative, and then the lower voices repeat `wahr'r Mensch und Gott'. In the interlude the derivative is heard in turn in upper strings, oboes, and flutes, and the scalic version of (a) is prominent. Line 2 is `Thou Who sufferest martyrdom, anguish and mockery'; the scalic idea continues, the derivative comes in altos and basses, syncopations stress `Who' and `martyrdom', `anguish and' has an expressive two-note figure. The threefold canon is repeated at the end. During the ritornello flutes and oboes twice play the derivative alternately while unison upper strings play

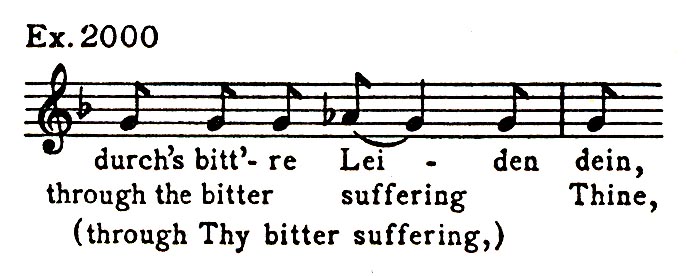

four times on one note, emphasizing the beginning of line 1, and in each case the bassi pnotes 5, 6, and 7, followed by a drop of a fifth instead of a rise of a second. Line 3—` For me on the cross and at last died'—modulates from F to C minor and F minor; the bass entry of the derivative brings `died' on a gloomy Ab while the altos leap up to C on `cross'. A twofold canon on the derivative opens the alto and tenor lines, oboes follow the basses in canon, but at the octave instead of the fourth or fifth, notes 4-6, G E F, making a poignant dissonance above the bass Ab. The basses sing the final derivative of the section: the last interval, a solemn seventh on `died', falling to the dominant instead of rising a second. This introduces a dominant pedal above which the second line of the Agnus Dei begins in the flutes, the derivative accompanying each bar. In A minor the derivative mounts from the bassi to upper strings and then to oboes, the latter beginning tellingly on high C. Line 2 of the Agnus Dei—` Thou that bearest the sins of the world'—acts as upper strings counterpoint to line 4 of the hymn—'And for me Thy Father's favor earned'—not a mere example of technical skill, but a striking means of reinforcement of the significance of one hymn by an instrumental quotation from another. The bassi use (b); the line is accompanied by a fourfold entry of the derivative, flutes, altos at the fourth below, oboes at the ninth above, bassi at the ninth below. The latter two introduce a new version, to be heard often later, the fourth note dropping a third instead of a second. With this form the basses close the section. It is now presented as a canon at the sixth between upper strings and oboes, the original appears in bassi, upper strings, and flutes, the last named beginning tensely with almost the highest note possible in the older form of the instrument, F. (b) comes in the continuo and upper strings, (a) is mostly scalewise. Line 5—'I beg through the bitter suffering'—is exceptionally beautiful. The three lower voices enter in turn before the canto with the second version of the derivative. As a countersubject, first in unison flutes, then in both orchestra and choir, a sorrow-laden derivative of the derivative is heard: four times on one note, emphasizing the beginning of line 1, and in each case the bassi pnotes 5, 6, and 7, followed by a drop of a fifth instead of a rise of a second. Line 3—` For me on the cross and at last died'—modulates from F to C minor and F minor; the bass entry of the derivative brings `died' on a gloomy Ab while the altos leap up to C on `cross'. A twofold canon on the derivative opens the alto and tenor lines, oboes follow the basses in canon, but at the octave instead of the fourth or fifth, notes 4-6, G E F, making a poignant dissonance above the bass Ab. The basses sing the final derivative of the section: the last interval, a solemn seventh on `died', falling to the dominant instead of rising a second. This introduces a dominant pedal above which the second line of the Agnus Dei begins in the flutes, the derivative accompanying each bar. In A minor the derivative mounts from the bassi to upper strings and then to oboes, the latter beginning tellingly on high C. Line 2 of the Agnus Dei—` Thou that bearest the sins of the world'—acts as upper strings counterpoint to line 4 of the hymn—'And for me Thy Father's favor earned'—not a mere example of technical skill, but a striking means of reinforcement of the significance of one hymn by an instrumental quotation from another. The bassi use (b); the line is accompanied by a fourfold entry of the derivative, flutes, altos at the fourth below, oboes at the ninth above, bassi at the ninth below. The latter two introduce a new version, to be heard often later, the fourth note dropping a third instead of a second. With this form the basses close the section. It is now presented as a canon at the sixth between upper strings and oboes, the original appears in bassi, upper strings, and flutes, the last named beginning tensely with almost the highest note possible in the older form of the instrument, F. (b) comes in the continuo and upper strings, (a) is mostly scalewise. Line 5—'I beg through the bitter suffering'—is exceptionally beautiful. The three lower voices enter in turn before the canto with the second version of the derivative. As a countersubject, first in unison flutes, then in both orchestra and choir, a sorrow-laden derivative of the derivative is heard: |

