The Search for the Portrait that Belonged to Kittel Pages at The Face Of Bach

The Queens College Lecture of March 21, 2001 - Page 4 - Codifying my Modus Operandi - Part 1

The Face Of Bach

This remarkable photograph is not a computer generated composite; the original of the Weydenhammer Portrait Fragment, all that

remains of the portrait of Johann Sebastian Bach that belonged to his pupil Johann Christian Kittel, is resting gently on the surface

of the original of the 1748 Elias Gottlob Haussmann Portrait of Johann Sebastian Bach.

1748 Elias Gottlob Haussmann Portrait, Courtesy of William H. Scheide, Princeton, New Jersey

Weydenhammer Portrait Fragment, ca. 1733, Artist Unknown, Courtesy of the Weydenhammer Descendants

Photograph by Teri Noel Towe

©Teri Noel Towe, 2001, All Rights Reserved

The Search for the Portrait that Belonged to Kittel

The Queens College Lecture of March 21, 2001

Codifying my Modus Operandi - Part 1

Let me quickly give you some examples.

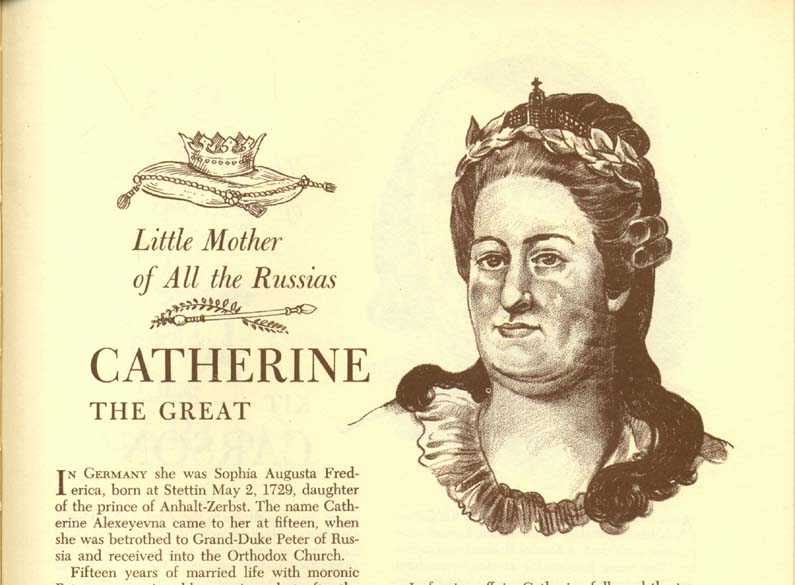

First, let me introduce you to Princess Sophia Augusta Frederica of Anhalt- Zerbst. On the left, she is 11. On the right, she is about

14:

and now let me present to you Ekaterina Alexeievna, Grand Duchess of All the Russias. On the left, in a portrait by Grooth, she is

in her middle 20s; on the right, in a portrait by Rotari, she is 31.

Of course, Sophia and Ekaterina went on to become the Russian Empress popularly known as Catherine the Great. Perhaps the

best known portrait of Catherine is the bust portrait by Shibanov that shows her at 57:

The monumental painting on the left, by Roslin, was painted during the twilight of her 34 year reign, and it is "Official Portraiture", if

ever there was. (I just adore the way she is wielding that sceptre!) The portrait on the right, by Borovikovsky, was painted in the last

months of Catherine's life, and is the very antithesis of the Roslin, a lusciously private portrait, a well-to-do old lady at ease in the

gardens of her favorite country house.

All seven of these portraits have impeccable provenance, but, at least at first glance, one would be, at a minimum, hesitant to say

that the subject of all seven was the same woman. Yet all seven of these images -- and quite a few others -- have to be analysed,

evaluated, collated, and accounted for in the compilation of the list of physical attributes that one would assemble for an image

authentication dossier for Catherine. After all, the contenders might not prove as easy to evaluate as this one

or this one!

I don't know what you think, but, in that one, I think that she looks like Rosalind Russell! (A college student acquaintance of mine,

however, contends that she looks like Elizabeth Taylor.)

