|

|

Bach Books |

|

B-0221 |

|

|

Title: |

Bach's Musical Universe: The Composer and His Work |

|

Sub-Title: |

|

|

Category: |

Analysis |

|

J.S. Bach Works: |

|

|

Author: |

Christoph Wolff |

|

Written: |

|

|

Country: |

USA |

|

Published: |

Mar 2020 |

|

Language: |

English |

|

Pages: |

432 pages |

|

Format: |

HC |

|

Publisher: |

W. W. Norton & Company |

|

ISBN: |

ISBN-10: 0393050718

ISBN-13: 978-0393050714 |

|

Description: |

A concentrated study of J.S. Bach’s creative output and greatest pieces, capturing the essence of his art.

Throughout his life, renowned and prolific composer J.S. Bach articulated his views as a composer in purely musical terms; he was notoriously reluctant to write about his life and work. Instead, he methodically organized certain pieces into carefully designed collections. These benchmark works, all of them without parallel or equivalent, produced a steady stream of transformative ideas that stand as paradigms of J.S. Bach’s musical art.

In this companion volume to his Pulitzer Prize–finalist biography, Johann Sebastian Bach: The Learned Musician, leading Bach scholar Christoph Wolff takes his cue from his famous subject. Wolff delves deeply into the composer’s own rich selection of collected music, cutting across conventional boundaries of era, genre, and instrument. Emerging from a complex and massive oeuvre, Bach’s Musical Universe is a focused discussion of a meaningful selection of compositions―from the famous Well-Tempered Clavier, violin and cello solos, and Brandenburg Concertos to the St. Matthew Passion, Art of Fugue, and B-minor Mass.

Unlike any study undertaken before, this book details J.S. Bach’s creative process across the various instrumental and vocal genres. This array of compositions illustrates the depth and variety at the essence of the composer’s musical art, as well as his unique approach to composition as a process of imaginative research into the innate potential of his chosen material. Tracing Bach’s evolution as a composer, Wolff compellingly illuminates the ideals and legacy of this giant of classical music in a new, refreshing light for everyone, from the amateur to the virtuoso.

85 illustrations |

|

Comments: |

|

|

Buy this book at: |

HC (2020): Amazon.com | Amazon.co.uk | Amazon.de

Kindle (2020): Amazon.com | Amazon.co.uk | Amazon.de |

|

|

Source/Links:

Contributor: Aryeh Oron (May 2020) |

|

|

Discussions - Part 1 |

|

Christoph Wolff: Bach's Musical Universe: The Composer and His Work |

|

William L. Hoffman wrote (May 15, 2020):

As the third decade of the 21st century begins, the study of Bach is stimulated with major new publications. Foremost is Christoph Wolff's new Bach musical study, Bach's Musical Universe: The Composer and His Work,1 from probably the leading Bach scholar whose other significant previous contributions (all published by W. W. Norton) include the magisterial biography, Johann Sebastian Bach: The Learned Musician, 2000 (Update 2013), and The New Bach Reader: A Life of Johann Sebastian Bach in Letters and Documents, 1999 (see https://www.amazon.com/s?k=Christoph+Wolff+Bach+books&i=stripbooks&ref=nb_sb_noss). This is an unparalleled trilogy involving Bach 1999 scholarly English-language documentation with an updated commentary from Wolff; the most significant new biography with an emphasis on the formative, learned influences as well as new information across the breadth and depth of Bach studies; and now the companion study of Bach's music within narrative and biographical context, focusing on the major collections of instrumental and vocal music.2

Bach's Musical Universe explores most of Bach's music as found in collections compiled chronologically by Bach and fully revealed from this perspective for the first time. The eight chapters with prologue and epilogue focus on the introductory "On the Primacy and Pervasiveness of Polyphony," Bach's compositional calling card; eight chapters on the music: 1. "Revealing the Narrative of a Musical Universe" (Works List 1750), 2. "Transformative Approaches to Composition and Performance" (Three Unique Keyboard Works), 3. "In Search of the Autonomous Instrumental Design" (Toccata, Suite, Sonata, Concerto), 4. "The Most Ambitious of All Projects" (sacred Chorale Cantata Cycle), 5. "Proclaiming the State of the Art in Keyboard Music" (Clavier-Übung, four published keyboard exercises), 6. "A Grand Liturgical Messiah Cycle" (oratorios: John, Matthew and Mark Passions; Christmas, Easter, Ascension), 7. "In Critical Survey and Review Mode" (Late Revisions, Transcriptions, Reworkings: "Great 18" and Six "Schübler" Chorales for Organ, Harpsichord Concertos, Kyrie-Gloria Masses, Well-Tempered Clavier Book II), and 8. "Instrumental and Vocal Polyphony at Its Peak" (Art of Fugue, Canons and Musical Offering, B-Minor Mass), and closing "Praxis cum theoria" (Maxim of the Learned Musician). About the only music lacking in Wolff's new Bach book are the organ works and various sacred and secular cantatas, motets, and individual instrumental works. Wolff did oversee the cantatas as part of a three-volume German study of essays that he solicited from leading Bach scholars and edited, Die Welt der Bach-Kantaten (https://www.abebooks.co.uk/book-search/title/kantaten/author/christoph-wolff/), with only the first edition published in English (Amazon.com), covering the early sacred cantatas from Arnstadt to Köthen time.3

Bach's Business Card

Wolff (https://www.bach-cantatas.com/Lib/Wolff-Christoph.htm) traces his interest in Bach to his early studies in Germany emphasizing the medieval period and Bach's organ works while having an interdisciplinary background in the humanities, with research in Bach's musical library (http://bach-cantatas.com/Topics/Concerts-3.htm: "Re: Bach Network Dialogue Meeting"). His reputation was built on his PhD studies of stile antico in Bach's late works, a fundamental discipline previously neglected by Bach scholars, Der stile antico in der Musik Johann Sebastian Bachs: Studien zu Bachs Spätwerk, (Wiesbaden, 1968).4 This interest continues at the beginning of his current Bach musical study, Prologue, "On the Primacy and Pervasiveness of Polyphony: The Composer's Business Card." Bach lacked a university degree but more than compensated in his collected works which are musical treatises instead of the writings of theorists becoming popular in the 18th century Baroque period (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_music_theorists#18th_century). Bach's most learned works were composed and published in the 1740s when in 1747 he became a member of the distinguished Mitzler Corresponding Society of Musical Sciences, which included other distinguished composers such as Telemann, Stölzel, Handel, and C. H. Graun (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lorenz_Christoph_Mizler). The ostinato figure in Bach's Triple "portrait" canon, BWV 1076, Wolff calls Bach's "Business Card" (Prologue 7ff) and which originated in Bach's Goldberg canonic theme in the Anna Magdalena Notebook (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=15ezpwCHtJs) and found in his E. G. Haussmann society portrait ( https://www.bach-cantatas.com/thefaceofbach/QCL07.htm). This identifies Bach as the composer of the recent Goldberg Variations and the Well-Tempered Clavier (WTC, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hms_PF_CKV4), says Wolff (Ibid.: 7ff), and the master of "all-embracing polyphony" ( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johann_Sebastian_Bach#Counterpoint), and "the most hidden secrets of harmony," "unusual melodies: and "ingenious ideas."