|

Ex.2000 |

|

|

|

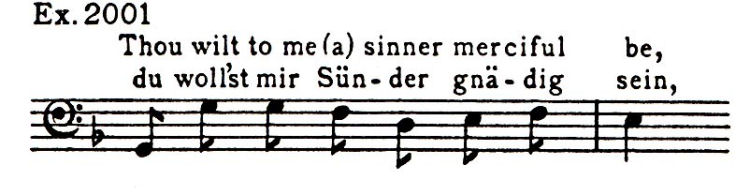

The upper strings play short wailing phrases, the bassi punctuate with the version of the last notes which drops a fifth. Beginning in bar 2 of the canto the basses climb chromatically to high Eb, `beg' and `through' being separated by a rest, the continuo follows the same outline but to the time-pattern of (b), the countersubject comes in oboes and flutes, and the altos sing a phrase of much pathos. The basses conclude with the derivative. The vocal section ends in C minor, and before the last line—`Thou wilt to me (a) sinner merciful be!'—begins in the same key, the ritornello modulates through G minor and D minor, the derivative appearing successively in upper strings, flutes, bassi, upper strings, flutes. The line is mostly supported by a pedal, the upper strings utilize (b), altos and tenors sing the derivative in canon, and then basses and flutes again introduce the second version in a threefold canon, at the octave above and the fifth below. The chorale begins in F and finishes in C, and in the tutti version at the close of the cantata is it distinctly harmonized so. In the fantasia the canto line moves from C minor to C major, but during the sustained note F is reverted to, and the choir ends unexpectedly on the dominant. Dovetailing with this, line 3 of the Agnus Dei begins in unison upper strings, with the second derivative in continuo, oboes, and flutes, the last-named again beginning on high F, modulating through D minor and C back to F. Instead of the Latin melody ending normally on the tonic, there is a quaver rest, and its final note coincides with a most beautiful form of the second derivative, the key changing to Bb minor, and the last part of the phrase drops, like the bassi version, a fifth. The four voices, entering in succession, form a coda out of another version of the second derivative, beginning with an upward leap of an octave or seventh instead of a repeated note:

Ex. 2001

|

|

|

|

so bringing confidently into prominence the word `woll'st'. Sadness is mingled with happiness, the redeemed one cannot forget that the Christ is suffering for him. F minor prevails until the last chord, when F major blazes out in a sudden realization that the fervid prayer will be answered. |

| |

|

Alfred Dürr: "Johann Sebastian Bach: Die Kantaten“ |

|

[Bärenreiter, 1971, 1995] pp. 285-288

Herr Jesu Christ, wahr' Mensch und Gott • BWV 127

NBA I/8.1, 107 — AD: ca. 21 Min. key / time signature

[CHORAL. S (+ Trba ?), A, T, B, Flauto dolce I,II,

Ob I,II, Str, Bc]

F C

Herr Jesu Christ, wahr' Mensch und Gott,

Der du littst Marter, Angst und Spott,

Für mich am Kreuz auch endlich starbst

Und mir deins Vaters Huld erwarbst,

Ich bitt durchs bittre Leiden dein:

Du wollst mir Sünder gnädig sein.

RECITATIVO [T, Bc]

B—F C

Wenn alles sich zur letzten Zeit entsetzet,

Und wenn ein kalter Todesschweiß

Die schon erstarrten Glieder netzet,

Wenn meine Zunge nichts, als nur durch Seufzer spricht

Und dieses Herze bricht:

Genung, daß da der Glaube weiß,

Daß Jesus bei mir steht,

Der mit Geduld zu seinem Leiden geht

Und diesen schweren Weg auch mich geleitet

Und mir die Ruhe zubereitet.

ARIA [S, Fld I, II, Ob I, Str, Bc] c C

Die Seele ruht in Jesu Händen,

Wenn Erde diesen Leib bedeckt.

Ach ruft mich bald, ihr Sterbeglocken,

Ich bin zum Sterben unerschrocken,

Weil mich mein Jesus wieder weckt.

RECITATIVO + ARIA [B, Trba, Str, Bc] C C

Wenn einstens die Posaunen schallen,

Und wenn der Bau der Welt

Nebst denen Himmelsfesten

Zerschmettert wird zerfallen,

So denke mein, mein Gott, im besten;

Wenn sich dein Knecht einst vors Gerichte stellt,

Da die Gedanken sich verklagen,

So wollest du allein,

O Jesu, mein Fürsprecher sein Und meiner Seele tröstlich sagen:

Fürwahr, fürwahr, euch sage ich:

Wenn Himmel und Erde im Feuer vergehen,

So soll doch ein Gläubiger ewig bestehen.

Er wird nicht kommen ins Gericht

Und den Tod ewig schmecken nicht.

Nur halte dich,

Mein Kind, an mich:

Ich breche mit starker und helfender Hand

Des Todes gewaltig geschlossenes Band.

CHORAL [S, A, T, B, Bc (+ Trba ?, Fld I, I in 8", Ob I, II, Str)] F C

Ach, Herr, vergib all unser Schuld;

Hilf, daß wir warten mit Geduld,

Bis unser Stündlein kömmt herbei,

Auch unser Glaub stets wacker sei,

Dein'm Wort zu trauen festiglich,

Bis wir einschlafen seliglich.

