The Search for the Portrait that Belonged to Kittel Pages at The Face Of Bach

The Queens College Lecture of March 21, 2001 - Page 5 - Codifying my Modus Operandi - Part 2 - The George Washington Iconography

The Face Of Bach

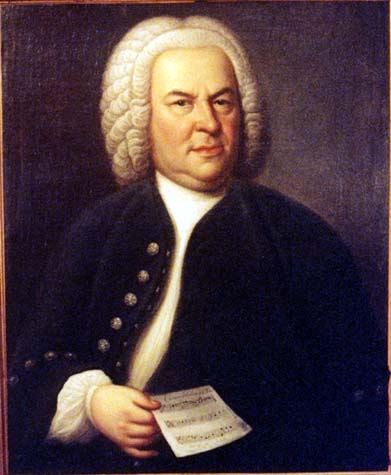

This remarkable photograph is not a computer generated composite; the original of the Weydenhammer Portrait Fragment, all that

remains of the portrait of Johann Sebastian Bach that belonged to his pupil Johann Christian Kittel, is resting gently on the surface

of the original of the 1748 Elias Gottlob Haussmann Portrait of Johann Sebastian Bach.

1748 Elias Gottlob Haussmann Portrait, Courtesy of William H. Scheide, Princeton, New Jersey

Weydenhammer Portrait Fragment, ca. 1733, Artist Unknown, Courtesy of the Weydenhammer Descendants

Photograph by Teri Noel Towe

©Teri Noel Towe, 2001, All Rights Reserved

The Search for the Portrait that Belonged to Kittel

The Queens College Lecture of March 21, 2001

Page 5

Codifying my Modus Operandi - Part 2

The George Washington Iconography

Issues of control over the image mandate a discussion of the apparent incongruities that can result from the collision of "official"

and "private" portraiture. The best examples for such a discussion, in fact for the discussion of the challenges posed by forensic

iconographical investigations in general, are the portraits of George Washington, not only because he sat frequently and usually

patiently for those who wanted to paint his portrait, but also because the depictions are extremely well documented. The

Washington iconography encapsulates all of the problems and all of the variables.