Obituary: Print, Manuscript Works

The first accounting of Bach's compositions is found in his 1750 works list that was part of his Obituary and includes a summary description of his few published works as well as the bulk of his musical library, manuscripts of church music and instrumental works. This two-page catalog was compiled by Emanuel Bach, second-oldest son and based in Berlin, and was for the next century the only published overview. Emanuel's source was the music shelves in his father's Leipzig office, says Wolff in Chapter 1, "Revealing the Narrative of a Musical Universe: The First List of Works from 1750" (Ibid.: 15) which he summarily examined at the time of Sebastian's funeral, 29 July. It was an accounting of the musical estate to be distributed among his heirs in the fall. The published works in chronology order are: the four Clavierübung (http://bach-cantatas.com/NVD/Keyboard-Music-Mature.htm), 1731-41; the Six Schübler Chorales, BWV 645-50 (1746), for organ; Canonic Variations on "Vom Himmel hoch," BWV 769 (1747); The Musical Offering, BWV 1079; and The Art of Fugue, BWV 1080 (1751).

The largest section was the unpublished autograph manuscripts which Bach as Leipzig cantor had stored in shelves with dividers, beginning with the church pieces of cantatas probably sorted by church year main services so that he could access them for reperformances. The score and parts bound in wrappers were bundled and tied so that the score incipit stood out — listing the occasion, title, and scoring. Only three cantata cycles are extant, as well as a dozen other pieces, stacked chronologically from last to first composed. Eldest son Friedemann as estate executor returned from Halle in the fall of 1750 to divide the music, beginning with the cantatas. The estate division pattern, based upon provenance, shows that Friedemann inherited the bulk while the two generally took either the score with extra parts or the parts set, the exception being the second (unfinished) chorale cantata Cycle 2, the score going to Friedemann and the parts to his step mother, Anna Magdalena, who donated them to the Thomas School in order that she and her underage children could remain in the cantor's quarters until the end of the year. None of the three cycles was enumerated but the chorale works were identified by score incipit.5 The order is verified in Emanuel's 1790 estate catalog listing his entire inheritance, with the essential incipit information of church year service, incipit, scoring, and Cycle 1 or 3.

Sacred Vocal, Instrumental Works

Beyond the cantatas, the other vocal music was listed in categories, beginning with a section of special observances such as sacred festivals with oratorios, Masses, Magnificat, single Sanctus, funerals, and wedding Masses as well as secular dramas, serenades, and music for name days and birthdays. The next categories were five Passions and several double-choir motets. Not listed but later found in Emanuel's estate were the 18 sacred cantatas of cousin Johann Ludwig Bach that Sebastian had copied and performed during the third cycle in 1726 and the Bach Family Alt-Bachisches Archiv of musical manuscripts. The special sacred works were divided between the two oldest sons while copies may have gone to other family members. The instrumental works followed with organ music (preludes, fugues, etc), six trios (BWV 525-30), chorale preludes and the unfinished Orgel-Büchlein (Little Organ Book, BWV 500-644); then the keyboard works including the collections of WTC, toccatas, suites, inventions and sinfonias; the instrumental works of six sonatas each for solo violin and solo cello, sonatas for harpsichord and violin, and the harpsichord concertos, and finally "a lot of instrumental pieces, of all sorts, and for all kinds of instruments" (Ibid.: 16). While the large single vocal works were generally divided between the two oldest sons, few of the instrumental autograph manuscripts survive. Various copies were found among Bach family members, students, and associates such as Anna Magdalena's autograph of the solo violin and cello works, as well as the partial autograph of the "Great Eighteen Chorales," and the Bach autograph of the solo harpsichord concertos (BWV 1051-57).

Wolff's discussion of "Benchmark Works" (Ibid. 20f) identifies 11 groups of works "following the traditional scheme of opus collections" such as the three keyboard collections discussed below, the four published Clavierübung (Keyboard exercises), and the four late (1740s) published studies cited above. Other collections include the six Brandenburg Concertos and the four dozen chorale cantatas (1724-25, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chorale_cantata_(Bach)), which "not only involve extensive serial planning, but as a set of exemplar models. Wolff also cites the large single vocal works that also "possess opus character by nature, in their sizable structure and topical focus," that is the six oratorios cited above and the Mass in B-Minor. "Instrumental or vocal, the opus-style collections and the major works embody genuine landmarks," says Wolff (Ibid.: 24). These "milestones reflect Bach's very own way of mapping an ever-expanding space that epitomizes a musical universe encompassing his entire oeuvre, but with quite a few momentous markers standing out." Often, Bach dealt with certain genre, such as the keyboard suites of the six each English, French, and Partitas and moved on, likewise with the three oratorio Passions. Embedded in these works are Bach's unparalleled compositional legacy of the prelude and fugue and the four-part chorale.

Three Köthen Keyboard Collections

In order to demonstrate his abilities to teach music as part of the duties of cantor in Leipzig, including keyboard and composition, Bach had assembled at Köthen in early 1723 for his Leipzig probe three exemplary practical textbooks of keyboard music "inventions," each quite distinctive, which he then applied to his students at the Thomas School, observes Christoph Wolff in an essay:6 1. Orgel-Büchlein; 2. the Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 1, BWV 846-69; and 3. the Aufrichtige Anleitung (Faithful Guide) book of 15 each sinfonias and inventions, BWV 772-801. These three served both as learning tools to play the keyboard as well as to "acquire a foretaste of composition," says Wolff (http://bach-cantatas.com/NVD/Keyboard-Music-Early.htm). Although never published, these three manuscript fair-copy collections with descriptive titles "would explain their instructional utility and impress the Leipzig authorities," sayWolff in Bach's Musical Universe, Chapter 2, "Transformative Approaches to Composition and Performance" (Three Unique Keyboard Works (Ibid.: 28). The autograph collections of "imaginative musical instruction" (Ibid.: 29), provide materials for performance and study materials for general compositional principles," says Wolff (Ibid.: 34), involving four-part chorale settings for organ and counterpoint, Bach's great compositional legacy. In the title pages, the term Anleitung (guide) is found in titles 1 and 3, titles 2 and 3 are addressed to lehr-begierige (those eager to learn) while 1 and 2 refer to anfahende Organisten (beginning organists) and advanced musicians. Each group emphasizes varied genres: 1. 45 chorale prelude settings using organ pedal obbligato, 2. 24 Preludes and fugues, 3. 15 each two and three contrapuntal lines played in a cantabile manner.

