The The Search for the Portrait that Belonged to Kittel Pages

at The Face Of Bach

The Queens College Lecture of March 21, 2001 - Page 9 - Bach's Physiognomical

Characteristics

The Face Of Bach

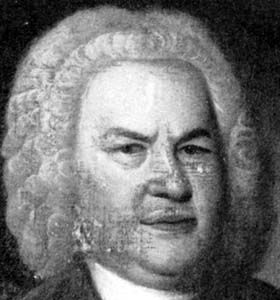

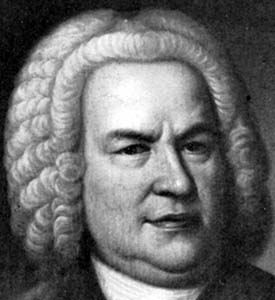

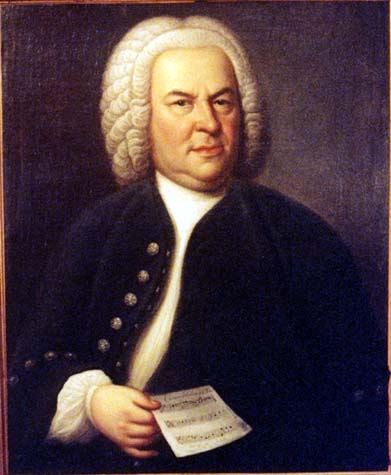

This remarkable photograph is not a computer generated

composite; the original of the Weydenhammer Portrait Fragment, all that remains of the

portrait of Johann Sebastian Bach that belonged to his pupil Johann Christian Kittel, is

resting gently on the surface of the original of the 1748 Elias Gottlob Haussmann Portrait

of Johann Sebastian Bach.

1748 Elias Gottlob Haussmann Portrait, Courtesy of William H. Scheide, Princeton, New Jersey

Weydenhammer Portrait Fragment, ca. 1733, Artist Unknown, Courtesy of the Weydenhammer