Diese Choralkantate erklang erstmals am 11. Februar 1725. Als Text liegt ihr das achtstrophige Kirchenlied von Paul Eber (1562) zugrunde, dessen Anfangs- und Schlußstrophe wörtlich übernommen wurden, während die übrigen sechs Strophen zu Arien und Rezitativen umgeformt wurden. Die Strophen 2 und 3 wurden dabei zum ersten Rezitativ, Strophe 4 zur ersten Arie (Satz 3), Strophe 5 zum zweiten Rezitativ (Satz 4, erster Teil), die Strophen 6—7 zur zweiten Arie (Satz 4, zweiter Teil) umgedichtet. Wer diese textliche Umformung vorgenommen hat, ist nicht bekannt.

Inhaltlich war Ebers Gedicht, wenngleich ein Sterbelied, zur Verwendung am Sonntag Estomihi nicht ungeeignet. Die Eingangsstrophe mit ihrem Hinweis auf Jesu Passion und Kreuzestod schließt sich an die Leidensverkündigung des Evangeliums an; die Schlußzeile der Eingangsstrophe, »Du wollst mir Sünder gnädig sein« erinnert an den Ruf des Blinden um Erbarmen (Luk. 18, 38-39). Die weiteren Strophen gehen mit ihren Sterbegedanken dann freilich eigene Wege; sie bitten Jesus, er möge sich auch, wenn der eigene Tod kommt, als Retter erweisen und den Gläubigen aus dem Gericht nehmen — ein Gedankengang, der gerade in der Barockdichtung immer wieder anklingt und dessen Bindeglied zum Sonntagsevangelium im ersten Rezitativ ausgesprochen wird: »der Glaube weiß, daß Jesus bei mir steht, der mit Geduld zu seinem Leiden geht und diesen schweren Weg auch mich geleitet«. Mit andern Worten: Mit Jesu Gang nach Jerusalem beginnt sich sein Heilswerk zu erfüllen und damit auch die eigene Hoffnung auf ein seEnde.

Bachs Komposition ist bestrebt, die aufgezeigten Verbindungen des Liedes zum Evangelium des Sonntags noch weiter zu verdeutlichen. Die Einleitungssinfonie und die Zwischenspiele des großangelegten Chorsatzes über die erste Liedstrophe kombinieren die Anfangszeile des Liedes, die, rhythmisch verkürzt, von den einzelnen Instrumentengruppen ständig einander zugespielt wird, mit der in langen Notenwerten (zunächst von den Streichern, später auch von den Oboen und Blockflöten) vorgetragenen Liedweise >Christe, du Lamm Gottes<. Auch diese Weise ist wiederum in doppeltem Sinne beziehungsvoll, einmal als Hinweis auf Christi Passion, zum andern als die auch von dem Blinden des Evangelientextes ausgerufene Bitte um Erbarmen. Endlich verleihen auch die Instrumentierung des Satzes mit Blockflöten sowie der gleichbleibende punktierte Rhythmus dem Satz eine demütig flehende Gebärde.

Ein schlichtes Rezitativ leitet über zur ersten Arie, deren erlesene Instrumentation bei Bach sonst nirgendwo anzutreffen ist: Eine Solo-Oboe konzertiert vor dem Hintergrund kurzer Flötenakkorde; auf das Stichwort »Sterbeglocken« im Mittelteil des Satzes setzen dann die gezupften Streichinstrumente mit einer Glockenimitation ein.

Der nachfolgende Satz entwirft ein drastisches Bild des Weltgerichts. Zum Streicherchor tritt die Trompete, erstmals auf das Textwort »Wenn einstens die Posaunen schallen«, als charakteristisches Instrument zur Kennzeichnung des Jüngsten Tages. Die Form ist außergewöhnlich. Ein instrumentenbegleitetes Rezitativ geht unmittelbar in eine Arie über, der das übliche Ritornell fehlt und die statt dessen durch den ständigen Wechsel zwischen continuobegleiteten und vollinstrumentierten Teilen der Rondoform angenähert ist. Die Anregung zur formalen Gestaltung dieser Arie mag der inhaltliche Kontrast zwischen der Vernichtung von Himmel und Erde und der Sicherheit der Gläubigen am Ende der Zeiten gegeben haben. Dabei treten auf die nahezu wörtlich aus der Lieddichtung Ebers entnommenen Zeilen »Fürwahr, fürwahr, euch sage ich« und »Er wird nicht kommen ins Gericht« auch Melodiezitate des Chorals auf, die hier als Symbol der von Christus gegründeten Kirche zu verstehen sind und die Sicherheit der Gläubigen bezeugen.

Ein schlicht-vierstimmiger Choralsatz beendet die Kantate. Doch selbst in diesem einfachen Satz erweist sich Bach als ein Meister der Charakteristik, so z. B. wenn die Zeile »auch unser Glaub stets wacker sei« durch besondere Beweglichkeit der Begleitstimmen ausgezeichnet ist oder wenn die Worte »bis wir einschlafen« durch kunstvolle Harmonisierung hervorgehoben werden.