Orgel-Büchlein: Chorale Preludes

The Orgel-Büchlein (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orgelbüchlein, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=whnTkKiXqM0) was Bach's first musical study, begun in Weimar in 1708 with space for 164 chorales in the manuscript listed by incipit in order of the various seasons of the ecclesiastical year, beginning with Advent through the experiences of Christian life. It is the "most comprehensive extant group of organ chorale settings on the classic Lutheran hymns from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries," says Wolff (Ibid.: 35). It "functioned as a guidebook for text-bound composition, with emphasis on concrete word-tone relationships and content-specific musical expression," he says (Ibid.: 37). This incomplete but "consummate masterpiece" focused on "inspiring and testing musical imagination" (Ibid.: 43f) with "associated texts that invite a wide spectrum of musical expression" in "mostly four-part contrapuntal scores" and was "absolutely consequential for his process as a composer." Most of the 45 settings involve hymns for the first half of the church year, de tempore (from time to time), the life of Jesus Christ. It has settings in the initial de tempore (Nos. 1-60) section for 26 of the first 27 chorales, Advent to Passiontide, omits 13 of the next 26 (Nos. 27 to 51), Easter through Pentecost, but has none of the nine succeeding Trinity Time and festival designated chorales. In the omnes tempore (all the time) section, Nos. 61-164, only 10 chorales are set (designated BWV 635-644) of the more than 100 systematically listed by theme.7 Some of the chorale gaps were filled in the even earlier, more concise chorales in the Neumeister Collection, BWV 1090-1120, that Wolff discovered in the 1980s (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neumeister_Collection). Besides the concise chorale preludes, Bach in Weimar began composing the extended "Great Eighteen Chorale Preludes," BWV 651-668 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Eighteen_Chorale_Preludes) and in Leipzig in 1739 he published his Clavierübung III, German Catechism chorale collection in varied styles and genres (http://www.bach-cantatas.com/NVD/BWV669-689-Gen1.htm, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bRl-q-gV7xc). The early organ chorale preludes helped to establish the basis for the varied treatment of chorales in the Clavierübung III and the cantata cycle in the chorale choruses, chorale tropes, and chorale arias.

Well-Tempered Clavier Book 1

The other two autograph manuscript collections deal with counterpoint settings for harpsichord as sketched beginning in 1720 in Friedemann's little clavier notebook. Eleven preludes (without fugues) which became part of the Well-Tempered Clavier Book 1 ( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Well-Tempered_Clavier), may have been part of Bach's original plan when he was jailed for four weeks in Weimar in late 1718, dismissed to become capellmeister at Köthen, while drafting "roughly one prelude and fugue per day," Wolff calculates (Ibid.: 46). They were arranged in rising key order, chromatic major and minor (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nPHIZw7HZq4), to determine temperaments and tonality while exploring "in depth the ramifications of two fundamentally different kinds of free and strict musical composition in juxtaposition: the improvisatory prelude and the contrapuntal fugue," he says (Ibid.: 49), each "should be understood as a composition in its own right," as "exemplary models." The preludes show a uniform motivic structure, a construction principle similar to the Little Organ Book, "yet on a larger scale," he says (Ibid.: 50). "Tempo, rhythmic patterns, metric devices, and other features all contribute to compositional diversity," he notes (Ibid.: 51). They "stand as novel, innovative, and extremely inventive kinds of preludes, which in some ways foreshadow the expressive character pieces of a later generation." As compared "to the capricious improvisatory fancy that shapes the preludes," the paired fugues in the same key show a strict procedural approach in fugal composition, "embracing all the theoretical and practical aspects." The "preexisting conventions are elevated to an unparalleled level of compositional sophistication and musical variety," showing "the threefold combination of imaginative fecundity, intellectual penetration of the compositional task, and performing ability," he notes (Ibid.: 52). Both books of the WTC were widely disseminated after 1750 in manuscript copies by Bach students and groups most notably in London, Berlin, and Vienna where Baron Gottfried von Swieten and others introduced them to Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. The WTC "represents the composer's first truly significant work," says Wolff (Ibid.: 53). It created the "acceptance of major-minor tonality, new forms for free and strict composition, and unrestricted utilization of the four-octave chromatic scale, and a full-developed range of keyboard idioms and textures" in "an era that delighted in systematic, encyclopedic endeavors."

While much lesser known than the WTC, the collection of 15 each keyboard Inventions and Sinfonias, BWV 772-801 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inventions_and_Sinfonias_(Bach), emerged initially as a performance teaching device and later with the three-part Sinfonias as a compositional study. The music was originally labeled "Praeambulum" and "Fantasia" as part of a program of instruction for Friedemann. It was the first pedagogical teaching exercise in which both father and son made entries involving motivic development and canonical response, says Wolff (Ibid.: 54), with the autograph fair copy completed in early 1723. The music achieved its tonal configuration and ascending chromatic organization as well as its final, more descriptive contemporary terminology. The entire collection now called a "Faithful guide," was designed with various purposes to teach and encourage playing while developing a sense of concentrated contrapuntal writing with two and three voices, both considered "inventions" in the sense of "good ideas" "in the form of distinct musical subjects," he says (Ibid.: 58). The rhetorical "inventio" in two voices offers a subject worthy of learning and performing, "Bach's most important prerequisites for study and composition." Bach took the multifaceted term "sinfonia" for the three voices from the Greek symphonia (concord of sound) to show their "distinctive contrapuntal makeup" based on triadic harmony. Bach "had entered completely unchartered territory," Wolff suggests (Ibid.: 59), the music becoming "freely-invented, concise, and distinct ideas" "in strongly unified but contrapuntal settings" with equal voices imitating singing style, "often shapeby the interplay of a concise subject with its countersubject." Bach would never again compose such a collection since it already created "the general principles of contrapuntal writing" which "became an ever more essential aspect of the fabric of his instrumental and vocal scores," he says (Ibid.: 60).

Bach used the two clavier collections as the foundation to teach students in Leipzig. Private pupil Heinrich Nicolaus Gerber much later recalled that at his first lesson, Bach had him play in succession the Inventions, the French and English Suites, and the WTC. The three original workbooks embraced the teaching Bach desired: integrating composition and performance, "their transformational function, and their complementary value as sources of musical recreation and intellectual nutrition for future generation of students," says Wolff (Ibid.: 63). The organ chorales "advanced the means of both musical expression and the techniques of pedal playing." The harpsichord preludes and fugues employed "the essence of modern tonal harmony, the shift toward equal temperament, and the use of the thumb as part of the total hand playing to play chromatic keys. The Inventions and Sinfonias married compositional and analytical study while "introducing the play of polyphonic music in a distinctly transparent way and in an aesthetically pleasing cantabile manner." The three workbooks, unique and individually designed collections, "established new standards for both composition and performance and in different areas," revealing ingenious and forceful originality, technical mastery, and intellectual control" in Bach's musical language,"with its ultimate goal of moving the heart."