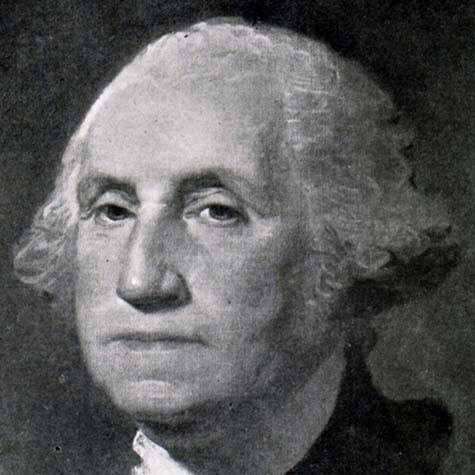

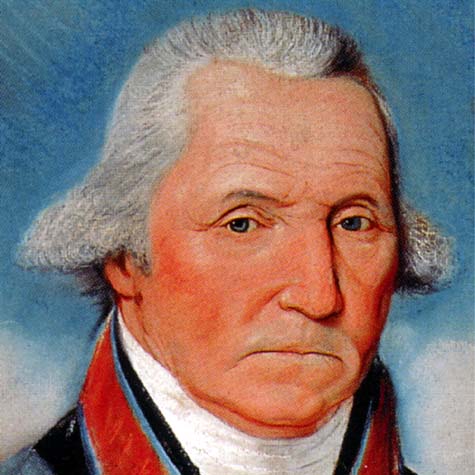

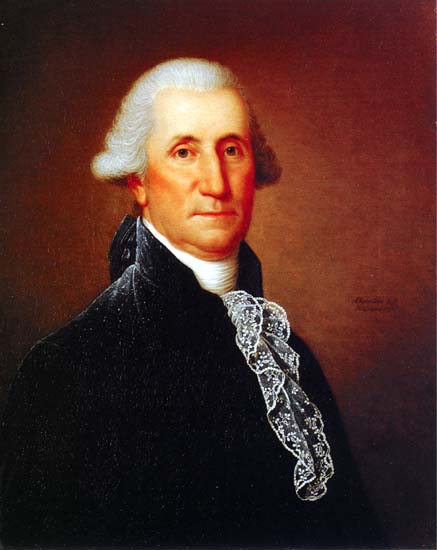

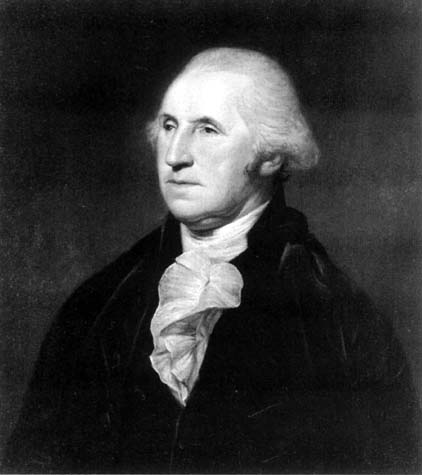

The image on the left is a detail from the so-called Virginia Regiment Portrait, painted on commission from Washington by Charles

Wilson Peale in 1772, when Washington was 40. It is the earliest known known depiction of him "from life". It was for him a

favorite image, and the original painting hung in a prominent place in Mount Vernon thoughout his lifetime. It also shows

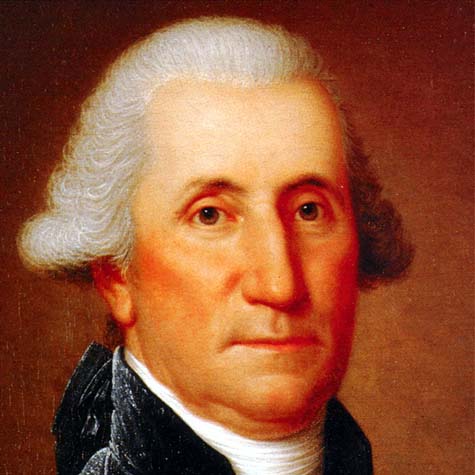

Washington while he still had some teeth in his jaws. The image on the right is a detail from the so-called Athenaeum Portrait that

Gilbert Stuart painted from life in 1796, a portrait that he deliberately never finished, and a portrait that he kept and used as the

model for almost every portrait he painted of Washington for the balance of his long career. (I say "almost" because the so-called

Lansdowne Portrait, which has been in the news recently, is also a direct life portrait and the progenitor of a number of exemplars

of that type.) By the time of those 1796 sittings for Gilbert Stuart, Washington was 64, was toothless, and was contending with a

new and uncomfortable set of false teeth.

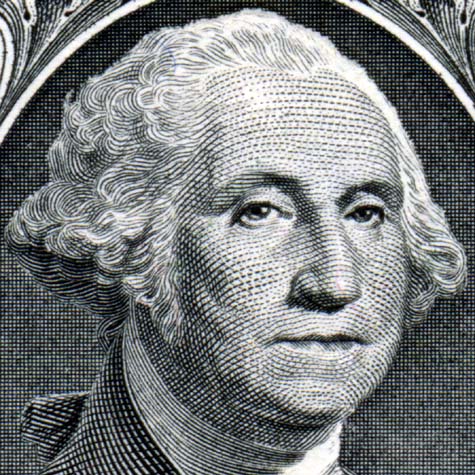

The Athenaeum portrait, of course, is the Washington of the One-Dollar-Bill, and, as early as the 1820s, it was being described as

the Washington that everybody thought of and copied by all and sundry to satisfy a seemingly insatiable audience.

Pretend, for a moment, that you had never seen the Virginia Regiment Portrait before, that the only documented image that you had

was the Athenaeum Portrait, and that you did not know that Stuart had commented that Washington's uncomfortable and ill fitting

false teeth had distorted the shape of his mouth. You are brought the Virginia Regiment Portrait to authenticate, and the only

provenance that you have is five generations of family tradition that the portrait was a wedding present from one of Washington's

step-grandchildren.

