The Search for the Portrait that Belonged to Kittel Pages

at The Face Of Bach

The Queens College Lecture of March 21, 2001 - Page 3 - Enter the Weydenhammer

Portrait Fragment

The Face Of Bach

This remarkable photograph is not a computer generated

composite; the original of the Weydenhammer Portrait Fragment, all that remains of the

portrait of Johann Sebastian Bach that belonged to his pupil Johann Christian Kittel, is

resting gently on the surface of the original of the 1748 Elias Gottlob Haussmann Portrait

of Johann Sebastian Bach.

1748 Elias Gottlob Haussmann Portrait, Courtesy of William H. Scheide, Princeton, New Jersey

Weydenhammer Portrait Fragment, ca. 1733, Artist Unknown, Courtesy of the Weydenhammer

Descendants

Photograph by Teri Noel Towe

©Teri Noel Towe, 2001, All Rights Reserved

The Search for the Portrait that Belonged to Kittel

The Queens College Lecture of March 21, 2001

Page 3

Enter the Weydenhammer Portrait Fragment

Little did I know.

Enter what I have come to call the Weydenhammer

Portrait Fragment.

The Internet is indeed an amazing innovation.

On April 2, 2000, during the year in which the world marked

the 250th anniversary of the death of Johann Sebastian Bach, a lady who had seen my homepage on the Bach portraits

e-mailed me:

Dear Mr. Towe,

If I had your address, I could supply you with yet another portrait of J. S. Bach, or,

more precisely, a portrait fragment (alas just the head) slightly larger than life. It has

been our family since the 1870's when our ancestors emigrated from the Leipzig area.

Of course, I was interested, and I immediately e-mailed her

my business address. A few days later, just hours before I left for Washington, D. C., to

attend the Biennial Meeting of the American

Bach Society, the photos arrived at the offices of Ganz & Hollinger, the law firm at which I am

"Of Counsel".

Sitting in the office of my long-time law partner,

Jeri Hollinger, I slid the 4x6 prints out of the padded envelope that she had handed to

me, and this is the first image that I saw:

"Oh, my God!", I exclaimed softly.

Jeri asked me what the matter was, and I simply showed her

the photo. "That's a picture of

Bach", she said.

And I replied: "Yes, I know. And I think I

know which one."

The photographs were accompanied by a handwritten letter,

dated April 3, 2000, which reads, in pertinent part:

"Dear Mr. Towe,

This fragment has been in the family since my mother's family came to this country. I had

no idea that portraits of the great man were so scarce. My wish was that somehow the face

could be reunited with the rest of the painting if that were extant -- and also to find

out something more about it -- the artist?. The family tradition was that it was painted

by an ancestor.

Anyway, I think the painting is wonderful and hope you

will agree.

Looking forward to hearing from you."

Oh, yes! I did, and do, agree! The painting is wonderful!

I also realized that I might at last be at the end of a

personal quest that at that time had lasted some 37 years, that a personal "Holy

Grail" might at last have been found. I did not have the presence of mind to fetch

Prof. Neumann's hefty tome from the shelves before heading to the Metroliner and the American Bach Society meeting, but

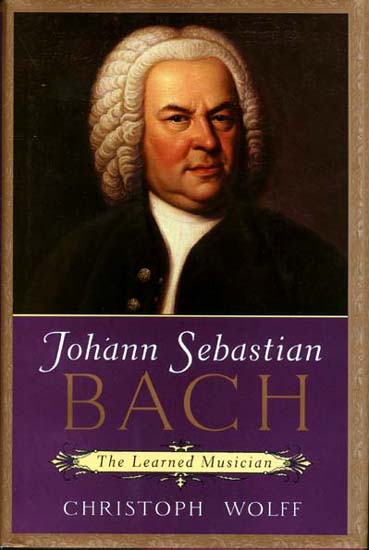

I did have my copy of Christoph Wolff's superb new biography, Johann Sebastian Bach, The

Learned Musician, with me. As many of you I am sure already know, the dustjacket

for the book is illustrated with the upper portion of the 1748

Haussmann Portrait:

I spent the trip down alternating between reading

Christoph's masterful, perceptive, innovative, and elegantly written acount of Bach's life

and comparing the 4x6 snapshot with the dust jacket detail from the 1748

Haussmann Portrait.