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

1 Christoph Wolff, Bach's Musical Universe: The Composer and His Work (New York: W. W. Norton, 2020), Amazon.com; contents, Google Books.

2 Another rewarding pictorial-biographical study is Wolff's 2018 Bach. A Life in Pictures (http://barenreiter.epartnershub.com/Bach-A-Life-in-Pictures-Hardback-5102280000.aspx).

3 Christoph Wolff ed., The World of the Bach Cantatas, Vol. 1, "Early Sacred Cantatas https://unm.on.worldcat.org/search?queryString=no:36179013#/oclc/36179013: View Description, Contents; Vol. 2, Bach's Worldly Cantatas; Vol. 3, Bach's Leipzig Church Cantatas (Amazon.com, Rochester User Services).

4 See stile antico extract, Chapter 8, "Bach and the Tradition of the Palestrina Style." In BACH: Essays on his Life and Music (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1991: 84ff), Google Books. 5 An important recent writing is Yo Tomita's "Manuscripts," in Part 1, Sources, The Routledge Research Companion to Johann Sebastian Bach, ed. Robin A. Leaver (London: Routledge, 2017: 47-88), https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315452814.ch3; "Bach's Own Classification" (p. 57) suggests that a Johann Elias Bach letter "hints that a large number of cantatas from the two missing annual cycles may already have been removed from Bach's library in 1740." 6 Christoph Wolff, "Apropos Bach the teacher and practical philosopher," in The Keyboard in Barque Europe, ed. Christopher Hogwood (Cambridge University Press, 2003, 93ff), Festschrift for Gustav Leonhardt. 133ff).

7 The current Orgelbüchlein Project involves the setting of the 118 chorales (http://www.orgelbuechlein.co.uk/the-missing-chorales/) lacking in Bach's collection (http://www.orgelbuechlein.co.uk). Bach also composed a collection of 186 free-standing chorales, BWV 253-483 (http://www.bach-cantatas.com/Vocal/BWV250-438-Gen4.htm, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_chorale_harmonisations_by_Johann_Sebastian_Bach).

—————

To Come: Bach's Musical Universe, Chapter 3-5, instrumental music, chorale cantata cycle, keyboard exercises. |

|

Julian Mincham wrote (May 15, 2020):

[To William L. Hoffman] Thanks for the review Will. I have just ordered a copy. |

|

Jeffrey Solow wrote (May 15, 2020):

Very informative and helpful review - thanks! |

|

|

| |

|

Instrumental: Multi-Movement Toccata, Suite, Sonata, Concerto |

|

William L. Hoffman wrote (May 26, 2020):

In Bach's first unified keyboard collections, called the Aufrichtige Anleitung (Faithful Guide) and assembled in Köthen for Leipzig use, the movements for teaching and performing were blueprint miniatures of instrumental music that would be expanded to multi-movement works in succeeding collections: the Orgel-Büchlein chorale preludes to form "The Great 18" liturgical hymns and the Clavierübung III German Catechism chorale collection in varied styles and genres, the Well-Tempered Clavier (WTC) Book 1 multi-sectional preludes and fugues to help shape later keyboard studies such as suites and sonatas, and the contrapuntal Inventions and Sinfonias that would help to stimulate the groundwork for some concerto movements. These and other collections were part of Bach's endeavor "In Search of the Autonomous Instrumental Design," the title of Christoph Wolff's Chapter 3 in his new Bach's Musical Universe.1

Initially, Bach for his autonomous instrumental design studied "prevailing repertories that had long occupied keyboard performers and composers alike," he observes (Ibid.: 65). "Initially and in particular this meant the large toccatas in the manner of his much admired north German idols," Dietrich Buxtehude https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dieterich_Buxtehude#Preludes_and_toccatas) and Johann Adam Reincken https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johann_Adam_Reincken). Bach "also was drawn to the increasingly popular [multi-sectional, three movements and more] genres of suites, sonatas and concertos, which dominated European instrumental music during the first half of the eighteenth century." All of Bach's works in these categories followed "extant formal models," maintaining "the well-established parameters of the prevailing forms" that "carefully selected additions to these various genres emphatically stress the idioms of his distinct musical language as it emerged in the early1700s," he says (Ibid.: 65).2

Each genre of multi-sectional works would impact Bach's wider compositions as well as influence succeeding composers in the Classical era and beyond. The benchmark collections materialized initially in Cöthe, "bolstering the keyboard core with two different sets of suites [English, French], then branching out into two books of unaccompanied solos [sonatas and partitas] for violin and violoncello, and eventually embracing multi-movement orchestral concertos, beginning with the six Brandenburg Concertos, BWV 1046-51, and evolving into the early Leipzig years in the six Sonatas for Harpsichord and Violin, BWV 1014-19, and Six Trio Sonatas for Organ, BWV 525-530. The music displays both affirmation and perfection. There were a few exceptions in son Emanuel Bach's Obituary works catalog of his father in 1750, Wolff finds (Ibid.: 65): the collection of harpsichord concertos, BWV 1052-59, and the Brandenburg Concertos. "Still, the known manuscript collections surely represent a mere fraction of the composer's total instrumental output, as many surviving individual works indicate — a situation compounded by the many specific losses resulting from the division of Bach's estate in 1750," Wolff cautions (Ibid.: 65f). Based upon the costs of paper, copying, and binding in Cöthen, Wolff estimates in his Bach biography3 "the assumed losses would exceed 200 pieces" during Bach's tenure there (1718-23). "He clearly considered his instrumental opus collections a more or less final word in every category, and he decided each time to move on rather than add another comparable opus," says Wolff (Ibid.: 66), the sole exception being the WTC Book 2 in the 1740s. His most demanding critic of his own work, while a student of other composers, notably Telemann, Vivaldi, and François Couperin, Bach "never recast the conceptual and formal patterns of suites, sonatas, and concertos in order to suit his own distinctive resolve," says Wolff (Ibid.: 66f). His ambition was "to eclipse and outclass his models in terms of internal refinement, textural riches, and depth of expressive character," he says (Ibid.: 67).

While Bach achieved notoriety as a keyboard performer, he also was skilled as a string player with the violin, viola, and "probably the violoncello as well," suggests Wolff (Ibid.: 67). Bach's teacher, Wolff surmises, was his father, Johann Ambrosius Bach (1645-1685), a skilled violinist and leader of the instrumental ensemble at St. George's church in Eisenach. At the Saxe-Weimar Court (1708-18), Bach first was organist and then concertmaster in 1714. Initially, Bach excelled on the organ and harpsichord, became a distinguished organ appraiser and builder, and visiting virtuoso. He also expanded the uses of the harpsichord , organ, and later, the fortepiano," says Wolff (Ibid.: 69).

