The Portrait That Does NOT Depict J. S.

Bach With Three Of His Sons Pages at The

Face Of Bach

Part 1 - Why the Portrait is Not an Accurate Depiction of Johann Sebastian Bach or Any

of His Sons

The Face Of Bach

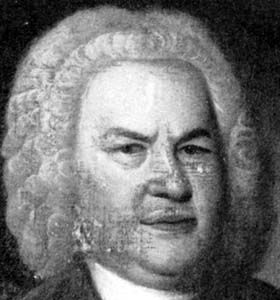

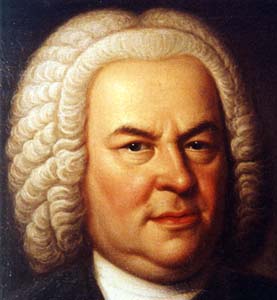

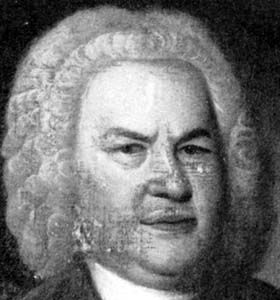

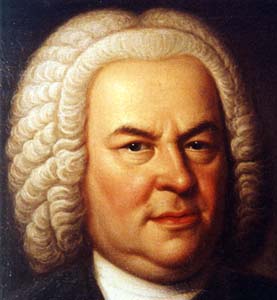

This remarkable photograph is not a computer generated

composite; the original of the Weydenhammer Portrait Fragment, all that remains of the

portrait of Johann Sebastian Bach that belonged to his pupil Johann Christian Kittel, is

resting gently on the surface of the original of the 1748 Elias Gottlob Haussmann Portrait

of Johann Sebastian Bach.

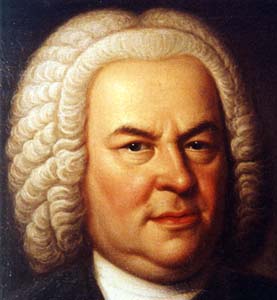

1748 Elias Gottlob Haussmann Portrait, Courtesy of William H. Scheide, Princeton, New Jersey

Weydenhammer Portrait Fragment, ca. 1733, Artist Unknown, Courtesy of the Weydenhammer

Descendants

Photograph by Teri Noel Towe

©Teri Noel Towe, 2001, All Rights Reserved

The Portrait That Does NOT Depict J. S. Bach With Three

Of His Sons

Part 1

Why the Portrait is NOT an Accurate Depiction of Johann Sebastian Bach or Any of His Sons

A Case of Mistaken Identity

Some Preliminary Conclusions About the True Identities of

the Father and Three Sons Depicted in the Group Portrait Attibuted to Balthasar Denner

Part One

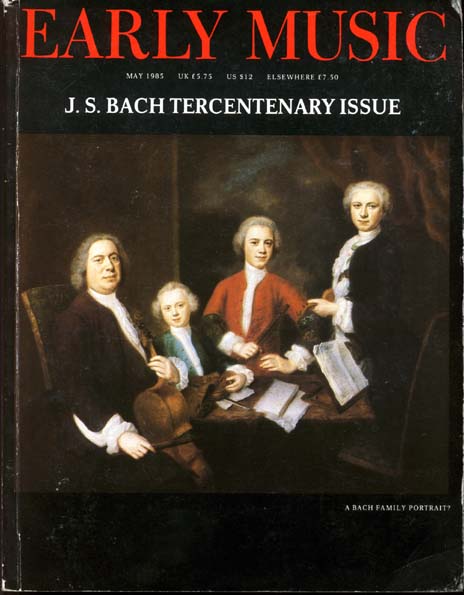

In the Spring of 1985, the Tercentenary of George Frideric

Handel, Johann Sebastian Bach, and Domingo Scarlatti, those of us who subscribed to Early

Music were flabbergasted by the cover art of the May issue:

Described as "A Bach Family Portrait", the image

circled the world in no time flat. After all, it was a world eager for new discoveries and

new additions to both the catalogue of works and our knowledge of Johann Sebastian Bach.