[This chorale cantata received its first performance on February 11, 1725. The text is based upon the eight verses of a chorale text by Paul Eber (1562), of which the first and last verses were incorporated verbatim, while the remaining six verses were transformed into arias and recitatives. In the process, paraphrases of verses 2 and 3 were paraphrased in the first recitative, verse 4 in the first aria (movement 3,) verse 5 in the second recitative (first part of movement 4,) and verses 6 and 7 in the second aria (second part of movement 4.) It is not known who undertook this transformation of the original chorale text.

The content of Eber’s poem (chorale text), even though it is a funeral hymn, is not inappropriate for use on the Sunday called Estomihi. The introductory verse with its reference to the passion of Jesus and his death on the cross is connected to the Gospel’s announcement/prophecy regarding the suffering to take place. The final line of the first verse brings to mind the blindman’s cry for compassion/pity (Luke 18: 38-39): “Be merciful unto me, a sinner.” The other verses, to be sure, go their own way with their thoughts about death; they ask Jesus, when the individual dies, to show himself as the savior and remove the believer from the Final Judgment – a sequence of thoughts frequently expressed particularly in Baroque poetry and which establishes the connection to the Gospel reading for this Sunday by stating in the first recitative: “the [my] belief knows securely that Jesus, who patiently goes to face his suffering, stands by me and leads me along this difficult path.” In other words: at the moment when Jesus goes up to Jerusalem, the fulfillment of his task to heal/save (mankind) is beginning and with it there begins also the hope for a blessed end (death) on the part of each believer. Bach’s composition endeavors to clarify even more these connections that the chorale has with this particular Sunday’s Gospel reading. The introductory sinfonia and the interludes of the large-scale choral movement based upon the first verse of the chorale combine the first line of the melody which, in its rhythmically shortened form is passed off, back and forth, from one instrumental group to another over and over again, together with the presentation in long note values, played at first by the strings, then later also by the oboes and recorders, of the chorale “Christ, you Lamb of God” [Agnus Dei.] This melody has a twofold significance: it points to Christ’s passion, but it also makes the connection to the request for mercy uttered by the blind man. Finally, the orchestration of this movement using recorders that maintain an invariable dotted rhythm adds to this movement a humbly imploring gesture.

A plain recitative forms the bridge to the first aria, the exquisite instrumentation of which is not to be found anywhere else in Bach’s oeuvre: a solo oboe plays in a concertizing manner before a background of short chords played by the recorders; then, when the key word “Sterbeglocken” [‘funeral bells’] appears in the middle section of the movement, the pizzicato strings begin to play an imitation of these bells.

The following movement depicts a drastic image/scene of the Day of Last Judgment. A trumpet, the instrument which characteristically marks the Day of Last Judgment, appears for the first time at the words “When the trumpets shall sound.” The form of this movement is extraordinary: an instrumentally accompanied recitative merges directly into an aria which lacks the customary ritornello and in place of it has what approaches a rondo form through the use of a continuous alternation between sections having only continuo accompaniment versus others that have full instrumentation. The formal structure of this aria was perhaps suggested by the text content which contrasts in these end times the destruction of heaven and earth with the security felt by a believer. In the course of this movement while certain lines are quoted almost directly from Eber’s text: “Fürwahr, fürwahr, euch sage ich” [“Verily, verily I say unto you”] and “Er wird nicht kommen ins Gericht” [“he will not be judged”], there appear, taken from the main chorale melody, quotations which can be understood to symbolically represent the church established by Christ and which testify for the certainty that a believer can experience.

An unpretentious, 4-part chorale movement ends this cantata. Yet even in this simple setting Bach demonstrates his mastery of characterization, i.e., when the line “auch unser Glaub stets wacker sei” [“that our belief remain constantly vigilant/courageous”] is distinguished musically by a particular mobility of the accompanying voices or when the words “bis wir einschlafen” [“until we fall asleep”] is brought out/emphasized by means of a very artistic harmonization.

Comments:

1. Dürr neglects to point out Smend’s discovery of Bach’s use of the chorale melody for “O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden” etc. in the bc and bass voice.

2. Uncharacteristically, Dürr, in his discussion of movement 1, does not comment much on the structure of this movement. In other cantata discussions, such a discussion would be in great detail and take up most of the space devoted to a single cantata.

3. Otherwise Dürr’s discussion of the theological and textual connections with the music itself is one of the most important in this area (compared to those of other commentators.)

4. Dürr gives the discussion of the soprano aria rather short shrift (again compared to other commwho waxed poetic over this very beautiful movement.) |

| |

|

Alec Robertson: “The Church Cantatas of J. S. Bach” |

|

[Cassell, London, 1972] pp. 95-96

Herr Jesu Christ, wahr'r Mensch und Gott (Lord Jesus Christ, true man and God).

Chorale Cantata BWV 127. Leipzig, 1725.