Early Harpsichord Toccatas, BWV 910-16

First and formative was Bach's youthful collection of seven keyboard toccatas. The very early singular, multi-sectional manualiter (without pedal) toccatas would become in part introductory preludes found in the organ preludes and fugues composed across Bach's career (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_organ_compositions_by_Johann_Sebastian_Bach). These playful toccata works, also known as preludes, caprices, or improvisations, were probably composed before 1710, and are influenced by Buxtehude's preludes," says harpsichordist Anthony Newman.4 They show the influence of Johann Jakob Froberger's Italianate toccatas and Buxtehude's organ preludes. Among these works, he says, are the earliest, S.913; the best-known with seven movements, S.912; the simplest, S. 914; the most brilliant, S. 915; and the most dazzling fugue, S. 916 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jTtnScn5j-U). Wolff cites the influence of Buxtehude's chorale fantasia, "Nun freut euch," BuxWV 210 (Ibid: 69, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MuabwssACN8). The toccatas particularly show the stylus fantasticus, observes Wolff (Ibid.: 70), a technique important to Ton Koopman, who, "In his interpretations, he looks for the stylus phantasticus fantasia freedom elements, variation of registration and tempo, as well as Bach's cantabile way of playing, although he occasionally likes to speed up the tempo, as Bach did ("Ton Koopman: Bach Student, Champion," http://bach-cantatas.com/NVP/Koopman-T-Profile.htm: paragraph beginning "Considering Bach's organ works").

No autograph score of the toccatas survives while early and late versions are found in the "Möller Manuscript" and "Andreas Bach Book" of Bach older brother Johann Christoph of Ohrdruf (1671-1721, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johann_Christoph_Bach_(organist_at_Ohrdruf)). The first six toccatas, listed in the 1750 works catalog, have the multi-sectional layout of the north German toccata (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toccatas_for_Keyboard_(Bach)), alternating fast (fugal) and slow (Adagio) sections with a beginning passagio, each averaging 12 minutes. The seventh, BWV 916, has the Italian concerto three-movement model of Presto, Adagio, and Allegro (fugue) and was inserted "around or after 1710," says Wolff (Ibid.: 72). The direct Buxtehude models are BuxWV 164 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YRPRcDXz6Jo) and BuxWV 165 ( https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2jPZ5Yu4vU8). While Bach adopts the framework of these models, "he also exceeded them in every respect: in sheer technical virtuosity, significantly expanded format, number of contrasting sections, overall contrapuntal design, and in particular, the complexity of the fugues," says Wolff (Ibid.: 74). The set of six toccatas "exhibit, above all, a special fascination with large-scale form" and is found in organ works such as the Passacaglia in C minor, BWV 582 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ie52xH8V2L4).

English Suites, BWV 806-11; French Suites, BWV 812-17

Bach's first systematic, mature collections of large-scale instrumental works are the dance partitas for harpsichord, known as the six "English" Suites, BWV 806-11, and the six "French" Suites, BWV 812-17. Influenced by the growing civic galant culture, they observe the traditional dance framework, following prelude, with allemande, courante, sarabande, and gigue, with inserted pairs of other dances, called galanterie, that precede the closing gigue. These two suites were shaped in Cöthen after the three collections of singular contrapuntal keyboard settings, called Aufrichtige Anleitung (Faithful Guide), of miniatures of chorale preludes, prelude and fugues, and inventions and sinfonias (see "Christoph Wolff: Bach's Musical Universe," https://groups.io/g/Bach/topic/74220413: "Three Köthen Keyboard Collections"). The two suite collections show three keyboard national styles: German traditional contrapuntal, the dance "so loved in France," and "fantastic" (Italian), Davitt Maroney says (Ibid.: 14f).5 The earliest of the "English" suite dates to Weimar about 1715 and puts emphasis on the opening preludes or overtures and "most likely written for his private use and for teaching his sons and other pupils," says Maroney. The nickname "English," origin unknown, may relate to Bach's use of the dance suite pioneered by Charles François Dieupart (1667-1740, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Dieupart), "London-based from about 1702/3, and was much appreciated by his English clientele," says Wolff (Ibid.: 78).

Both "English" and "French" nicknames are first found in Berlin sources after 1750 in manuscript copies and have comparable musical goals of teaching and performing multi-sectional works, moving "well beyond the achievements of the toccata opus," Wolff says (Ibid,: 82). In binary form, each dance "its own distinctive character" and go "far beyond" the Dieupart model. The "French" Suites were begun in the 1722 Anna Magdalena Clavier Büchlein and, in contrast to the earlier "English" Suites, are more compact, varied, and irregular," he says (Ibid.: 80). Bach "felt he had a greater liberty in the suite form than in the sonata," says Henri Jarriè.5a To the inserted minuet, gavotte and bourrée in the "English" Suites, Bach in the "French" Suites added the new, more fashionable galanterie types: air, loure, and polonaise, Wolff says (Ibid.), "creating a singular melody for the top voice of every dance type," he observes (Ibid: 83). Bach also applied "repeatedly integrating strains of counterpoint" with "harmonic twists" and "rhythmic-contrapuntal animation," he says (Ibid.: 84). "This general procedure became a hallmark, comparably applied later on in sonata and concerto scores," while the "great variety of dance movements proved to be a decisive resource for the technical design and expressive character building of arias and choruses," he notes (Ibid.: 85), in the Cöthen serenades.

Unaccompanied Solos for Violin, Cello, BWV 1001-12

Among Bach's instrumental works, the solos of six each unaccompanied for violin, BWV 1001-06, and cello, BWV 1007-12, have become legion, ranking with the keyboard WTC collections that are still being studied today. His first non-keyboard opus collections focused on the single voice rather than the now popular sonatas and partitas for string instruments and basso continuo, including the Corellian trio sonata for two voices with continuo. By 1720, Bach had completed the first book of three sonatas and three partitas for violin (autograph fair copy), "soon joined by a companion book of six cello solos" (suites), says Wolff (Ibid.: 85). Inspired by arrangements of Vivaldi violin concertos as transcriptions for organ (BWV 592-6) or harpsichord (BWV 972-87) and "trio sonatas designed for several players into one-man shows for the organ," says Wolff (Ibid.: 86), Bach in Cöthen sought "to test the limits of what was possible within the framework of autonomous instrumental design, free of support by any kind of accompaniment, making the violin and cello "study objects in musical independence." Bach's initial violin model was the two solo violin suites of Weimar violinist Johann Paul von Westhoff (1656-1705, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johann_Paul_von_Westhoff), while "no model Bach would have known existed for the violoncello suites." "Even though no draft of these solo violin works have survived, the challenges of the project suggest a fairly long gestation period, of perhaps a decade or so," Wolff suggests (Ibid.: 87). The actual composition began about 1718/19 and Bach's title of "Libro Primo" (https://www.bach-digital.de/rsc/viewer/BachDigitalSource_derivate_00005334/db_bachp0967_page001r.jpg) implies that the cello opus would be next. These two collections "were widely disseminated before 1800," he says (Ibid.: 89).6