Our appetites had been whetted by the announcement of the discovery of the so called "Neumeister"

Chorales, which constitute not only a significant addition to the corpus of the Bach

organ works but also greatly expand our ability to evaluate and properly date his early

compositions for keyboard.

The painting, or the most important detail from it, namely

the image of the father in the family group, a man with a high forehead but what appears

to be a full head of his own hair and who holds a 'cello -- perhaps a violoncello piccolo

-- in his left hand and a bow in his right, has been widely reproduced and graces myriad

record jackets and CD booklets, especially those housing recordings of the 'cello, gamba,

and chamber music of Johann Sebastian Bach:

But does the painting actually depict Johann Sebastian Bach

and three of his sons, as Christoph Wolff and a number of other eminent Bach scholars

cautiously have surmised that it might?

For me, the instant answer in 1985 was an emphatic

"No!"

And sixteen years later, the answer remains an emphatic

"No!"

The only difference between 1985 and 2001 is, in 2001, not

only am I prepared to demonstrate why the image of the father in the Group Portrait is not

an accurate depiction of the facial features of Johann Sebastian Bach but also I am

prepared to set forth, and set forth with conviction, the case for the correct

identification of the family that is depicted in this portrait. And, before I present that

case, I cannot resist giving you a hint, because the irony of that identification is too

delicious for words: The father was a colleague and friend of Johann Sebastian Bach, and

one of the sons, most likely the middle one, the one in the red coat who is holding the

flute as though it were a field marshall's baton, was a friend and colleague of one of

Johann Sebastian's most famous sons!

The eminent art historian, Bernard Berenson, the sage of I

Tatti, observed that the first ten seconds with an object are worth the next ten years.

Sixteen years may have elapsed since that issue of Early Music arrived in my mail

box, but the memory of my initial reaction is vivid. "There is no way in the world

that the man in that painting is Johann Sebastian Bach!"

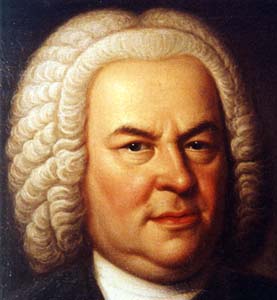

As those who have read The Queens

College Lecture here at The Face Of Bach already

know, the depiction of the father's face in any case is not an accurate depiction of the

facial features of Johann Sebastian Bach as they are acknowledged to have been, based on the known physiognomical characteristics. The careful analysis of

the facial features as they manifest themselves in the 1746 Haussmann

Portrait, the 1748 Haussmann Portrait, the skull, as well as in the Meiningen Pastel and in the Weydenhammer Portrait Fragment, which I recently have proven beyond

a reasonable doubt is what remains of the long lost portrait of Bach

that belonged to his pupil, Johann Christian Kittel, demonstrates unequivocally that

one of the most salient of those facial features was a protuberant lower jaw, a pronounced

underbite. As I point out on Page 9 of The Queens College Lecture:

"The sitter in the picture attributed to Denner (in the

middle in the examples below, with the 1748 Haussmann to its

left and the 1746 Haussmann [in its unrestored state, with all of

the overpaint removed] to its right) not only has an overbite but also does not have a

protuberant lower jaw. In addition, the teeth that support the right "third" of

the upper lip (the canine and the upper cuspid, I think they're called) project outward in

a manner that is inconsistent with what we know about Bach's dentition.

"

"

The distinctive characteristic of a pronounced underbite

was inherited by at least three of Sebastian Bach's sons -- Wilhelm Friedemann, Carl

Philipp Emanuel, and Johann Christian -- and the significance of that genetic legacy will

become clear, and not without a certain irony, later in this essay.

But I am putting the clichéed evidentiary cart several

furlongs before the scholarly horse.