Not only do you have to contend with a face that is a quarter of a century younger, but also you have to contend with a face that

has a different dental configuration.

If that were the fact situation, I wonder how frequently the knowledgeable might dismiss the Virginia Regiment Portrait as not

authentic.

And since we're on the subject, a comparison of the Athenaeum Portrait with the version to be found on the One Dollar Bill yields

some interesting results, too:

First of all, the image on the One Dollar Bill has been "flopped", indicating that, as is so often the case with portrait prints, the

viewer is seeing what the sitter would see, looking into a mirror. Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, the Treasury Department

engravers have given the First President a touch of a face lift, a nip here and a tuck there, to make him look a bit younger, and they

also have made his mouth and jaw look a little less "stretched" than it is in the Athenaeum Portrait.

Here's another intriguing example:

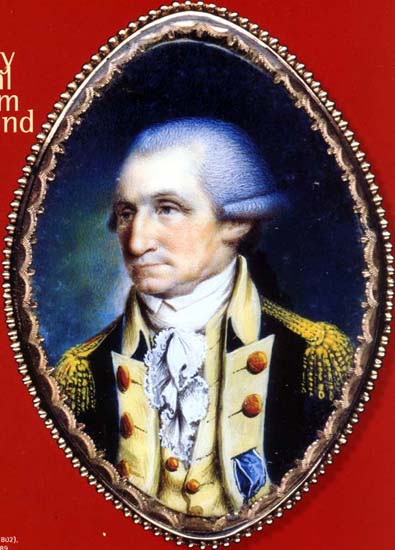

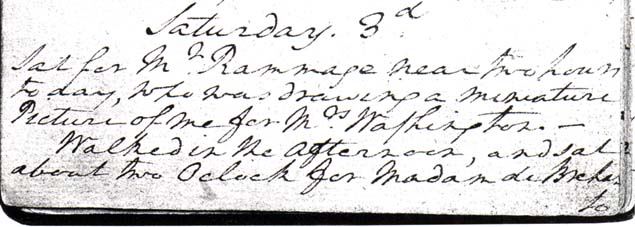

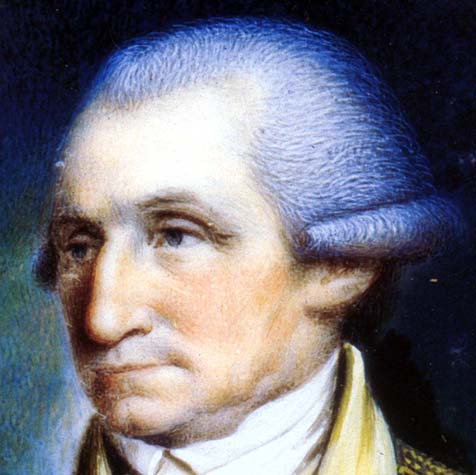

In the John Ramage miniature, a portrait which Washington commissioned as a keepsake to give to Martha in the fall of 1789, the

year in which his sole remaining tooth was extracted, the shape of the mouth graphically reflects the Father of Our Country's

toothless state. But he did not find anything wrong with the depiction, which Martha kept and treasured for the rest of her life.

However, John Ramage was not the only artist for whom Washington sat on October 3, 1789. We know from his diary that, after a

constitutional, he sat for Mme. de Brehan.

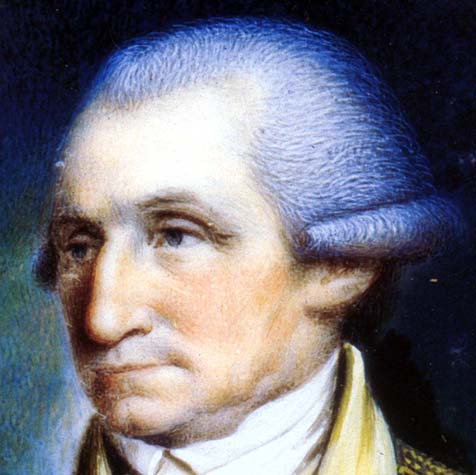

This is the heroic, idealized profile that Mme. de Brehan produced from the sitting with Washington that was held on the same day

as the Ramage sitting.