The violin solos were played by "one of the greatest violinists," says Emanuel in 1774, not identified, says Wolff (Ibid.: 90), but possibly one of three: Johann Gottlieb Graun (1703-71, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johann_Gottlieb_Graun), teacher of Friedemann 1726-27 and Berlin colleague of Emanuel; Franz Benda (1709-86, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Franz_Benda), Berlin colleague of Emanuel; and legendary Johann Peter Salomon of Bonn (1745-1815, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johann_Peter_Salomon). The violin opus (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sonatas_and_Partitas_for_Solo_Violin_(Bach)) contrasts three four-movement sonatas (chiesa: slow-fast-slow-fast) and three "very irregularly structured suites in the Italian guise of partita (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Partita), with preludio or allemande, corrente, sarabande, bourrée, gigue, chaconne and in the third, BWV 1006, added loure, gavotte, and menuet. Most notable is the extended Chaconne closing Partita, BWV 1004, with 64 variations, achieving numerous transcriptions (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Partita_for_Violin_No._2_(Bach)). The music probably was performed in Cöthen by concertmaster Joseph Spieß, at the Leipzig Collegium musicum by Dresden violinist Johann Georg Pisendel, Bach himself, and Salomon in Berlin, Wolff suggests (Ibid.: 90f).

"In their formal makeup, the two collections show equally original approaches," says Wolff (Ibid.: 91). Book 1 for violin "shows the contrasting juxtaposition of two distinct genres," the sonata and suite, with the three Corellian-style sonatas showing progressive polyphony in the first three movements with a second movement fugue and "warmly lyrical third," closing with a rapid finale as each movement "displays a highly individual profile," he says (Ibid.: 92). In contrast, the three violin partitas each have a different makeup and number of movements, each with its own unique character, in contrast to the uniform earlier English and French Suites and the latter (Book 2) unaccompanied cello suites and published six Partitas in Clavier-Übung I (1725-31, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Partitas_for_keyboard_(Bach)). Beyond these five collections of instrumental suites, Bach essayed the solo suite form only a few more selective times: in the Flute Partita in A minor, BWV 1013 (http://bach-cantatas.com/NVD/BWV1030-1035-Gen3.htm: "The unaccompanied Flute Partita, BWV 1013"), and in the four Lute Suites, BWV 995-7, 1006a (http://bach-cantatas.com/NVD/BWV995-1000-Gen2.htm).

Bach in the solo cello suites systematically placed pairs of "minuets, bourrées, and gavotte between the sarabande and gigue in all the suites," he observes (Ibid.: 93). Bach favored the suite genre of all six works (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cello_Suites_(Bach)), giving this makeup and appeal to the unique unaccompanied cello music that shows "in idiomatic fashion the distinct characteristics of a variety of setting types."7 The arpeggiated prelude of Cello Suite 1 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1prweT95Mo0) "may be understood as a congenial cello response" to the iconic opening prelude in C of the WTC Book 1, BWV 846a (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ToWj_4xvVZA), he says. Also in contrast to the solo violin, Book 1, Bach favored less harmonic implications and use of chords while giving each cello movement a unique character such as the exceptional Sarabande of the Suite No. 5 in C minor (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sg_-K2S1fX0), "the most abstract and compelling rendition of this grave solo dance that Bach ever conceived," he says (Ibid.: 94).

Meanwhile, Bach in his solo violin and cello suites "forged an unprecedented idiomatic," "all- embracing polyphony" (Vollstimmigkeit), says Wolff (Ibid.: 97). Later, Bach created arrangements of three unaccompanied string solos: the Harpsichord Sonata in D minor, BWV 964 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EzvwZj50lmM), based on the Violin Sonata in A minor, BWV 1003 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hPSH5Hut9Ug); the Lute Suite in G minor,BWV 995, transcribed from the Cello Suite No. 5 in C minor, BWV 1011 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xhJuSU6C1e0); and the Cantata 29 Sinfonia (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tDsrw5PRqyU), adapted from the Preludio of the Violin Partita in E Major (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5tjl07RmEQg). Collectively, the "two books of violin and cello solos elevate the levels for both composition and performance to unparalleled heights," he observes (Ibid.: 98). "In line with their singular designs, multipurpose potentiality, and variety of expressive characters, the two collections benefit conceptually from the collective experience gained from" the three Cöthen keyboard collections, Aufrichtige Anleitung (Faithful Guide, https://groups.io/g/Bach/topic/christoph_wolff_bach_s/74220413?p=,,,20,0,0,0::recentpostdate%2Fsticky,,,20,2,0,74220413), and the two sets of keyboard suites."

Brandenburg: Six Concertos for Several Instruments

While in Cöthen Bach had the luxury and opportunity also to create "six different and essentially unparalleled concertos, placing them together to form an opus" says Wolff (Ibid.: 99). "They apparently belonged to a larger body of individual concertos of various kinds from the Weimar and Cöthen years, a repertoire that no longer exists as such," as Bach exploited the potential of a fine orchestra as well as visiting soloists. Remnants exist of the initial Brandenburg Concerto No. 1, known as the extended Sinfonia in D major, BWV 1046a=1071 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vrz8LRaL2Qk, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kG8EzJtqoeI), which originally opened the Hunting Cantata 208 of 1713, and the original version of Brandenburg Concerto No. 5, BWV 1050a (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gtAdBjZhfA4), as well as later Bach arrangements of opening movements as sinfonias in cantatas: Concerto No. 1 in F Major, BWV 1046, opening Cantata 52 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F4eKluZCAfs), and Concerto No. 3 in G Major, BWV 1048, in Cantata 174 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4vym2jSr4UU, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=scrT3jOE0Yo).

In the late 1730s, Bach also adapted Brandenburg Concerto No. 4 in G Major, BWV 1049 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zHyzQf38F6w), replacing the solo violin, as Harpsichord Concerto No. 6 in F Major, BWV 1057 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_abEuZWVEsM). After 1730, he also adapted three keyboard movements (Prelude and Fugue, BWV 894, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cSbOcpcQWio; and the Adagio from Trio Sonata in F, BWV 527/ii, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hMepl2Jfv1E), for the Triple Concerto in A minor for flute, violin, and harpsichord, BWV 1044 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SqUohKkQ5A4), the same concertino soloists as the Fifth Brandenburg Concerto. From the rich store of now-lost Cöthen instrumental music, it is possible that Bach had available another Brandenburg-style concerto, No. 7 in G Minor (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZQ9yjy1_4QE), surviving as the Viola da Gamba Sonata in G Minor, BWV 1029 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=84P3Kr1-miE). The "Sonata No. 3 in G minor for Gamba," BWV 1029, may be an arrangement of a concerto (or trio sonata) for two flutes (or flute and oboe) about the same time as the Brandenburg Concertos (by 1722), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-JcWlgH9pLI.