Descendants

Photograph by Teri Noel Towe

©Teri Noel Towe, 2001, All Rights Reserved

The Search for the Portrait that Belonged to Kittel

The Queens College Lecture of March 21, 2001

Bach's Physiognomical Characteristics

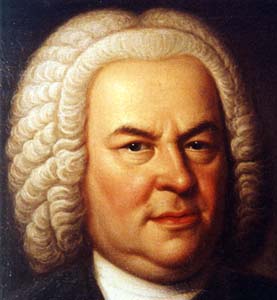

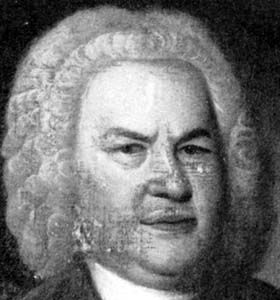

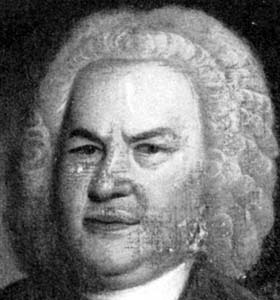

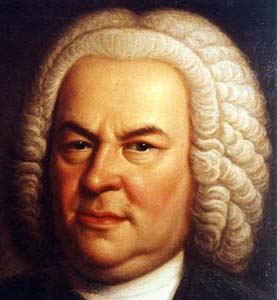

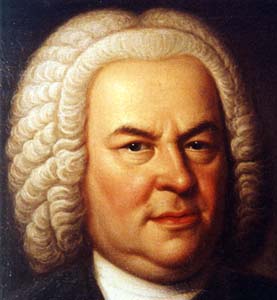

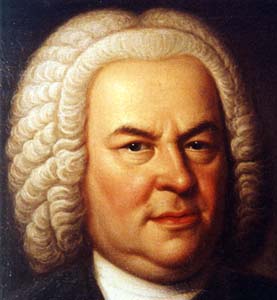

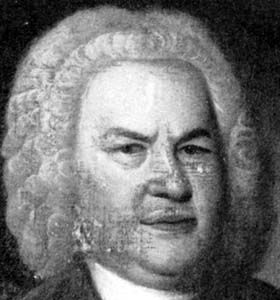

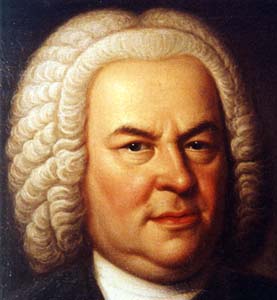

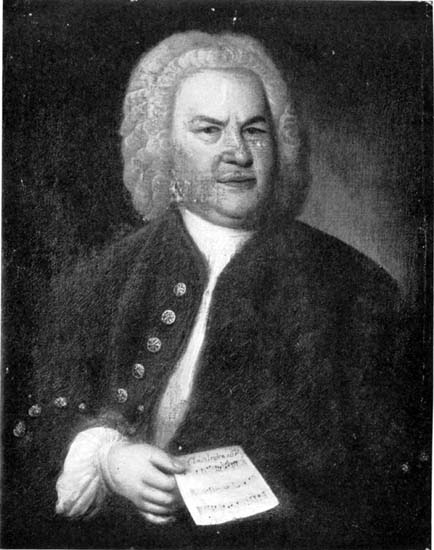

And, now before we catalog the specific physiognomical characteristics

that make Bach's face Bach's face, here, for reference during that process, are the three

standards, by themselves:

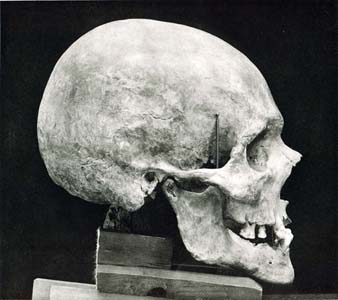

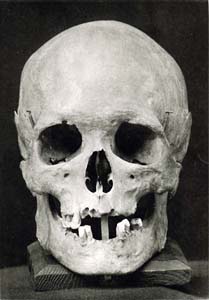

1748 Haussmann; 1746 Haussmann (overpaint removed and unrestored); Skull, as photographed

in 1895

Perhaps the best succinct explanation of the physiognomical factors that

traditionally have had to be considered in the authentication process for a portrait

alleged to be one of Johann Sebastian Bach is Gerhard Herz's summary in his Musical

Quarterly review of Besseler's Fünf Echte Bildnisse:

"In the absence of historical documents and authenticated

signatures, Besseler attempts his identification from anatomical and physiological traits.

He reasons that in addition to such well known characteristics as Bach's protruding lower

jaw or his double chin at least one other such sufficiently unusual peculiarity that

distinguishes the composer's physiognomy ought to be found. In his search Besseler

found..., along with the common predominantly blue color of the eyes, an unusual asymmetry

of the eyes the nature of which he documents ably with the help of a scientifically usable

copy of Bach's skull.

"Crucial to the author's whole theory is the recognition of

a certain abnormal condition of Bach's upper eyelids,... Bach had what the specialist

terms blepharochalasis, a not infrequent, often hereditary, slackening of the

skin of the upper lid. It causes the usually taut and raised lid to form a thick fold and

to droop -- in extreme cases, all the way down to the eyelashes. The authenticated Haussmann Portraits ... and the small pastel, owned

by Paul Bach [the Meiningen Pastel]... show clearly this anomaly, which is considerably

more pronounced in the right lid." (Herz, MQ, p. 117)

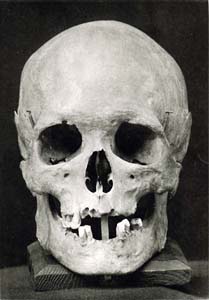

In this context, Charles Sanford Terry's description of Bach's remains

is worth repeating:

"... the almost perfect skeleton of an elderly male,

well-proportioned, not large of stature, with massive skull,

receding forehead, shallow eye-sockets, and heavy jaws." (Charles Sanford Terry,

"Bach, A Biography", Oxford, 2nd Ed., 1932, p. 279)

So what are the criteria that traditionally have been considered

essential to an accurate depiction of Bach's face? Working from the top down, so to speak,

they are

- A massive skull,

- A receding forehead,

- drooping eyelids, particularly over the right eye,

- shallow eye-sockets,

- unusual asymmetry of the eyes,

- predominantly blue color of the eyes, and

- protruding jaw and double chin

To this list, I would add another four, some of which, arguably, are

refinements of traditional ones:

- a distinctive and asymmetrical furrowed brow that gives Bach an aura that

is at once severe and mischievous,

- the long nose with what appears to be a slight arch about a third of the

way down the bridge. (This part of the nose is one of the anatomical details for which the

1746 Haussmann painting is particularly unreliable.)

- the distinctive shape of the mouth, the lower lip, and the crease at the

right side of the mouth. This aspect of Bach's face is particularly distinct in the 1748 Haussmann.

- the distinctive outline of the cheekbone and the jaw on the left side of

the face, an outline that can be perceived clearly in the boundaries between light and

shadow on the face.

There is one additional, very subtle facial peculiarity apparent in the 1748 Haussmann portrait, but I shall defer the discussion of that

for the present, if I may.

For me, the shape and the configuration of the jaw are especially

important, and I am puzzled that greater emphasis has not been given to this aspect of

Bach's physiognomy in any of the examinations of the alleged Bach portraits that I have

studied so far.

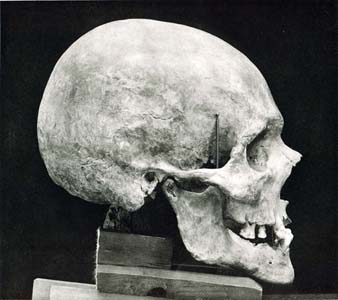

That Bach's lower jaw extended beyond his upper one is readily apparent

to anyone who examines either one of the Haussmann portraits

with any care. The skull confirms that Bach had an underbite and

that it was significant. Still, those who deal with the daunting problems of the Bach

iconography seem reticent, almost embarrassed, to address the stark reality that Bach was

born and went through life with an unpleasant and conceivably uncomfortable physiognomical

trait, one now correctible by orthodonture and, in extreme cases, by surgery, and,

furthermore, a trait that is perceived by the overwhelming majority, in Western cultures

at least, as "unattractive". Consider the discussion of what are discreetly

described as "Abnormal Jaw Relationships" in the 1985 Edition of The

Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons Complete Home Medical Guide (hereafter

cited as "CHMG '85")

"Disproportion or malposition of the jaws rarely affects

chewing ability, but often causes concern for esthetic reasons. Treatment can vary from

simple orthodontics to extensive bone surgery, depending on the severity of the problem.

Surgical treatment of severe abnormalities (orthognathic surgery) is becoming more

commonplace." (CHMG '85, p. 693)

An example of the down-playing of Bach's protuberant lower jaw is the

sculpture that Carl Seffner was commissioned to create and build on a cast of the skull, using the skin thicknesses, etc., that Dr. His's studies and

those of his colleagues had indicated to be the statistical norms.

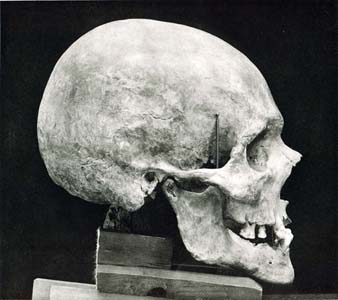

Here is a photo of the profile of one of the Carl Seffner busts, taken

from the 1895 Exhumation Report, beside a photo of the profile of the skull,

taken from the same source.