No matter how familiar with Washington's physiognomy, anyone who sees the two images side by side and is unaware that both

depict George Washington likely would think you daft if you asserted that not only do they depict the same individual but also that

they were drawn from life, on the same day.

Nevertheless, careful study shows that, apart from Mme. de Brehan's allowance for Washington's toothless state, the same

charateristic anatomical details, the ones that make Washington's face his, are very much in evidence, and that they are accurately

depicted in both images. These characteristics include the General's mild underbite, the unique arch of the nose, his distinctive,

somewhat bulbous left eye, and the unusual folds of the drooping left eyelid.

I doubt that you will be surprised to learn that Washington was pleased with the results of Madame de Brehan's labors, too. The

accuracy of the rendering of Washington's profile becomes of even greater interest when one compares Mme. de Brehan's

rendering of the First President's profile with the one done seven years later by the British artist, James Sharples:

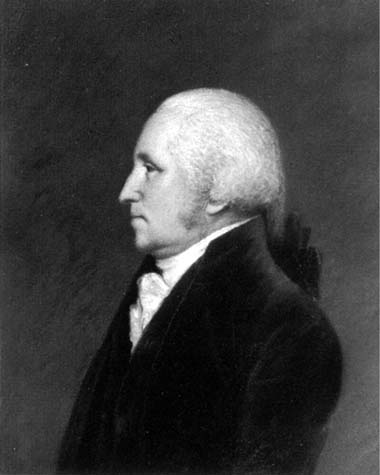

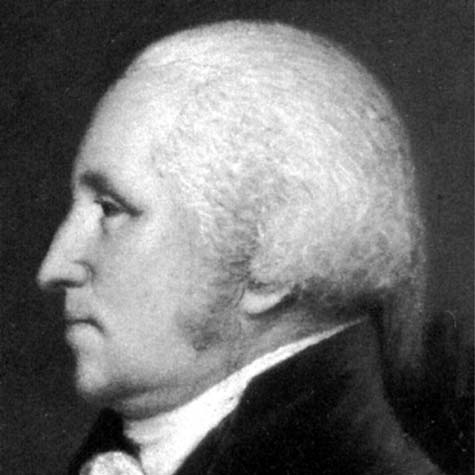

It so happens that one of the exemplars of the Sharples profile, the last portrait for which Washington sat, has come down with a

testimonial letter written by the General's step-granddaughter, who imparts important factual information about the accuracy of the

image. But, even without the information that Nelly Parke Custis provides, most importantly that the General apparently had finally

found a set of false teeth that fit him properly and also that Sharples took down the profile mechanically, using a physiognotrace,

careful study reveals that, yes, these two profiles are essentially accurate depictions of the same man. Furthermore, the comparision

indicates that either Mme. de Brehan did a spectacular job of mentally restoring the teeth to the President's jaws for the purpose of

her heroic and idealized profile or the President slipped in a set of false "choppers" between the Ramage sitting and hers.

As it happens, President Washington sat for his portrait a third time in October of 1789. He was in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and,

while visiting Harvard College, he sat for Edward Savage. The resulting portrait in oils, which was finished and dated the following

year, was described by the then president of Harvard College as the most accurate depiction that he had ever seen:

This wonderful image makes for an interesting comparison with the Ramage miniature, doesn't it?

If the General had been fitted with a full set of dentures by the time that he sat for these portraits, he does not appear to have had

them in his mouth on either occasion, does he?