The libretto has verses i and viii of Paul Eber's hymn with the above title in Nos. 1 and 5; the rest are paraphrased. The melody in Nos. 1, 4. and 5 is Louis Bourgeois' 'On a beau sa maison bastir'

1 CHORUS

(As above)

SATB. Fl i, ii, Ob i, ii, Vln i, ii, Vla, Cont

A remarkable feature of this movement is Bach's simultaneous use of the opening phrases of the chorale and the Lutheran version of the plainsong Agnus Dei which comes at the end of the Litany of Loretto and which Bach also uses in Cantata BWV 23. These are heard in the first four bars, over a pedal bass, on oboes, violins and violas respectively, with a dotted rhythmic figure on the flutes above.

The words of the chorale, which concentrate on the sufferings of Christ, mocked, spat on, scourged and at last crucified, explain Bach's use of these motifs.

No sermon on the Passion could be as moving, as eloquent as this wonderful movement.

2 RECITATIVE

`Wenn alles sich zur letzten Zeit entsetzet, und wenn ein kalter Todesschweiß die schon erstarrten Glieder netzet' (When all at the last hour shudders, and when a cold death-sweat moistens the already stiffened limbs')

T. Cont

`The contemplation of Christ's agony breaks my heart, but faith tells me that Jesus is with me and His sufferings prepare for my rest'.

3 ARIA

`Die Seele ruht in Jesu Händen, wenn Erde diesen Leib bedeckt' ('The soul rests in Jesu's hands when earth this body covers') S. Fl i, ii, Ob i, VIn i, ii, Vla, Cont

Below the slow procession of quavers, staccato on the flutes, the oboe sings the beautiful melody of rest, the string basses having pizzicato quavers. The middle section has broken phrases for the voice with the orchestra illustrating the line 'Ah, call me soon ye death-bells'. The singer continually repeats the words `I am at death unaffrighted because my Jesus me awakens'. Whittaker suggests the opposite is the case, which may be so. I am reminded of Orestes's aria in Gluck's Iphigenia when the orchestra—in this case—contradicts his assertion, `My heart is calm within my breast'.

RECITATIVE AND ARIA

'Wenn einstens die Posaunen schallen' ('When one day the trumpet sounds')

B. Tr, Vln i, ii, Vla, Cont

This dramatic movement is divided into seven sections, the third of which is a vivid picture of the Last Judgment. The trumpets ring out in Nos. I, 3 and 7. No. 2 quotes St Matthew XXIV. 34. `Beware I say unto you', to quiet music, quoting the first line of the chorale. After No. 3, `when heaven and earth in fire disappear, yet shall a believer eternally endure'. No. 4 quietens again to reassure the soul that it will not die eternally, No. 5 adds to this, in powerful phrases, that Christ will break death's enclosing hand. Nos. 2 and 3 are then repeated.

CHORALE

'Ach Herr, vergieb all unsre Schuld, hilf, dass wir warten mit Geduld' ('Ah, Lord, forgive all our guilt, help that we wait in patience')

SATB. As No. 1, with voices, Cont

The sixth verse of the chorale.

[End of Robertson’s commentary]

Comment:

1. A rather straightforward, succinct commentary with very little that is new.

2. Robertson does not include anything at all about Smend’s discovery of the untexted “O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden” discovered 24 years earlier. |

| |

|

Ludwig Finscher: Commentary to Harnoncourt/Leonhardt Complete Cantata Series on Teldec |

|

(1982)

Herr Jesu Christ, wahr' Mensch und Gott (BWV127), written for Quinquagesima Sunday 1725 (February 11) provides a commentary on the Gospel for that Sunday, Christ's prophecy of His Passion and Resurrection and the healing of the blind man (Luke 18), in a hymn by Paul Eber which is actually a funeral hymn. Bach stresses its relevance to Passion and Resurrection by superimposing a number of symbols in the orchestral writing of the opening chorus: recorders as mourning instruments, dotted rhythms representing mourning (or scourging), the insistent repetition of the first line of the hymn, containing the key ideas "Herr", "Mensch", "Gott" (Lord, Man, God), and — mainly in the violins — the use of the chorale "Christe, du Lamm Gottes" (Christ, Thou Lamb of God). After a recitative, paraphrasing verses 2 and 3 of the hymn, there follows an equally unusual soprano aria in which the staccato chords of the recorders and the figures in the oboe played concertante with the voice each express transcendence in its own way ("Die Seele ruht in Jesu Händen" — My soul will rest in Jesus' keeping), while the pizzicato of the basses, which runs through the whole aria, is revealed in the middle section as the sound of the death knell (strings). In strong contrast, there follows a representation of the Last Judgment which is quite exceptional in Bach's works. An accompanied recitative, in which the trumpet acts as the last trump, [this quaint mistranslation by an unnamed individual should read: “in which the trumpet functions/represents the trumpet that sounds on the Day of the Last Judgment”] leads into the comforting words of Jesus set in a pattern in which a passage of chorale recitative, accompanied only by the continuo, alternates with a verse of aria with strings and trumpet. By virtue of the fact that the chorale recitative consists entirely of repetitions and variants of the first line of the hymn tune, which has already been all-pervading in the opening chorus, the text of this line is again brought continually to our attention, the dramatic impact of the Last Judgment and its exegetic profundity being inextricably interwoven. The final chorale begins simply, but ends with a setting of the last line "bis wir einschlafen seliglich" (until we come to Thee above) which is as bold as it is vivid.