One sees immediately that the protuberant lower jaw is not

accurately reflected in the Seffner sculpture. That this so is confirmed by a subsequent

photograph in the His Report.

The portrait bust is cut away so that the viewer can see how the

"flesh" was applied to a cast of the skull, based on His's paradigms. The effect

of the underbite is clearly downplayed.

The mitigation of the protuberant lower jaw seems to be ubiquitous.

Consider the profile commemorative medallion by Zeissig that was struck on the occasion of

the 250th birth anniversary Bach Fest in Leipzig in 1935:

The extent of the protuberant lower jaw has been minimized

yet again.

Anyone who still has any doubt that Bach had a protuberant

lower jaw need only look at "flopped" versions of the Haussmann portraits to be

convinced. The old adage is that familiarity breeds contempt, and we are all

so familiar with the Haussmann portraits that it is well nigh impossible for us to look at

them with the fresh perspective that "flopping" the images provides:

Paying particularly close attention to the shape and size of the lower

jaw in the various portraits and, especially to the underbite, which is a crucial

criterion, yields some fascinating results. For example, to my knowledge -- and I

emphasize that I am by no means sure that I have seen all of the literature on the

painting -- none of those who has sought either to authenticate or to discredit the Group Portrait, allegedly of Sebastian Bach and three of his sons,

that turned up in 1985, that has been ascribed to Balthasar Denner, and that has been

dated in the early 1730s, seems to have spent much time comparing the mouth and jaw of the

"Bach" of that portrait with either of the Haussmann

portraits. Had any of them done so, the Group Portrait would

have been dismissed at once, despite certain other arguable similarities, as not

portraying accurately the facial features of Johann Sebastian Bach. The sitter in the Group Portrait (in the middle in the examples below, with the 1748 Haussmann to its left and the 1746

Haussmann to its right) not only has an overbite but also does not have a protuberant

lower jaw. In addition, the teeth that support the right "third" of the upper

lip (the canine and the upper cuspid, I think they're called) project outward in a manner

that is inconsistent with what we know about Bach's dentition.

On the other hand, the Meiningen

Pastel passes the protuberant lower jaw test with flying colors, and both the slight

arch in the nose and the distinctive furrowed brow are there, too. A careful examination

of the Meiningen Pastel, which, I remind you, is the only

portrait of Bach that has a shot at a complete and unbroken provenance, also strongly

suggests that Bach had more teeth, both upper and lower, than he did at the time that the

Haussmann portraits were painted.

.

.

There is, of course, a subsidiary issue that affects the

comparison of the appearance of Bach's mouth, and that is the number of teeth that were

actually still in his jaws at the time that a given portrait was painted. Bach's skull is missing quite a few teeth, and, although one must

allow for the probability, if not the certainty, that teeth may have been lost (The

skeleton is incomplete, to begin with, and the condition of the upper jaw suggests that

the upper lateral and central right teeth, and perhaps the upper left lateral were

dislodged and lost either during the 144 years of interment or during the exhumation

process.), the configuration of the mouth in both the Meiningen

Pastel and the 1748 Haussmann Portrait confirms that there

were teeth missing. The need to allow for and compensate for the uncertainties of the

state of Bach's dentition at various times of his life complicates any authentication

process, since, at least until the appearance of the Weydenhammer

Portrait Fragment, all of our authentic standards for comparison date from the end of

his life.

It was an allowance that Carl Seffner clearly did not make

when he built his famous sculpture, as both the profile photograph, and the cutaway

photograph attest:

Both the upper and the lower jaw of the bust provide firm

support for the muscle and skin on top of them, and they do so in a way that implies the

presence in the jaws of many more teeth than Bach actually had in his jaws in the last

years of his life.

One further point needs to be made about the dental

evidence that the skull provides. Particularly when you allow for

the probable posthumous loss of the two teeth in the righthand portion of the center of

the upper jaw and one on the upper lefthand portion, it is clear that, despite extensive

tooth loss, there was still what is called intermaxillary support. The remaining teeth in

the lower jaw were still able to support the remaining teeth in the upper jaw, which

prevents that total collapse of the structure of the lower face that is a hallmark of a

totally toothless face.