That comparison only reinforced my initial reaction: The

fragment is what remains of the portrait of Bach that belonged to Kittel. While at the American Bach Society meeting, I

had a bit of fun pulling the snapshot out of my jacket pocket and asking my colleagues,

"Does this man look like anybody we know?" Only one wrinkled up his nose and

walked away in disgust when I explained what it was alleged to be. A couple of others

asked what the provenance was, but no one seemed especially enthusiastic.

But I knew. And I was sure. I had not forgotten the words

of Bernard Berenson, as relayed by Robert Koch, the distinguished art historian whose

courses in Netherlandish Painting of the Renaissance and The Art of the Print I had taken

at Princeton 30 years and more before: "The

first ten seconds are worth the next ten years."

I know that face, and it is that same face, albeit younger

and thinner. He may not look quite the way I had expected him to, but it is that same

face.

My confidence was such that I asked the owners of the

painting for permission to reproduce it in black and white and announce its existence in

my autobiographical entry in the Class Book for my then forthcoming 30th Reunion at

Princeton. They were very gracious and gave me the go-ahead, and, no matter what, copies

of that volume are bound to rank among the more unusual bits of Bachiana!

Those who know me well know that I am unabashedly, if

selectively, superstitious, and that I put great stock in anniversaries. After I was

reminded by Christoph Wolff's observation in Johann Sebastian Bach, The

Learned Musician that Kittel was living with the Bachs as a boarding pupil when

Bach died and that he was certainly among those who followed his casket to its interment

in the Johanniskirchof on July 31, 1750, I asked the owners of the painting for permision

to announce the existence of the painting, via the internet. They agreed, and on July 31,

2000, the website called The Face Of Bach came into

being. There was a great deal of initial excitement and enthusiasm, and two distinguished

magazines that I know of -- The American Organist and The Strad -- made

mention of the announcement.

But, by that time, the exhilaration and the euphoria had

worn off, and stark reality had usurped their places.

Based not only on my knowledge of the face of Bach but also on my familiarity with both

the documentary evidence and the acknowledged authentic images, I was firmly convinced

that the long lost portrait of Bach that had belonged to Kittel at long last had been

found, but, obviously, I could not expect my colleagues and the world at large to

"take it on faith". I still had to prove it to them and to the world.

I realized that I now had to codify my method. I now had to "formalize" the

unwritten criteria that I had developed for my own use over the years, the procedures that

I had come to follow after years of study and analysis.

For, you see, Bach's is not the only face that I have

studied so intently.

I have had a lifelong interest in portraits, period. My

fascination with portraiture dates to small childhood, and my interest perhaps was kindled

by two portraits in oils that hung in the family apartment:

The portrait on the left, of James Thornhill, is by Pompeo

Batoni, and it now graces my dining room. The portrait on the right, of Barbara St. John

Bletsoe, the second wife of the Fifth Earl of Coventry, is by Angelica Kauffmann, but it

now hangs in the Art Museum at Princeton University,

to which I gave it in 1998, as a memorial to my beloved Mother and Father, who made it

all possible.

It was as a child of seven, going on eight, that I first

learned that portraits were not necessarily accurate and that they did not necessarily

depict the individuals that they were alleged to depict. I learned my first real lessons

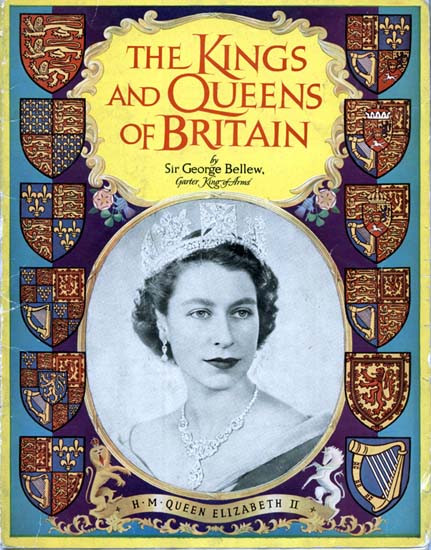

about the unreliability of portraiture from the ca. 1954 edition of Sir George Bellew's

Pitkin book, The Kings and Queens of Britain, which was given to me during my

first visit to London:

Sir George Bellew was then the holder of the ancient and

arcane position of Garter King of Arms, and, as such, was responsible for all things

heraldic in Great Britain as well as the planning and organization of the Coronation of

Queen Elizabeth II in 1953.