The sittings for the Harvard portrait, incidentally, provided the basis for Savage's masterpiece, the group portrait of the

Washingtons, Martha's two grandchildren, and the President's manservant and confidant, Willy Lee. The monumental canvass, a

unique and extraordinary amalgam of the private and the public aspects of George Washington, was unveiled in Philadelphia on

Washington's 64th birthday, February 22, 1796:

Washington liked the result well enough that, two years later, when Savage and his colleague Daniel Edwin announced the

publication of a stipple engraving of the painting, he bought four of them, framed:

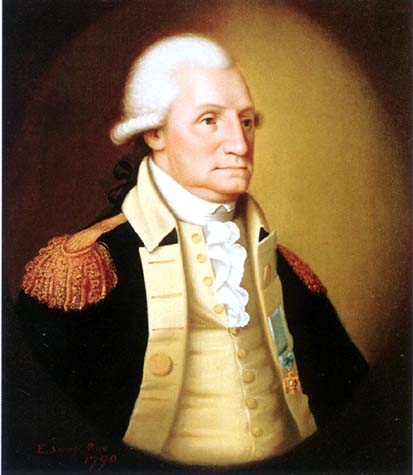

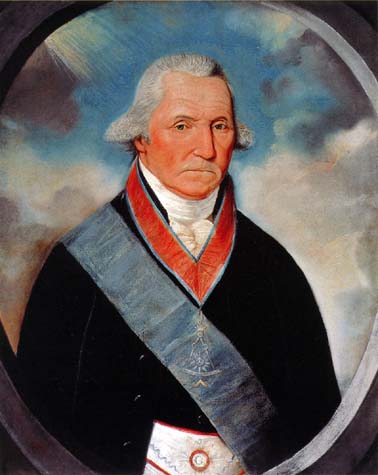

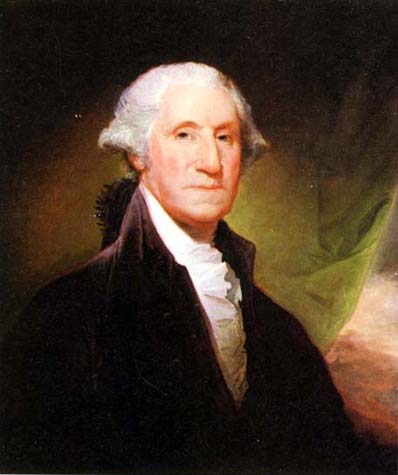

And finally, a group of portraits from 1794 and 1795, when Washington was 62 and 63, respectively.

First, let us juxtapose two all too rarely encountered portraits of Washington, portraits that were taken from life within weeks of

each other in 1794. On the left, a pastel portrait by Williams, for which Washington sat, a touch grudgingly, to satisfy a request

from the Masonic Temple in Alexandria, Virginia, of which he had been Grand Master. On the right, a portrait in oils by Adolf

Ulrich Wertmüller, who after a successful stint as a court painter to Gustav III of Sweden, painted portraits at the court of Louis

XVI, where he received particular praise for a portrait of Marie Antoinette. His patrons, and thus his income, disappeared with the

onset of the Reign of Terror, and he emigrated to the United States, to try his hand at building a clientele among the wealthy former

colonists. In the fall of 1794, Washington sat for Wertmüller, in Philadelphia. Several portraits resulted, of which this one, now in

the Philadelphia Museum of Art, appears to be the earliest.

The juxtaposition of these two images has a shattering impact on the viewer. Here are the two portrait heads, side by side:

Both depictions are masterpieces of detailed, realistic portraiture. But Williams was no sycophant and no Uriah Heep, and

Wertmüller was not only a magnificent portraitist in the manner of Pompeo Batoni but also a master ne plus ultra at the subtle

application of the Stridex™ Factor. Williams's depiction is unflinching, if not brutal, in its accuracy and completeness. To my

knowledge, which I confess is not as exhaustive as it might appear, Williams's is the only portrait of Washington to show the

smallpox scars on his nose, and the scar on the left cheek is clearly visible, much more so than it is the vast majority of the

portraits, including those by Gilbert Stuart. Wertmüller, on the other hand, accustomed to the demands of temperamental Swedish

and French aristocrats and nouveaux riches, "airbrushes" out the scar completely, while still faithfully recording the distinctive

contour of the General's left cheek. (This contour is distinctive, and can be traced along the border of the light and shadow in the

left facing "three-quarter" portraits like an interstate highway on a road map.) However, Wertmüller, like Williams, includes the mole

that Washington had on his right cheek, where the cheek meets the ear lobe. I believe that they are the only two artists to show this

blemish, but, to be fair, I have to observe that Washington eventually grew sideburns that were long enough to hide the mole.