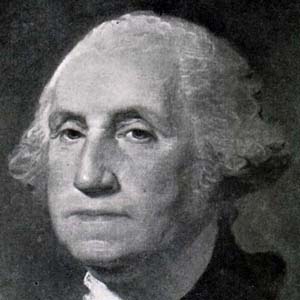

That the presence or absence of teeth in the jaws can have

a powerful effect on the contours and fullness of a person's face we already know. Once

again, I turn to George Washington as the paradigm example.

Here, lined up in a row are the heads of the Virgina

Regiment Portrait of 1772, the Ramage Miniature of 1789, and the Athenaeum Portrait of

1796:

The effect of some teeth, no teeth, and ill-fitting false

teeth is apparent.

In addition, there is a similar and equally instructive

comparison within the Bach family icongraphy. Please consider these two images of Carl

Philipp Emanuel Bach, both of which can be dated precisely. On the left, CPE's head from

one of the pastel portraits that Johann Philipp Bach, the son of the creator of the Meiningen Pastel, made of his godfather in 1773; on the right,

CPE's head from the group portrait watercolor by Stöttrup, which is dated 1784.

The distinct differences that can be seen, in the left side

of C. P. E.'s mouth particularly, indicate the loss of a significant number of teeth over

the course of a decade.

If such a loss of teeth can be documented for the son, we

are unwise to ignore the implications of tooth loss when dealing with the father.

And, ultimately, anyone interested in Johann Sebastian

Bach's face and what it actually looked like has to address an emotional issue, if you

will, of gargantuan proportions. Considering the acknowledged societal aesthetic antipathy

to "malocclusion", is it possible that the reason that there are -- and were --

so few documented images of Sebastian Bach is his own disquiet with his own face,

something that he could not change? If that were, in fact, to prove to be the case (and it

is, alas, a hypothesis unlikely ever to be proven or disproven), it certainly would

explain why he is not known ever to have taken the initiative to prepare and market a

protrait print of himself or to have acquiesced to any suggestion that a popular portrait

print be prepared and marketed. Considering his renown, such a portrait print certainly

would have sold, and, since he was in the business of selling his own musical publications

and those of his colleagues, he easily could have sold a portrait print of himself, too.

The blunt fact remains that, for whatever reason, he

didn't.

Now let us consider the furrowed brow and the notorious

drooping eyelids.

These distinctive features can be judged initially only on

the basis of the two Haussmann portraits, for the skull is of

help only in confirming the asymmetry of the eyes. About the distinctive furrowed brow,

little more need be said. It is present in the two Haussmann

portraits. There is one subtle aspect of the brow, however, that has disappeared from

the surface of the 1746 Haussmann portrait, a distinctive element

that is clearly visible in the the 1748 Haussmann Portrait and

that also can be seen in the direct copies of the 1746 Haussmann

that predate the restorations that began in 1852. Please note that, by 1746, an

additional, tiny vertical ridge or wrinkle on the right brow that has no corollary on the

left has begun to develop. To show this quirk, I here juxtapose the 1748

Haussmann with the Friedrich and the J. N. David copies of the 1746

Haussmann. It is worth noting that, if the Friedrich and David copies are reliable,

this additional wrinkle had become significantly more pronounced by the time that Bach sat

for Haussmann in 1748. In fact, this subtle detail is one of the

many factors that support my contention that the 1748 Haussmann

is the product of a second, distinct series of sittings and not a replica of the 1746 Haussmann.

The nature and the significance of the drooping eyelids

demand a closer examination, however. In his "long and detailed appendix" (Herz,

MQ, p. 177) to Besseler's book, Dr. Ernst Engelking, a distinguished ophthalmologist at

the University of Heidelberg, sets forth the case for the condition being blepharochalasis,

but that is not the only such condition with which Bach could have been afflicted.