End of commentary by Ludwig Finscher (1982) [included as notes to the Harnoncourt/Leonhardt complete cantata series]

Comments:

1. Recorders as ‘mourning’ instruments? Where are there some good examples of this?

2. ‘Dotted rhythms representing mourning (or scourging)’ is a notion that needs to clarified: are the interval jumps large or small, are they played staccato or slurred? |

| |

|

Eric Chafe: Section on the SMP in “Tonal Allegory in the Vocal Music of J. S. Bach” |

|

[University of California, 1991] p. 421

Many performances of "Erbarm es, Gott" pass over this great tonal event in favor of emphasizing the dotted rhythm that supposedly represents the scourging. This kind of performance is testimony to our loss of the sense of tonal allegory along with the religious as opposed to purely dramatic motivation for such outstanding musical events. In fact, the dotted rhythm itself is transformed at the end of this movement, so that no hint of aggressive character is retained when it reappears in the aria that follows. "Können Tränen." Dotted rhythms remain a conspicuous presence throughout the next aria, "Komm, susses Kreuz," where they combine with the viola da gamba sound and the allemande style to suggest something of a French character after the trial. This detail was quite possibly intended as a counterpart to the pre-trial intensity of the Italian concerto style in "Erbarme dich" and "Gebt mir meinen Jesum wider," a stilling of Gewissensangst." In "Erbarm es, Gott" and "Können Tränen" the dotted rhythm mediates between the physical events and their meditative significance, its changing character one of the signs of the coming reconciliation. (The St. John Passion, too, has a sense of rhythmic reconciliation at the point of meditation on the scourging. The rhythm of the rainbow figures in the aria ''Erwäge" relate to the ostinato-like ‘kreuzige’ figure of the most agitated turbae of the Herzstück, underscoring the meaning of the cross as the sign of reconciliation under the new covenant.)

p. 165-166

The keys of C minor and major presented in a structural relationship, as they are in Cantatas 12, 20, and 21, can be used to signify the divided worlds—human/ divine, flesh/spirit, and so on—that are unitedin the person of Christ. This idea extended to the contemplation of eternity in Cantata 20 is developed further in another chorale cantata, "Herr Jesu Christ, wahr' Mensch und Gott" (BWV 127, for Quinquagesima Sunday 1725). As befits the dualism in its title, the separation of minor and major by means of toni intermedii is far less great in this work. Like Cantata 20, "Herr Jesu Christ" presents the two Christus keys as minor and major dominants of an F major tonic.

In the opening chorale fantasia Bach uniquely combines two entire chorale melodies: "Christe, du Lamm Gottes" (Dorian G) in the woodwinds and "Herr Jesu Christ, wahr' Mensch und Gott" (the principal chorale of the work, beginning in F Ionian, but ending in C Ionian). The latter is heard as soprano cantus firmus, but diminutions of its first line pervade the other parts as well. Smend [Friedrich Smend, “Joh. Seb. Bach: Kirchen-Kantaten,” 2nd ed., 6 vols. {Berlin, 1950}, 6:42] has detected the first line of yet a third chorale—the Phrygian "Herzlich tut mich verlangen"—at six points in the bass in various transpositions.' This chorale with its associations of both death and the Passion ("Herzlich" is a funeral hymn, but the chorale "O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden" was sung to the same melody) provided Bach with an ideal means of emphasizing the dualisms of God and man, the relationship of individual death to Christ's cross and Passion. As is evident in countless compositions, Bach's interpretation of the modal characters of his chosen chorales influences his tonal planning and harmonic-tonal devices. Thus, near the close of the chorale fantasia, as "Herr Jesu Christ" comes to an end, it seems as if the movement will end in C major. Its C Ionian final phrase is preceded by a G Phrygian (C minor) appearance of "Herzlich" in the bass (mm. 65-71), after which the final line of "Herr Jesu Christ"—"du wollst mir Sünder gnädig sein"—brightens the tonality. A nine-bar postlude, however, introduces the last reference to "Herzlich" in C Phrygian (F minor), turning the final cadence to an F major so darkened by flats that it is almost a tonal catabasis. The ensuing recitative links the individual's thoughts on death to the path cleared by Jesus' stoic undergoing of the Passion, closing with an F cadence whose preparation is a cadence to B flat minor ("und diesen schweren Weg auch mich geleitet") and the Neapolitan sixth chord, G flat ("und mir die Ruhe zubereitet"). The C minor "sleep" aria follows, with its first line, "Die Seele ruht in Jesu Händen," recalling the B flat minor aria "In deine Hände" that is the tonal nadir of the "Actus Tragicus." The following recitative/ aria/chorale complex centers around a vision of the final awakening that recalls the C major of Cantata BWV 21 and, even more so, that of Cantata BWV 20, with its apocalyptic trumpet calls. Following this unusual hybrid form that is worthy of much closer study than we can give it here, the final choral setting of the last verse of "Herr Jesu Christ" completes the tendency suggested in the opening chorus and brought out in the relationship of the two arias: it closes on a C major chord ("bis wir einschlafen seliglich") after a C minor preparation; the effect intended and achieved is a final brightening in combination with a sense of both incompleteness and expectation.