Let me therefore "rein myself in", and approach

the question of the Group Portrait in something resembling a "proper" scholarly

fashion. Let me begin by setting forth succinctly what is known about the provenance of

this controversial image. Then I shall subject the facial features of the father in the

group portrait to the same series of rigorous comparison tests to which I so far have

subjected both the Weydenhammer Portrait Fragment and the Volbach Portrait. Finally, I shall set forth the case for my belief

that the group portrait attributed to Balthasar Denner depicts and depicts accurately the

facial features of one of Bach's friends and colleagues in the Capelle at the

Court of Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen.

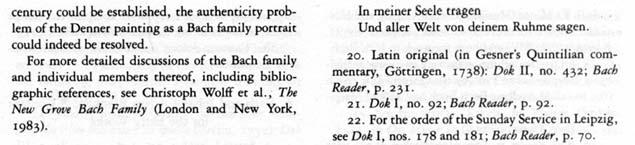

The best succinct statement of the provenance of the Group

Portrait is to be found in a lengthy footnote in Christoph Wollf's remarkable Bach -

Essays on His Life and Music, and I am confident that my good friend and colleague

will not mind if I quote from it in toto, via a pair of computer scans:

In his discussion of the Bach iconography in the recently

published 2nd Edition of the New Grove Encyclopedia of Music and Musicians, Christoph adds

the following additional, and very important bit of information:

"...a replica, in better

condition, is in a private collection in the UK..."

And the two versions, as it turns out, are quite different

in appearance!

Several months ago, while I was working on the The Queens College Lecture of March 21, 2001 - The Search for the

Portrait that Belonged to Kittel, my close friend and generous colleague, Raymond

Erickson, a renowned Bach scholar, leant me a copy of a commemorative book that he had

acquired during a visit to Erfurt in the summer of 2000. Entitled Der Junge Bach,

this valuable volume is an important anthology of articles on various aspects of the life

of Bach and the culture in which he flourished. There is also a very useful section on the

Bach portraits. I made computer scans of some of the images for study purposes, including

details from a large reproduction of the group portrait. The original photograph is too

big to be scanned easily as a single image, and I settled on the important details. At the

time, however, I did not appreciate the significance of the image that I had found in Der

Junge Bach. I did not realize that, unless it is derived from a photograph of the

"Bonham's version" (as I have now come to call the painting that surfaced in

1985, for it was at Nicholas Bonham's top class, family owned auction gallery that the

painting was sold to the collector who realized that it might just be a portrait of Bach

and three of his sons) after it had had layers of overpaint removed (which is highly

unlikely!), the image in Der Junge Bach reproduces the alternate version of the

portrait, and it is a version that differs noticeably from the Bonham's version that I

first saw on the cover of Early Music, lo these many years.

I shall return to those differences later in this essay,

but to give you some idea of the extent to which these two exemplars differ, here is the

patriarch in both versions. The familiar Bonham's version is on the left; the Der

Junge Bach version is on the right:

There are several aspects of this painting and its history

that immediately call into serious question the accuracy of its identification as a

portrait of Johann Sebastian Bach and three of his sons.

Quite apart from the anatomical objections, to which I

shall, of course, turn my attention later in this essay, I have four principal objections:

First of all, I admit that Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, when

he wrote to Johann Nicolaus Forkel about what portrait image should eventually be used as

the basis for the frontispiece of his projected biography, did not provide him with a

catalogue of all the portrait images of his father that may have existed, and I also admit

that C. P. E.'s failure to mention the existence of a family group portrait is arguably

insignificant. After all, such an image would not have lent itself to the specfic purpose

for which Forkel wanted a portrait of Johann Sebastian Bach, and for that reason alone

C.P.E. would have had no reason to mention it to Forkel, even more than he would have had

any reason to mention in such a context that he owned the 1748

Haussmann Portrait.

But, and this is an important "but", the absence

of the Group Portrait from the inventory of C.P.E.'s Estate is significant!

Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach was the de facto family

archivist. It was C.P.E. who held on to the so-called Alt Bach Archiv, the

collection of manuscripts of music composed by his ancestors that his father had

assembled, the collection that has recently been returned by the government of the Ukraine

to the Singakademie in Berlin thanks, in major part, to the stubborn and persistent

efforts of Christoph Wolff, who spent years tracking these priceless materials down. It

was C.P.E. who took especial care of that portion of his father's own legacy that came to

him when the scores and parts were divided among the surviving sons after their father's

death in 1750. In addition, one of C.P.E.'s hobbies was collecting portrait images of

famous composers and musicians.

Under such circumstances, doesn't it seem likely that C. P.

E. would have have "clawed and scratched" to obtain the group portrait that

showed him in his teens, with his father and two of his brothers, particularly if there

were two exemplars, as appears to be the case?

Personally, I think he would have gone to almost any

lengths to obtain one or the other of the two versions.

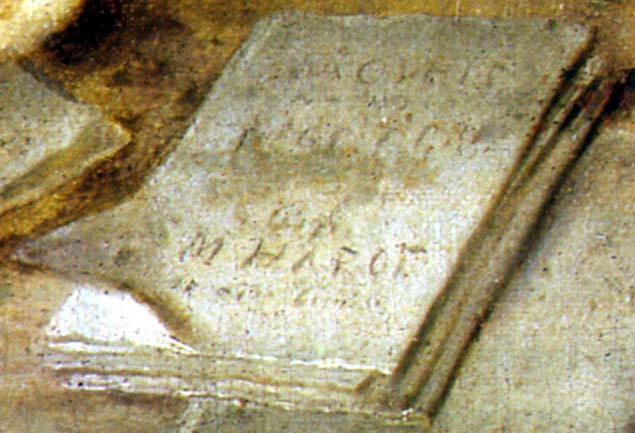

Second, there is the puzzle of the music on the table and

on the music stand. Christoph Wolff specifically mentions that the music is illegible in

the Bonham's version of the Group Portrait (In fact, Christoph wonders if it had not been

rendered unreadable deliberately.), but that is not the case with the version that is

reproduced in Der Junge Bach:

The surface of this canvass also appears to have been

seriously abraded over the centuries, but, that wear and tear notwithstanding, it still

appears as if the lettering on the sheaf of music that is visible on the table top is, and

always was, random gobbledy-gook.

Nevertheless, I knew that I had to take a stab at trying to

make out the letters. The image that popped into my mind when I started the thankless task

was sitting in the chair at the opthamalogist's.

"Read the top line, please."

"It looks like 'something', 'something', 'O', 'V',

'E', 'I', 'S'.

"Now, the second line."

"'Something' - a 'P' maybe? Then a 'G' perhaps, then a

couple of 'C's, and then a 'G' or a 'C'."

"And the bottom line?"

"'M', 'H', 'A', a 'P' or an 'F', then an 'O', and a

'T' or may be an 'F'."

What the significance or meaning of these letters is,

assuming that I am deciphering them accurately and assuming that they are meant to mean

something, eludes me, but the analysis of such things has never been one of my long suits.

To quote from Gilbert and Sullivan's The Mikado, "The task of filling up the

blanks I'll gladly leave to you."

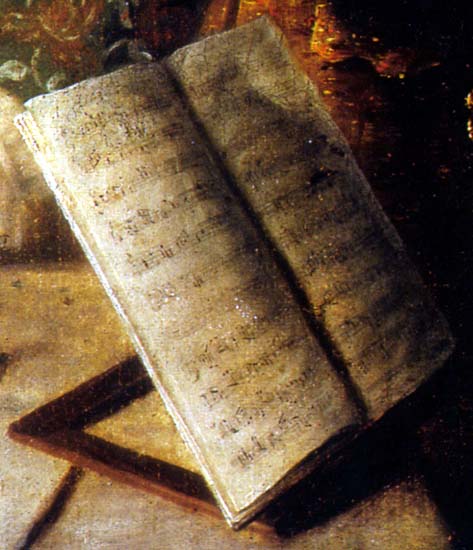

And then there is the music. Notes can be made out on the

sheets of music beneath the violin on the table, around which the youngest son has gently

wrapped his forearm

and also on the pages of the folio of music that is open on

the music stand:

Even though I once was a fairly competent singer, I make no

bones about the fact that I am not a musician. I am a music historian and an art

historian. I am not a musicologist. I therefore am not qualified to offer an opinion on

the notes that can be made out on these pages, but, somehow or other, if the notes, in

fact, are clearly discernible, transcribable, and realizable, I doubt that they will turn

out to be the handiwork of Johann Sebastian Bach. Particularly in light of the care with

which Elias Gottlob Haussmann rendered the copy of the Canon triplex à 6 vocibus

that Sebastian Bach proffers to the viewer in both the 1746 and

the 1748 versions of his famous portrait, I find it impossible to

believe that Bach would not have insisted on similar accuracy and attention to detail in

this portrait, if it is, in fact, a portrait of him and three of his sons.

My third objection is founded on the reference to the

portrait still being in the hands of family members in the late 19th century. The

annotations to the collection of photographs that so far has eluded discovery allegedly

state that there was a group portrait still in the hands of the Bach family. If that was,

in fact, the case, what branch of the family had it, and why? Please remember that, until

it was serendipitously discovered about 25 years ago that there were, in fact, descendants

of Wilhelm Friedemann Bach among us, and that the family had not, in fact, died out, as

had long been believed, the last direct descendant known of Johann Sebastian Bach was a

granddaugther of Johann Christoph Friedrich Bach who died, a spinster, in 1871. This as

yet unidentified group portrait, which may or may not have been the one that we are

presently discussing, could have been in the hands of a collateral branch of the family, I

admit -- The descendants of Bach's older brother Johann Christoph would be the most likely

ones, I guess -- but that this image has never surfaced since it was photographed in the

late 1870s borders on the inexplicable and the incredible.

And, even if it does turn out that the image reproduced in

that eagerly sought after volume is one of the two versions of the Group Portrait, that

still does not mean that it is an accurate depiction of the facial features of Johann

Sebastian Bach and three of his sones.

Fourth and finally, we must consider the implications of

the documented existence of the two versions of the painting that we are presently

considering. That there are two versions of it makes it even more incredible that C. P. E.

Bach would not have wrested one of them out of the hands of the other members of the

family in order to add to his own collection, and that is particularly so because the

group portrait is alleged to include him!

No, logic weighs in, and weighs in heavily, against the

identification of the subjects of either of the two versions of this group portrait as

Johann Sebastian Bach and three of his sons.

But those who know me well know that I am not one who will

let logic stand in the way. After all, as Lord Peter Wimsey says, the improbable possible

is always preferable to the impossible probable.

Therefore, even though logic dictates that the Group

Portrait be rejected and rejected summarily, and right now, I must see this project

through to the end, before I offer my own conclusions about the subjects of this painting.

Even though I am sure before I start that the patriarch holding the 'cello is not Johann

Sebastian Bach, I shall now put that head through the anatomical tests to which I have

already subjected the Weydenhammer Portrait Fragment , the Volbach Portrait, and the Berlin Portrait.

I know, I have already done that, but let us try it again, this time adding the head of

the Der Junge Bach version to the equation.

The same rules and criteria apply here as have applied

elsewhere at The Face Of Bach. I shall not reiterate the

specific elements of Bach's physiognomy that must be taken into consideration. For those,

I refer you to the discussion of Bach's Physiognomical

Characteristics on Page 9 of The Queens College Lecture, but,

here, for convenient reference, are the three unchallenged standards against which all

aspirants to the mantle "accurate depiction of the face of Johann Sebastian

Bach" have to be compared:

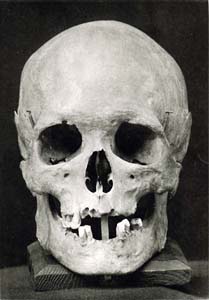

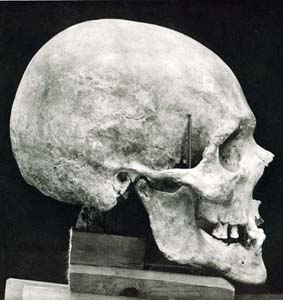

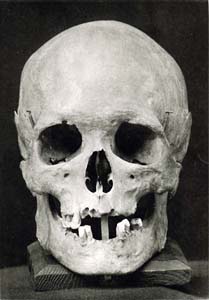

1748 Haussmann; 1746 Haussmann (overpaint removed and unrestored); Skull, as photographed

in 1895

First, a comparison of the heads in the two versions of the

Group Portrait. The familiar "1985 version", the Bonham's Version, is on the

left; the "Der Junge Bach version" is on the right:

Some subtle, but important, differences are immediately

evident. First of all, the overbite and the receding chin are even more apparent in the Der

Junge Bach version. And isn't interesting that the little bulge about a third of the

way down the nose is not in evidence in the Der Junge Bach version. The bridge of

the note is straight. Finally, the lower lip in Der Junge Bach version does not

appear to be as wide as the lower lip in the Bonham's version.

And now, let us work our way down the face, anatomical

detail by anatomical detail. Because the 1746 Haussmann Portrait

is no longer reliable, for reasons that I have made clear elsewhere, I am omitting it from

this particular discussion. The 1748 Haussmann Portrait, as I

have also explained elsewhere, is in pristine condition, and is therefore the universally

agreed upon absolute iconographical standard against which any purported portrait of

Johann Sebastian Bach must be measured.

In the comparisons that follow, the 1748

Haussmann Portrait is in the middle, with the Bonham's version of the Group Portrait

either above it or to its left, and with the Der Junge Bach version either below

it or to its right, as circumstances dictate. I apologize that I do not have at the moment

crisper scans of the Bonham version, but I shall replace them as soon as I am able to

obtain a basic image of crisper and higher resolution.

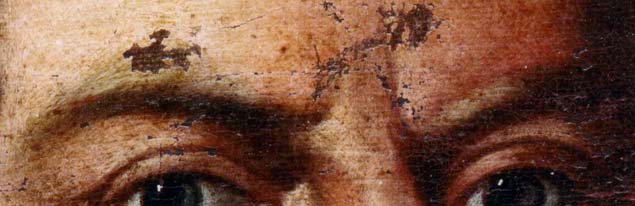

First the brow:

The eyebrows do not have the same distinctive angles to

them that are so much in evidence in the 1748 Haussmann Portrait,

and there is no hint of the distinctive vertical furrows where the eyebrows meet the

bridge of the nose. The beginnings of these distinctive anatomical features can, however,

be seen in the Weydenhammer Portrait Fragment, which dates from

the same time period to which the Group Portrait is assigned:

Next the eyes:

While the eye color does seem to be the requisite blue

grey, it is at once apparent that the eyes of the patriarch in the Group Portrait are not

those of the Johann Sebastian Bach of the 1748 Haussmann Portrait.

First of all, the distinctive difference in the shape and contour of the bridge end of the

right eye and bridge end of the left eye is not to be seen, and the distinctive curve of

the bridge end of the lower lid of Bach's right eye is not in evidence. Finally, as my

long time friend and colleague Seth B. Winner pointed out to Bill Scheide and me, Bach was

slightly "wall eyed" in the right eye. This is a subtle anomaly, to be sure, but

the patriarch of the Group Portrait is not wall-eyed. Finally, the eyelids show no hint of

incipient ptosis or blepharochalasis, which as I have shown elsedwhere,

was a hereditary condition in the Bach family. Once again, I will call on the Weydenhammer Portrait Fragment for "back-up":

The distinctive curve of the lower lid of the right eye is

in evidence; the difference in eye shape is also clearly apparent; the first hints of the ptosis

and the blepharochalasis in the right eye are clearly discernible, and,

finally, the right eye is slightly "wall eyed".