Before doing even a bit of preliminary research on this

important point, I fortuitously had the opportunity to take the matter up in social

conversation with an old friend, a now retired medical doctor who was for many years an

internist. Rudd Procario observed that, while Dr. Engelking's diagnosis of blepharochalasis

was not by any means "wrong", particularly since it can be seen in the portrait

of Bach's father, Johann Ambrosius, and of at least three of his sons, it should not be

forgotten that blepharochalasis is but one type of "drooping eye lid",

and he suggested that I familiarize myself with the "umbrella" condition, which

he told me is called ptosis.

Later, I turned once more to The Columbia University

College of Physicians and Surgeons Complete Home Medical Guide:

"Drooping Upper Lids

[First paragraph about childhood conditions

omitted]

In adults, drooping eyelids -- the medical term is

"ptosis" -- is a sign of muscle weakness in the eyelid. Sometimes the weakness

is the effect of old age. Ptosis may also result from nerve or muscle damage due to an

injury or a disease such as diabetes, myesthenia gravis, stroke, or aneurysm inside the

skull...." (CHMG, '85)

In reading that brief description of the possible causes of

a drooping eyelid, the word that jumped out at me was "diabetes". Literally

moments before, I had been reading Christoph Wolff's thoughtful and carefully researched

speculations about Bach's medical problems in his later years:

"No reliable medical diagnosis can be made in

retrospect on the basis of [the] scanty information, but the most convincing hypothesis

suggests an old-age-related diabetic condition as the origin of Bach's final illness.

Untreated diabetes may result in neuropathy, encephalosis, eye pains, vision problems,

inflammation of the optic nerves, glaucoma, cataracts, or blindness. Intermittent

hypoglycemia, which characteristically leads to an alternating intensifying and subsiding

of the various symptoms, would account for temporary improvements reported in Bach's

deteriorating eyesight and the observable changes in his handwriting." (Wolff, JSBTLM, 2000, p. 443)

As we have seen, another sign of the condition can be ptosis,

drooping eyelids. This consideration is important, because it indicates that the condition

can wax and wane, relatively quickly, and I suspect that this would also be the case even

if the condition was pre-existing because of the hereditary predisposition to blepharochalasis,

which Bach certainly had. It is also significant that the portraits of Sebastian Bach and

his immediate family show irrefutably that the progress of the condition, whether ptosis

or blepharochalasis or both, differed from family member to family member.

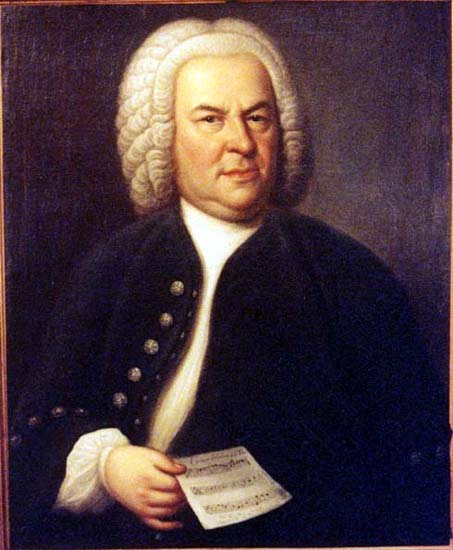

Here are "close-ups" of three generations of the

family, all in a row. First, Johann Ambrosius, Sebastian's father, in an undated painting,

that I would estimate shows him at the age of 40 to 45, therefore between 1685 and 1690.

Next is Sebastian, from the 1748 Haussmann portrait. And then

comes one of the two justly renowned Thomas Gainsborough portraits of John Christian Bach,

which were painted in 1776, when he was 40 going on 41.