There is an intriguing discrepancy between the two portraits which some of you already may have noticed. The eyes appear blue in

the Williams pastel and brownish in the Wertmüller oil. Cause for alarm? Not really. The written descriptions of Washington do not

agree on this point, and that does not surprise me. Eye color can vary to the viewer, in my experience, depending on the available

light.

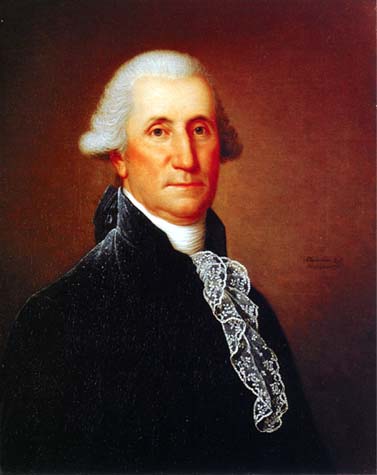

At first glance, when you see Wertmüller's portraits of Washington, you say to yourself, "That's Washington?" But, when you

juxtapose the Wertmüller portrait with the so-called Vaughan Portrait by Gilbert Stuart, which dates from 1795 and of which he

painted at least 12 exemplars (The one illustrated is the "master" image, now in the National Gallery in Washington, D. C.), it is clear

that the same man is depicted.

The distinctive elements of Washington's physiognomy are clearly and accurately depicted in Wertmüller's unjustly neglected

portrait. The brushwork is more detailed and more precise than it is in Stuart's well loved paintings, but both men have captured

accurately Washington's facial features - the eyelids, the curve of the nose, the taut lips and the underbite, the distinguishing crease

midway between the lower lip and the chin, although I must point out once more that Wertmüller, a court painter to the manor born,

an artistic diplomat, "airbrushes" out completely the scar on Washington's left cheek, a superb example of an application of the

Stridex™ Factor by a top echelon "portrait painter to the stars". It is little wonder, though, that Wertmüller's portrait was not well

received. Its elegant detail, its regal preciseness, right down to the hair powder that sullies Washington's black velevt coat like a

bizarre form of dandruff, had little appeal in the significantly more egalitarian culture of even the upper classes in the new Republic,

which preferred the more rough hewn, broader brushstroked approach of Gilbert Stuart. Wertmüller's portrait reeked of the

European and of the monarchical, if you will, and that subliminal effect was fatal.

In fact, there were even a few who complained about the accuracy of the likeness. Washington's step-grandson, George Washinton

Parke Custis did not think that it could be a portrait from life, and asked where the protruding lower lip was. I guess that it is all in

the eye of the beholder, but the protruding lower lip to me is every bit as much in evidence in Wertmüller's portrait as it is in

Savage's. (Please note, by the way, the absence of the mole from right cheek in the Savage portrait.)

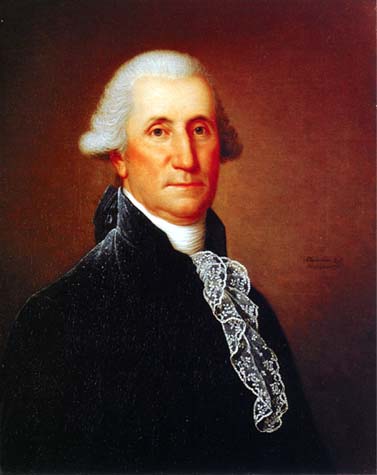

Before we leave the Wertmüller portraits and Gilbert Stuart's "Vaughan Model" series, let us consider the altogether too casually

used terms "replica" and "copy" in the context of these two sets of paintings.

Wertmüller is known to have made several exemplars of his portrait of Washington. If all of them are as identical as the one from

Philadelphia and the exemplar from the following year that is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, his portraits of Washington

could be described accurately as duplicates of one another.

The differences between the two, at least as far as the depiction of the facial features is concerned, are minimal.