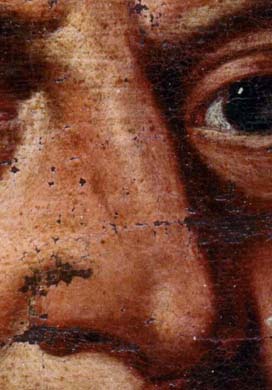

The bags under Bach's eyes are also quite distinctive, so

let's have a look at those:

The crease that marks the "bottom" of the bags

under Bach's right eye begins at the bridge end of the eye itself. The crease that marks

the bottom of the bags under the Group Portrait patriarch's right eye does not, at least

in the Bonham's version. With the Der Junge Bach version, it is not easy to tell,

but it does not appear to begin at the bridge end of the eye itself.

Let us look yet again at the Weydenhammer

Portrait Fragment.

Please note that the crease that marks the

"bottom" of the bags under Bach's right eye begins at the bridge end of the eye

itself, just as it does in the 1748 Haussmann Portrait.

Next, the nose:

I remarked earlier that the Der Junge Bach version

does not have the distinctive Bach bulge in the bridge of the nose about one-third of the

way down the bridge, but the Bonham's version does. Nonetheless, neither form of the nose

seems to match the nose in the 1748 Haussmann Portrait.

The nose of the Weydenhammer Portrait

Fragment reinforces these observations. The flare in the bridge of the nose, and the

shape of the nostrils are the younger version of the nose in the 1748

Haussmann Portrait; in this triptych of examples, the Weydenhammer

Portrait Fragment and the Bonham's Version of the Group Portrait are to the left and

right of the 1748 Haussmann Portrait, respectively:

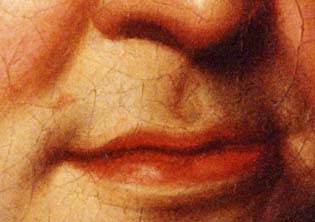

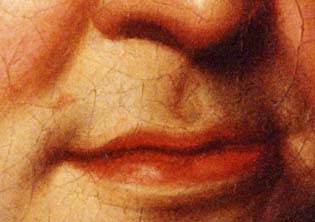

Now, the most telling anatomical detail of all, the mouth:

As before, the 1748 Haussmann Portrait

is in the middle. That the patriarch in the Group Portrait has an overbite is undeniable,

as undeniable as it is that Bach had a pronounced underbite. And there is absolutely no

dispute about Bach having had an underbite. The evidence provided by the photos of the skull confirms it. For convenience, here are the profile and

frontal photos of the skull, with the 1748

Haussmann Portrait in the middle:

At the risk of trying your patience, I turn once again to

the Weydenhammer Portrait Fragment for additional support. Once again, in this triptych of

examples, the Weydenhammer Portrait Fragment and the Bonham's

Version of the Group Portrait are to the left and right of the 1748

Haussmann Portrait, respectively:

In the Weydenhammer Portrait Fragment,

one finds the same underbite that one finds in the 1748 Haussmann

Portrait, albeit with more teeth.

Finally, the jaw:

Both the patriarch of the Group Portrait and Bach are heavy

men. In fact, the chubbiness of their faces shows that they were each corpulent to the

same prodigious degree. Please note that neither man has a neck; the jowls dissolve into

the collar of the shirt without the intervention of a distinct neck. Please also note that

there is significantly less shadow under the chin of the partiarch of the Group Portrait

that there is under the chin of the Bach of the 1748 Haussmann

Portrait.

One more time, the evidence of the 1748

Haussmann Portrait is supported by the evidence of the Weydenhammer

Portrait Fragment, which I remind you dates from the same period in Bach's life from

which the Group Portrait has been hypothesized to date:

Once again, the shadows say it all. It does not matter that

the Bach of the Weydenhammer Portrait Fragment is 25 to 30 pounds

lighter than the Bach of the 1748 Haussmann Portrait, the

prominent chin beneath the undershot lower row of teeth creates a shadow that is totally

absent from both of the exemplars of the Group Portrait.