It is immediately apparent that all show signs of the

condition, and, therefore, that it is clearly hereditary in the family, thus confirming

Dr. Engelking's diagnosis of blepharochalasis, but, whether the differing rate of

progression is attributable just to the blepharochalasis or is a combination of ptosis

and blepaharochalasis, the fact that John Christian's drooping eyelids are

perhaps more advanced at 40 than his father's at 61 to 63 but that Johann Ambrosius's are

considerably less advanced at 40 to 45should make the message clear to all and sundry:

The drooping right eyelid does NOT necessarily have to be

advanced to the degree that it is in the Haussmann portraits in

order for the face depicted in an alleged portrait of Johann Sebastian Bach to be an

accurate or genuine portrait of Johann Sebastian Bach.

But there is yet another aspect of the Bach family's

drooping eyelids that needs to be addressed. Sebastian Bach's drooping eyelids have a

bloated, puffy quality that neither his father's nor his son's have. What does this mean?

When one considers as well the ruddy cheeks, a sign of high blood pressure in many men,

the puffiness of the eyelids suggests that, in addition to the complaints that Christoph

Wolff enumerates, Bach suffered from high blood pressure and that he had a water retention

problem, too. The impact of such conditions has to be taken into account when assessing

the fundamental elements of Bach's physiognomy.

Obviously, more detailed research needs to be done on the ptosis

and blepharochalasis that was widespread in the Bach family. Even the distant

cousin Johann Ludwig Bach, the father of the creator of the Meiningen Pastel, had it, and,

significantly, his is considerably more advanced over the right eye than it is over the

left!

Now, is there anything else that the two Haussmann

portraits can tell us about the physiognomical characteristicsof Johann Sebastian Bach?

The Haussmann Portraits, to put it bluntly, depict a man

who is obese. As Rudd Procario said to me, "Teri, that man was fat!" Independent

analogous confirmation of Bach's corpulence can be found in a depiction of Carl Philipp

Emanuel Bach and in a portrait of Handel. First, let us have another look at the Stöttrup

watercolor, because it contains a full length portrait of C. P. E., who at the age of 70,

appears to be almost as heavy, if not as heavy, as his father was in his early 60s.

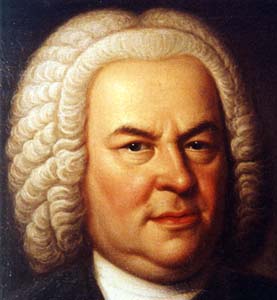

A direct comparision of the 1748

Haussmann Portrait with the famous portrait of Bach's exact contemporary George

Frideric Handel that Thomas Hudson painted in that same year, 1748, is also instructive,

especially since Handel's gourmandise and prodigious girth are amply documented in the

literature, anecdotal and otherwise.

Assuming that they were approximately the same height, they

could have worn each other's clothes!

And now, finally, let us "cut to the bone", as

George Smiley says to Connie Sachs in the television dramatization of John LeCarré's Smiley's

People, and begin our examination of the Weydenhammer Portrait

Fragment, a previously unknown depiction of Johann Sebastian Bach.

Please click on  to advance to Page 10.

to advance to Page 10.

Please click on  to return to the Index Page at The Face Of Bach.

to return to the Index Page at The Face Of Bach.

Please click on  to visit the

Johann Sebastian Bach Index Page at Teri Noel Towe's Homepages.

to visit the

Johann Sebastian Bach Index Page at Teri Noel Towe's Homepages.

Please click on the  to visit the

Teri Noel Towe Welcome Page.

to visit the

Teri Noel Towe Welcome Page.

TheFaceOfBach@aol.com

Copyright, Teri Noel Towe, 2000 , 2002

Unless otherwise credited, all images of the Weydenhammer Portrait: Copyright, The

Weydenhammer Descendants, 2000

All Rights Reserved

The Face Of Bach is a PPP Free Early Music

website.

The Face Of Bach has received the HIP Woolly Mammoth Stamp of Approval from The HIP-ocrisy Home Page.