Now, another Queen of distinction:

On the left is the portrait of the 13 year old Elizabeth Tudor that was painted for her father, Henry VIII, in 1546. On the right is the

legendary "Armada Portrait", now at Woburn Abbey, which depicts Elizabeth Tudor at 55, going on 56. Very quickly one sees the

similarities, most notable among them, the distinctive, elegant curve of Elizabeth's nose.

But now we have to contend with an ugly reality in the world of portraiture, the "real world", iconographical "wild card" that I call

the Stridex™ Factor. (For those of you who are unfamiliar with the name, Stridex™ was the most widely used "over the counter"

acne reduction medication when I was a teenager; it was good, but it was nowhere near as effective as the air brushes that were

standard equipment for the photography studios which contracted to take the portraits for the year book!) Elizabeth Tudor was vain

and very sensitive about her looks. In 1598, for example, she dressed down the Archbishop of Canterbury for having the audacity,

in a sermon, to say that "time had sowed meal in her hair". As an older woman, she wore the most obvious red wigs, a feature

clearly to be seen in the Armada Portrait.

Elizabeth also was in a position to exercise firm and decisive control over the substance of official portraits, and she did not hesitate

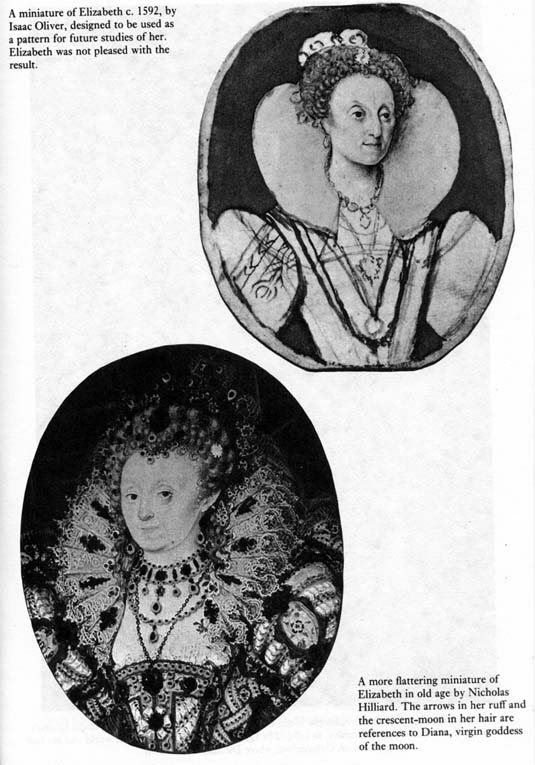

to do so. Here are two miniatures, painted during the last ten to fifteen years of her life.

The upper image, a miniature by Isaac Oliver that was intended to provide a standard image for medallions, was rejected by the

Queen. The lower image, a portrait by the eminent miniaturist Nicholas Hilliard, apparently did meet with her approval. But, for our

purposes, does the Hilliard image qualify as an accurate depiction of her facial features? No, it doesn't really, at least if the shape of

the nose is viewed as significant, and Isaac Oliver's miniature is certainly more accurate, if the detailed written accounts of

Elizabeth's appearance in the last years of her life are taken into consideration.

Please click on  to advance to Page 5.

to advance to Page 5.

Please click on  to return to the Index Page at The Face Of Bach.

to return to the Index Page at The Face Of Bach.

Please click on  to visit the Johann Sebastian Bach Index Page at Teri Noel Towe's Homepages.

to visit the Johann Sebastian Bach Index Page at Teri Noel Towe's Homepages.

Please click on the  to visit the Teri Noel Towe Welcome Page.

to visit the Teri Noel Towe Welcome Page.

TheFaceOfBach@aol.com

Copyright, Teri Noel Towe, 2000 , 2002

Unless otherwise credited, all images of the Weydenhammer Portrait: Copyright, The Weydenhammer Descendants, 2000

All Rights Reserved

The Face Of Bach is a PPP Free Early Music website.

The Face Of Bach has received the HIP Woolly Mammoth Stamp of Approval from The HIP-ocrisy Home Page.