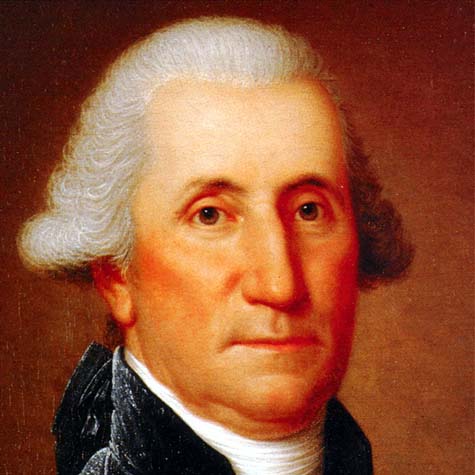

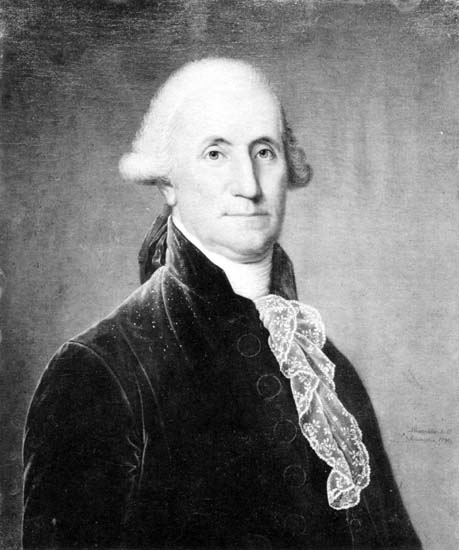

One cannot say the same thing when juxtaposing one exemplar of the Gilbert Stuart "Vaughan Model" portrait with another:

The right hand exemplar cannot fairly be described as either a "replica" or as a copy, although it is clearly a close variant of the

master image. These subtleties need to be remembered whenever one is called upon to assess the merits of an alternate version of a

known image, or to compare and contrast two versions of the same model or master image, like the two versions of the Elias

Gottlob Haussmann portrait of Johann Sebastian Bach, which, as far as I am concerned, clearly are the products of two separate

and distinct series of sittings.

Now, yet another pair of portraits of Washington that date from 1795.

The portrait on the left is the last that was painted from life by Charles Wilson Peale; the portrait on the right is the work of his son,

Rembrandt. Both paintings are the result of the same series of sittings, because Washington graciously permitted Peale, who, by

1795, had known Washington for almost a quarter of a century, to let three of his sons paint his portrait at the same time their father

did. Once again, at first glance, the reaction is: "That's the same man?" Once again, a careful comparison of the facial features

confirms that both are essentially accurate depictions of the facial feaures of the Father of Our Country. (I say, "essentially",

because to varying degrees, the Peales each have downplayed the scar on the left cheek.)

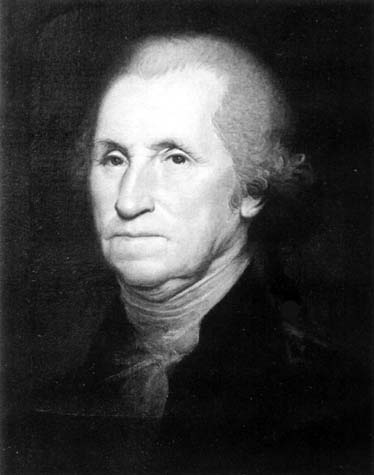

Finally, there is the omnipresence problem. The Washington of the Athenaeum Portrait, the Washington of the one dollar bill is the

one known best to all and sundry, and therefore it is the "official" face of Washington.