I am sure that it will come as no surprise to anyone that

Sir George was a stickler for both detail and accuracy, and the illustrations that he

selected for the remarkable little book of sketches that he wrote of every monarch from

King Egbert through Queen Elizabeth II reflect his high standards. The first inkling that

I had that portraits of historical figures are often not what they seem came from a

"sidebar" on page 6:

The delicate and diplomatic wording notwithstanding, the

message was clear. We don't know what most of the British monarchs really looked like

until 1399. And Sir George was very cautious and very diplomatic in

selecting and in providing captions for the British monarchs who preceded King Richard II.

Here are two examples:

In fact, Sir George's reluctance to foist inaccurate

depictions of any of the British monarchs upon any unsuspecting and impressionable reader,

like me, ultimately led to the omission of all such "speculative" portraits from

a later edition of the book, which I bought when I visited London in 1966.

Of course, I am indebted to Sir George Bellew, and it is a

pleasure to acknowledge him and to thank him for having planted those seeds of doubt in

the psyche of an eager second grader. Unbeknownst to him and to me, he got me started on

the right foot. Consciously or subconsciously, I always recalled his admonition and his

words of caution, whether studying the stern and chiseled features of the diorite statue

of Kha-ef-re, the builder of the Second Pyramid at Gizeh and the Sphinx, in the Musée des

Antiquitées in Cairo, or the magnificent Velazquez portrait of Pope Innocent X in the

Galeria Doria-Pamphili in Rome.

It's quite a question, isn't it?

Just how do you determine if a portrait really depicts the

person who it is said to depict, particularly when the person died long before the advent

of photography?

When one is seeking to authenticate a hitherto unknown image alleged to depict a specific

individual, particularly when that image does not have documented provenance, the

fundamental issue, the question that takes precedent over all others, is:

Can the image be shown to be an accurate depiction of the facial features, as they are

agreed to be, of the alleged subject of the image?

All other issues are secondary, really, until this question is addressed and answered as

fully as is possible.

Please remember that an image that is fully documented and that has impeccable provenance

can also be an image that is not an accurate depiction of the subject's facial features.

To give a facetious example, a Crayola® crayon drawing that Chelsea Clinton made of her

father while in nursery school might have perfect provenance, but the accuracy of her

rendering of his facial features is almost surely going to be far less than perfect.

First of all, one must collate all of the acknowledged images of the subject and assess

their accuracy, one by one, making a careful and detailed inventory of the distinctive

characteristics to be found in each image, and, equally importantly, how those

characteristics change with the passage of time. If there are any detailed written

descriptions of the subject's facial features, these must also be taken into account. For

example, if a written description indicates that the individual in question had a large

mole on his left cheek, as Handel did, for instance, and it is not to be seen a painting

or a drawing that is alleged to depict him, one has to address the question and determine

if the absence of the mole can be explained in a way that does not threaten to undermine

what otherwise seems to be an accurate depiction.

Establishing these standards is not necessarily an easy task.

Please click on  to advance to Page 4.

to advance to Page 4.

Please click on  to return to the Index Page at The Face Of Bach.

to return to the Index Page at The Face Of Bach.

Please click on  to visit the

Johann Sebastian Bach Index Page at Teri Noel Towe's Homepages.

to visit the

Johann Sebastian Bach Index Page at Teri Noel Towe's Homepages.

Please click on the  to visit the

Teri Noel Towe Welcome Page.

to visit the

Teri Noel Towe Welcome Page.

TheFaceOfBach@aol.com

Copyright, Teri Noel Towe, 2000 , 2002

Unless otherwise credited, all images of the Weydenhammer Portrait: Copyright, The

Weydenhammer Descendants, 2000

All Rights Reserved

The Face Of Bach is a PPP Free Early Music

website.

The Face Of Bach has received the HIP Woolly Mammoth Stamp of Approval from The HIP-ocrisy Home Page.