The tonal plans of Cantatas BWV 20 and 127 both recall that of the "Actus Tragicus": that is, they all move from the major tonic down to the flat or minor dominant and return to the tonic with greater emphasis on major keys and at least a touching of the major dominant along the way. The emphasis on the polarizing (Cantata BWV 20) or juxtaposing (Cantata 127) of the latter keys adds a dimension of antithesis and transformation that is realized more in motivic-referential than in tonal terms in the earlier work. But the theological ideas that are referred to in the "Actus Tragicus" are so central to Bach's church work in general that we find them in other works whose structures are not as fully planned. This is especially true of the cantatas for Sundays in which the theology of death plays an important part, such as the sixteenth Sunday after Trinity, the feast of the Purification, and the third Sunday in Epiphany. In all four cantatas for the last-named occasion the question of will—God's and man's—predominates. This was, of course, the subject of Luther's famous debate with Erasmus, prompting the writing of what he considered his “best theological work,” The Bondage of the Will. |

| |

|

Eric Chafe: “Analyzing Bach Cantatas” |

|

[Oxford University Press, 2000] p. 158

Cantata 127, "Herr Jesu Christ, wahr'r Mensch und Gott," whose theological character has been thoroughly investigated by Lothar and Renate Steiger, centers on a chorale that shifts to the dominant on its final phrase—that is, from F to C. [“Sehet! Wir gehn hinauf gen Jerusalem”: Johann Sebastian Bachs Kantaten auf den Sonntag Estomihi” (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1992.)] But since in the final verse of the chorale that line ("bis wir einschlafen seliglich") refers to the concept of the "sleep of death;" Bach colors the tonality substantially with harmonies from the minor mode —that is, C minor. And he extends the C minor/major dualism to the juxtaposition of the cantata's only two arias, the first, "Die Seele ruht in Jesu Händen," in C minor and the second, "Wenn einstens die Posaunen schallen;" ending in C major, a tonal juxtaposition that mirrors the opposition of death and resurrection.

But striking as these dualisms are, it is in the opening movement of Cantata 127 that Bach makes his most detailed statement regarding the complex of ideas in the work as a whole and their relationship to the incarnation—that is, the dual natures of Jesus as "wahr'r Mensch und Gott." In that movement Bach, for the only time in his cantatas, combines two complete chorale melodies simultaneously, "Herr Jesu Christ, wahr'r Mensch und Gott;" texted in the chorus, and "Christe, du Lamm Gottes;" untexted in the various instrumental groups (strings first, then oboes, later flutes, and, finally, strings again). Although "Christe, du Lamm Gottes" enters at the beginning of the ritornello, it is "Herr Jesu Christ" that provides the motivic material for the movement. The presence of two chorales relates, of course, to the fact that the Gospel for Quinquagesima Sunday not only anticipated the Passion, to which the German Agnus Dei, "Christe, du Lamm Gottes," relates, but also described Jesus' healing a blind man along the way to Jerusalem. Recognizing Jesus' divinity, the blind man addressed Him as "true man and God"; hence the chorale that meditates on that event. The blind man also recognized his own sinfulness, however, and to bring that quality out all the more Bach introduced the first phrase of yet a third chorale melody—that of "Herzlich tut mich verlangen"—at six points in the basso continuo. Although that phrase is untexted, Bach must have associated the melody in this instance not with "Herzlich tut mich verlangen," but with "Ach Herr, mich armen Sünder;" whose first, fifth, and sixth lines ("Ach Herr, mich armen Sünder, .. . du wolltest mir vergeben mein Sünd' und gnädig sein") correspond to the final line of "Herr Jesu Christ" ("du wollst mir Sünder gnädig sein"). In keeping with the anticipation of the Passion, however, it is distinctly possible that Bach intended more than one association, since, as we know, the passion chorale "O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden" was also sung to the same melody.

The most important musical point regarding Bach's bringing together references to three different chorales in this movement, however, is a tonal one. "Herr Jesu Christ" is in F major ending in C, as we saw; and its several phrases cadence mostly on either F or C. "Christe, du Lamm Gottes," however, begins as if in F and ends in G Dorian—that is, it is in a minor mode. And Bach presents the first two of its three phrases at two transposition levels each, corresponding to the F and C sys. The first phrase of "Ach Herr, mich armen Sunder" is Phrygian, although it sounds as though it ends on the dominant, and Bach transposes it to four different pitch levels throughout its six occurrences in the movement, the first and last two in G and C Phrygian, respectively (i.e., C minor and F minor) and the third and fourth in E and A Phrygian. The intricate details that surround Bach's building a unique tonal design from the interaction of these three chorale elements go beyond the scope of the present discussion. Suffice it to say that when the ordinarily "sharp" Phrygian mode is transposed to the level of the Ionian mode with the same final, it is necessarily flattened considerably (i.e., C Phrygian sounding like the dominant of F minor). The first, second, fifth, and sixth appearances of this phrase, therefore, introduce a very substantial flat coloring into the movement. In this and many other subtle details Bach's design is very evocative of the interaction of both tonic major/ minor and relative major/minor modes, suggesting an allegory of the interaction of the divine and the human in Jesus ("wahr'r Mensch und Gott") as well as the disparity between Jesus and the sinner whose cry of penitence underlies the chorus. The dominance of flat tonal regions in the first half of the cantata—the ending of the opening movement is heavily colored by F minor, the first recitative cadences in f, and the first aria is in c—gives way to C major in the second aria (which shifts from F to C with a corresponding shift of key signature after its first twenty measures). After that, the shift from F to C for ending of the final chorale and the intermingling of C major and C minor on its final phrase represent the believer's anticipation of death and resurrection simultaneously.