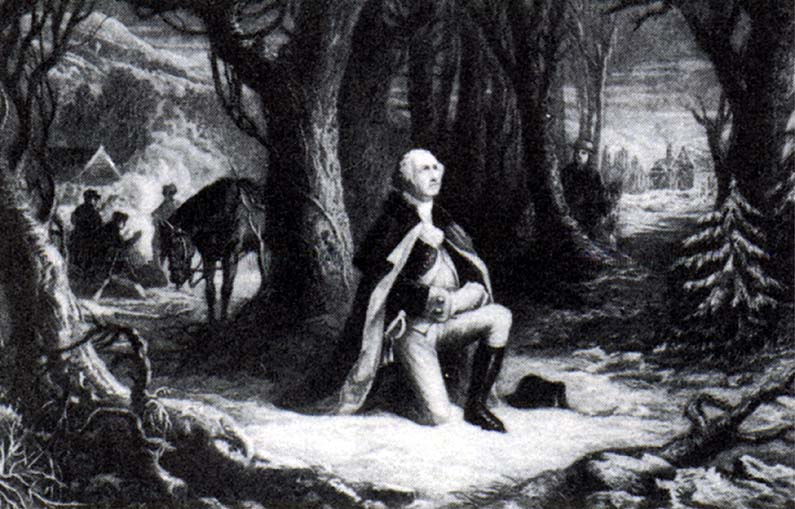

Consider this late 19th century popular print of Washington praying, during the bitter winter at Valley Forge:

The face and the hairstyle are that of the Athenaeum Portrait.

But, in reality, during the bitter winters at Valley Forge, Washington looked like this. This is the remarkable portrait of Washington

after the Battle of Princeton, that Charles Wilson Peale painted in 1780, when Washington was 48, for the General's longtime friend,

Elias Boudinot:

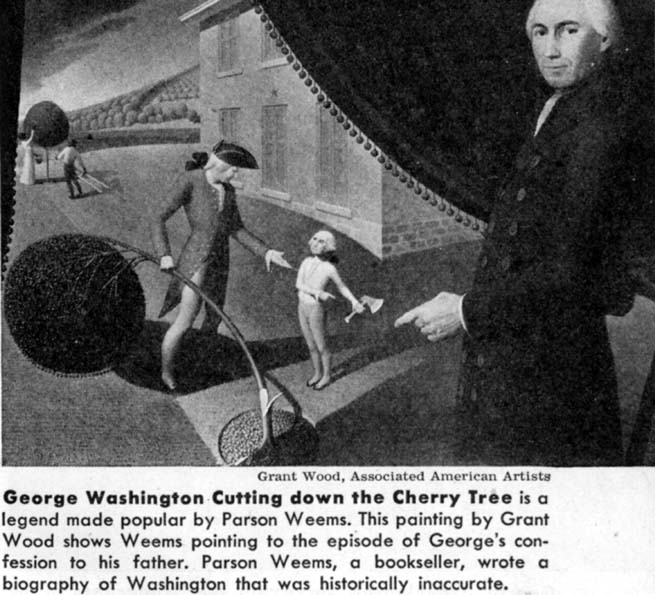

Grant Wood, one of the greatest American painters of the 20th century and the creator of American Gothic, innately understood the

omnipresence phenomenon, and he took full advantage of the general public's "bonding" to the Athenaeum-Dollar Bill Washington.

When he painted his mildly tongue-in-cheek interpretation of the discredited Parson Weems anecdote about Washington chopping

down the cherry tree, Wood gave the child Washington the Athaenaeum face and hair-do:

Now that I have explained just how delicate and how complicated a task it is to establish the standards that one has to use in

assessing the accuracy of the depiction of an individual's facial features for portrait authentication purposes, let me finally begin to

address the specific case of Johann Sebastian Bach.

Please click on  to advance to Page 6.

to advance to Page 6.

Please click on  to return to the Index Page at The Face Of Bach.

to return to the Index Page at The Face Of Bach.

Please click on  to visit the Johann Sebastian Bach Index Page at Teri Noel Towe's Homepages.

to visit the Johann Sebastian Bach Index Page at Teri Noel Towe's Homepages.

Please click on the  to visit the Teri Noel Towe Welcome Page.

to visit the Teri Noel Towe Welcome Page.

TheFaceOfBach@aol.com

Copyright, Teri Noel Towe, 2000 , 2002

Unless otherwise credited, all images of the Weydenhammer Portrait: Copyright, The Weydenhammer Descendants, 2000

All Rights Reserved

The Face Of Bach is a PPP Free Early Music website.

The Face Of Bach has received the HIP Woolly Mammoth Stamp of Approval from The HIP-ocrisy Home Page.