The "colorful instrumental combinations" in the Brandenburg Concertos, BWV 1046-51,9 were influenced in part by Bach's "background and experience as organist" using various stops to explore the rich and varied sound, he says (Ibid.: 100). Based upon Bach's earlier experience in Weimar with Vivaldi's string concertos and their ritornello form, adapted for keyboard, as well as the "tonality-driven principles," Wolff says (Ibid: 103), Bach forged a new type of concerto that displays the musical rhetorical concepts of order (Ordung), coherence (Zusammenhang), and proportion (Verhältnis). "More than any other type of musical setting, concerto composition concretized these seemingly abstract principles," he says (Ibid.).

Sonatas for Harpsichord and Violin

Although Bach had no responsibilities to compose instrumental works when he took the cantor's post in Leipzig, "most of his extant ensemble and orchestral works actually originate from the Leipzig Years, and were written primarily for use at the Collegium Musicum10 concerts he directed from 1829-41," says Wolff (Ibid, 103), in the last section of Chapter 3, "Early Leipzig Reverberations," which deals with the two collections, six Sonatas for Harpsichord and Violin, BWV 1014-19, and the six Trio Sonatas for Organ, BWV 525-30. Like the Brandenburg Concertos, the set of six duo Harpsichord-Violin Sonatas were missing from the 1750 Obituary list, amended by Emanuel in 1774. The earliest extant copy dates to 1725 and a later copy by son-in-law Johan Christoph Altnikol, dating to the late 1740s, shows that the music continued to be performed and improved. The music of the first five sonatas is in the form of the four-movement sonata da chiesa (slow-fast-slow-fast) and may have been performed during church service communion, as well as the cello suites. The slow movements are in a progressive, sensitive style while the fast movements "excel in their discursive thematic-motivic development," says Wolff (Ibid.: 107).

"Further manuscripts from the Bach circle indicated that this sixth piece [BWV 1019] underwent major changes to its movement structure around 1730, and then again in the late 1730s," Wolff says (Ibid.: 107f), with five palindrome (mirror) movements (fast-slow-fast-slow-fast).11 This sonata "passed through four distinct versions," says Stephen Daw, 12 with three alternative movements, most notably a central Cantabile, ma un poco adagio (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=leu111oA_yU), drawn from sacred Cantata 120 about 1728/29 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9RhcjqXCl8A). This sonata in particular demonstrates three essential Bachian concepts: unity through diversity of mixed genres, dialogue between violin and harpsichord, and extension from conventional sonata design to trio texture. Bach gave the keyboard an "independent function," especially in the slow movements, with free, style, mixed textures, and polyphonic devices, says Wolff (Ibid.: 109), "so as to achieve clearly differentiated and idiomatic writing styles for the two instruments." Having achieved "a new type of duo sonata with an elaborate keyboard part — a clavier trio," Bach composed "no further such violin pieces," content to improve existing music," he says (Ibid.: 110).

Six Organ Trio Sonatas

The harpsichord-violin sonatas in the category of instrumental trios "do not exemplify it in its pure form," says Wolff (Ibid.), but was achieved at the same time in the "Six trios for organ, with obbligato pedal, BWV 525-30 (Obituary works list https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Organ_Sonatas_(Bach), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JmgT1-pVc-U). The strict three-part writing Bach had first achieved in Cöthen in his Sinfonias, BWV 787-801 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Eq1-TNv7rp8), and earlier in Weimar with the groundwork laid in his transcriptions of Italian-style concertos, BWV 592-96 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=saMWpMMPuu0), says Wolff (Ibid.: 110f). The collection of a single-player trio is found in the extant autography fair copy of c1730, "as a touchstone collection for his pupils, "he says (Ibid.: 112). These trio settings as part of "the signature genre of Bach the organist," also are found instrumental trio sonatas, freely composed sonatas, and chorale preludes in trio format, such as the "Great 18 Chorales" (Wolff, Ibid: Chapter 7, 253-57). Here in the organ sonatas, Bach achieves distinct treatment of all three parts, showing technical demands "without precedent," he says (Ibid.: 113). At least some of the sonatas "seem to have consisted of or incorporated actual transcriptions of sonatas for two solo instruments and basso continuo," he says (Ibid.: 113), dating to chamber sonatas in Cöthen or earlier. They embrace in Bach "three layers of history": organ recital practice, concertos and sonatas on a single [keyboard] instrument, editing and polishing with "the endpoint of a novel opus," he shows (Ibid.: 114), conceived in the middle to late 1720s. Bach also utilized the aria-like ABA da capo structure with development in the middle section of polyphonically-conceived opening and closing movements, flanking slow movements with "sensitive and embellished melodic lines." Without figured bass, these realized organ sonatas are manifested in Haydn string quartets without keyboard accompaniment, he points out (Ibid.: 113). Meanwhile, Bach continued to adapt various trio settings, most notably in his late published opus (c1747), the Six "Schübler" Chorales for organ, BWV 645-50 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schübler_Chorales, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YBOUVYrNKyk), transcribed from vocal trio arias in his chorale cantatas. 13

Addendum: Bach scholar Michael Marissen has just produced a recording discography, "24 favourite Bach instrumental works," https://open.spotify.com/playlist/0kRK8vRqq7xC6ScSaT2ujz.

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

1 Christoph Wolff, Bach's Musical Universe: The Composer and His Work (New York: W. W. Norton, 2020), Amazon.com; contents, Google Books.

2 For the most recent perspectives, see David Ledbetter, "Instrumental and Ensemble Music," in The Routledge Research Companion to J. S. Bach, ed. Robin A. Leaver (London: Routledge, 2017: 317-57), Google Books; see especially sections on "Analytical Approaches: Style" (327-32), and "Work Groups" and "Summary" (335-57) — some pages omitted.

3 Christoph Wolff, Johann Sebastian Bach: The Learned Musician, updated ed. (New York: W. W. Norton, 2013: 200), Google Books.

4 Anthony Newman, "Bach Toccatas for Harpsichord, liner notes (Englewood Cliffs NJ: Vox Music Group, 1995), Amazon.com.

5 5a Davitt Maroney, "La Musique de clavecin: English Suites" liner notes (Arles: Harmonia Mundi, 1999: 14f), Amazon.com; Henri Jarriè, "French Suites": 15).

6 A study of scholarly sources and theology is found at "Bach Chamber Music: Works for Solo Violin & Solo Cello - Discussions, http://bach-cantatas.com/NVD/Chamber-Solo-Discussion.htm).