Perhaps the most striking of all such derivations of an entire cantata design from a chorale melody, however, comes not in a chorale cantata but in the cantata that is most famous for its numerological element, "Du sollt Gott, deinen Herren, lieben," BWV 77, for the thirteenth Sunday after Trinity, 1723. In that work, the subject of the next two chapters, the Law is represented in the opening movement in the various canonic devices surrounding Luther’s Ten Commandments chorale and its Mixolydian melody, while the so-called great commandment to love God and one’s neighbor constitutes the sung text of the movement and its “free” treatment of the chorale melody. The G Mixolydian melody contains an anomaly, in that it introduces the pitch Bb in its final phrase, effecting, in fact, a shift from the cantus durus to the cantus mollis that Bach extends in his opening movement to a tremendous tonal motion to C minor for the juxtaposition of God and humanity (i.e., one’s neighbor.) The net effect of this flat motion within the movement is that the return to G at the end is greatly weakened—to the point that Alfred Dürr, for example, pronounces the key of the movement as not G but C major. And the flat motion just described continues throughout the cantata, the final movements dealing with human weakness to an extraordinary degree. The final chorale, a setting of the melody “Ach Gott, vom Himmel sieh’ darein,” shifts openly to the cantus mollis—that is, to the one-flat key signature—and its ending is on the dominant, the most striking such occurrence in all Bach’s music.

Comments:

1. I have to agree with Chafe that too much has been made of the incisive, dotted rhythms representing the ‘scourging’ of Jesus in the two major Passions by Bach. Some commentators have attempted to apply this to the interpretation of BWV 127/1.

2. Chafe’s main theory is based upon determining the upward (anabasis) and downward (catabasis) movement of tonality whether spanning only a movement or an entire work (cantata, passion.)

3. Chafe gives credit to Smend where credit is due (his discovery of the untexted chorale “O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden” etc.

4. It is sad that Chafe, in a work devoted to such details in the cantatas makes the following statement: “The intricate details that surround Bach's building a unique tonal design from the interaction of these three chorale elements go beyond the scope of the present discussion.” It would certainly have been interesting indeed to see just what he had in mind, even if he only sketched out some of the possibilities that he seems to be referring to.

5. I have included the beginning of Chafe’s discussion of BWV 77 which follows directly because of his observation: “the Law is represented in the opening movement in the various canonic devices” which I believe applies to my discovery of the canons in BWV 127/1 and what they might possibly signify. |

| |

|

Christoph Wolff: Liner notes to Koopman Cantata Series |

|

[Commentary on mvt. 1 only included as notes to the Koopman cantata series, 2001]

The cantata "Herr Jesu Christ, wahr' Mensch und Gott" BWV 127 was first performed on Quinquagesima Sunday on 11 February 1725. It is based on Paul Eber's hymn of the same name, found in hymnals since 1562. The first and last verses are used unchanged. Verses 2-7 are reworked, though a few lines are kept, and clear reference is made to the gospel reading, Luke 18:31-43 (Journey up to Jerusalem, healing of a blind man). Quinquagesima being the Sunday before Lent, no music was played in church thereafter until Good Friday 1725. On that occasion the St John Passion was performed in a new version which established a connection with the chorale cantatas; for example the opening chorus was based on the chorale "O Mensch bewein", and the closing chorus on "Christe, du Lamm Gottes".

The scoring of the cantata, performed immediately before the tempus clausum the period of Lent during which no music was played in church, is unusually magnificent, calling for trumpet, two recorders, two oboes, strings and organ as well as four-part chorus and soloists. The instrumental colors in the third movement aria, with its obbligato winds, and the fourth movement recitative and aria, in which the trumpet makes a dramatic appearance, are particularly lovely. The chorale melody in the opening chorus appears in the soprano part, while the winds play another cantus firmus ("Christe, du Lamm Gottes"), and the initial phrase of the Passion chorale' Herzlich tut mich verlangen" is heard repeatedly in the continuo.

End of commentary on mvt. 1, [the rest omitted] by Christoph Wolff

Comments:

1. Wolff’s commentaries on the cantatas supplied with the Koopman series, leave much to be desired. This is a rather disappointing effort on the part of an important Bach scholar. |

| |

|

Comments and English translation by Thomas Braatz (2004, unless otherwise noted)

Contributed by Thomas Braatz (November 27-28, 2004) |

|

|