In sum, the face of the patriarch in the Group Portrait, no

matter which of the two exemplars you choose to use for the comparison, fails every single

one of the anatomical tests that must be met in order to be accepted as an accurate

depiction of the facial features of Johann Sebastian Bach.

Therefore, if the face of the patriarch in the Group

Portrait is not the face of Johann Sebastian Bach, the faces of the three sons cannot be

the faces of any of the sons of Johann Sebastian Bach.

Nonetheless, pictures, as I have remarked elsewhere, tell

different stories to different people. In his commentary on the Group Portrait, which I

reproduce in toto near the top of this page, Christoph Wolff writes of,

"...the striking similarity between a pastel portrait of C. P. E. Bach from ca. 1733

and the violinist on the right hand side of the Denner painting..." that he sees.

Needless to say, I do not agree, and, in fairness to him, my valued friend and thoughtful,

generous colleague, I must explain why.

First, to make matters easier, and, at the risk of being

accused of political incorrectness in yet another venue, I shall invoke the spectre of

Sidney Toler and that movie detective of yore, Charlie Chan, and henceforth shall refer to

"the violinist on the right hand side" as the Number One Son, the confident

flutist in the center of the painting as the Number Two Son, and the boy standing next to

the patriarch as the Number Three Son.

Here are the Bonham's Version of the Number One Son on the

left and the Der Junge Bach Version of the Number One Son on the right, with the

1733 pastel of C. P. E. Bach in the middle:

Now, here are the portrait heads, in the same order:

Please note that the Number One Son has an overbite in both

versions of the painting; it is especially obvious in the Der Junge Bach version

of the picture. That Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach had an underbite like his father is also

discernible from a careful examination of the pastel portrait done by his then teenaged

distant cousin, Gottlob Friedrich Bach, the artist who created the Meiningen Pastel

portrait of Johann Sebastian Bach. That C. P. E. had an underbite, however, can be

confirmed easily from other unquestioned portraits from life. Here are two of them, both

of which can be dated precisely. On the left, C. P. E.'s head from one of the pastel

portraits that Johann Philipp Bach, the son of the creator of the Meiningen Pastel, made

of his godfather in 1773; on the right, C. P. E. 's head from the group portrait

watercolor by Stöttrup, which is dated 1784.

There is no less doubt that C. P. E. Bach had an underbite

than there is doubt that Number One Son had an overbite.

Alas, the Number One Son cannot be Carl Philipp Emanuel

Bach in his late teens.

I now refine my earlier statement:

Therefore, if the face of the patriarch in the Group

Portrait is not the face of Johann Sebastian Bach, and, if the face of the violinist

standing at the right in the painting is not the face of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, the

Group Portrait that some attribute to Balthasar Denner can not be a depiction of Johann

Sebastian Bach and three of his sons.

That's the bad news.

Please click on  for the good news! {:-{)}

for the good news! {:-{)}

Please click on  to return to the Index Page at The Face Of Bach.

to return to the Index Page at The Face Of Bach.

Please click on  to visit the

Johann Sebastian Bach Index Page at Teri Noel Towe's Homepages.

to visit the

Johann Sebastian Bach Index Page at Teri Noel Towe's Homepages.

Please click on the  to visit the

Teri Noel Towe Welcome Page.

to visit the

Teri Noel Towe Welcome Page.

TheFaceOfBach@aol.com

Copyright, Teri Noel Towe, 2000, 2001, 2002

Unless otherwise credited, all images of the Weydenhammer Portrait: Copyright, The

Weydenhammer Descendants, 2000

All Rights Reserved

The Face Of Bach is a PPP Free Early Music

website.

The Face Of Bach has received the HIP Woolly Mammoth Stamp of Approval from The HIP-ocrisy Home Page.