7 <<While the Six Sonatas and Partitas for Unaccompanied Violin, BWV 1001-1006, have found considerable favor in the concert hall and beyond, the six cello suites also have found numerous applied versions in the visual arts8 with movies such as Master and Commander (Yo-Yo Ma) and The Pianist (Dorota Imiełowska), television's The West Wing, various popular recording anthologies, and ringtones (http://www.bach-cantatas.com/NVD/BWV1007-1012-Gen3.htm). Dancers who have choreographed the Bach music include Mikhail Baryshnikov-Jerome Robbins (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HicqwLT7WgY), Rudolf Nureyev, Mark Norris and Taiwan's Cloud Gate Dance Theatre. Selective, some movements have been played as memorial music for the Boston Marathon victims (Sarabande, BWV 1011/4), Katherine Graham, and Edward Kennedy (Sarabande BWV 1012/4). Yo-Yo Ma in his video of the six cello suites employs six artistic collaborations involving Kabuki artist, etchings, garden design, choreography, ice dancers, and filmmakers (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inspired_by_Bach). Ma's third versions of the suites, "Six Evolutions," is currently underway (NPR).>>

8 See Eric Siblin, The Cello Suites: J. S. Bach, Pablo Casals, and the Search for a Baroque Masterpiece (New York: Grove Press, 2009: 6ff).

9 A discussion of the Brandenburg Concertos, "Unity Thru Diversity," is found at http://bach-cantatas.com/NVD/BWV1046-1051-Gen4.htm).

10 Bach's Collegium Musicum repertoire includes four Orchestral Suites (Overtures), BWV 1066-69); the Violin Concerto in A minor, BWV 1041; the Double Violin Concerto, BWV 1043; and the Triple Concerto, BWV 1044. The Violin Concerto in E Major, BWV 1042, may date from Cöthen, and was transcribed as the Harpsichord Concerto No. 3 in D Major, BWV 1054. The five multiple Harpsichord Concertos, three for two, BWV 1060-62, and two for three claviers, BWV 1063-65, date to 1730, and the eight solo Harpsichord Concertos, BWV 1052-59, were compiled as a collection in 1738, presumably also for the Collegium. During the 1730s, Bach also composed sonatas/pieces, with obbligato harpsichord or continuo, for flute, BWV 1030-35 (http://bach-cantatas.com/NVD/BWV1030-1035-Gen3.htm); violin, BWV (1021, 1023, 1026, http://bach-cantatas.com/NVD/BWV1014-1023-Gen3.htm), and viola da gamba (BWV 1027-29, http://bach-cantatas.com/NVD/BWV1027-1029-Gen3.htm), says Wolff (Ibid.: 106, 110). Except for the solo harpsichord concertos, Wolff does not discuss these works in any detail since they were not part of collections.

11 BWV 1019 score and recording, Google Search Results.

12 Stephen Daw, "Bach: Sonatas for Violin and harpsichord," liner notes (Colchester GB: Chandos, 1997), https://www.chandos.net/products/catalogue/CHAN%200603.

13 The wealth of trio settings, original and transcription, are found at "Organ Music: Transcriptions, Part 1, Sebastian's Concertos, Trios, Sonatas, etc.," http://bach-cantatas.com/NVD/Organ-Music-Trans1.htm.

—————

To Come: Christoph Wolff, Bach's Musical Universe, Chorale Cantata Cycle, "The Most Ambitious of All Projects." |

|

Jeffrey Solow wrote (May 26, 2020):

[To William L. Hoffman] When I read Wolff's book I had a problem with this statement - "probably the violoncello as well" - in that it is based on no historical evidence that I have seen or heard of, and although it appears to be a complete supposition, is sourced as evidence that Bach played the cello. |

|

William L. Hoffman wrote (May 26, 2020):

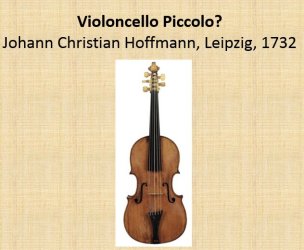

Wolff's statement on page 67 that Bach played "probably the violoncello as well" as the violin and viola, is explained on page 68: "There are no specific references to Bach's cello playing, but his expert and idiomatic treatment of the instrument as a composer strongly suggests his thorough familiarity with the cello as well." On Page 96 in his discussion of the cello suites, Wolff cites Bach's estate collection to include "three violas, a 'Bassetgen' (violoncello piccolo or viola pompous), and two violoncellos" (NBR 252). Cellist Boris Pergamenschikow says: <<I don't believe that the cello suites were primarily intended for instructional purposes, like many of Bach's clavier works. They are rather a kind of "glass bead game," music that cleanses the soul, especially if you play it yourself, preferably without any audience" (https://www.bach-cantatas.com/NVP/Pergamenschikow-B.htm). |

|

Kim Patrick Clow wrote (May 26, 2020):

[To Willian Hoffman] Speaking of Bach violin playing, and the great skills of composers and performed prior to Bach that influenced him, and this is a new name for me,

Johann Paul von Westhoff (1656 – buried 17 April 1705). |

|

|

|

He was a violinist based in the Dresden court and composed some of the earliest music known for the solo violin (unaccompanied). The Wikipedia entry states:

"He worked as musician and composer as a member of Dresden's Hofkapelle (1674–1697) and at the Weimar court (1699–1705), and was also active as a teacher of contemporary languages.

Westhoff's surviving music comprises seven works for violin and basso continuo and seven for solo violin, all published during his lifetime. More works, particularly a 1682 collection of solo violin music, are currently considered lost. His work, together with that of Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber and Johann Jakob Walther, greatly influenced the subsequent generation of German violinists, and the six partitas for solo violin inspired Johann Sebastian Bach's famous violin sonatas and partitas.

Westhoff's reputation was extremely high during his lifetime. Contemporaries ranked him, along with Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber and Johann Jakob Walther, among the best German violinists of the era. Already in 1671, at the age of 15, he was so well-connected that he became a tutor to two Saxon princes,[2] Johann George and Friedrich August. His influence must have spread wide, too, since journeys took him to numerous countries: Hungary, Italy, France (where he played before Louis XIV in 1682), the Dutch Republic, and the imperial court in Vienna.

Westhoff's 1683 suite is the earliest known multi-movement piece for solo violin. Along with the six solo partitas, it was an important forerunner of Johann Sebastian Bach's celebrated Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin. These were started during Bach's Weimar years and finished some 24 years after the earliest known print of Westhoff's partitas; the musical characteristics seem to show that Bach's work was at least conceptually indebted to Westhoff's.[4] Westhoff's violin writing is highly advanced, featuring double stopping up to the fourth position. Westhoff's solo violin music is distinctly German, with dense polyphony and robust themes, but the continuo sonatas show a pronounced Italian influence."

The new CD of Westhoff's music is released on the Ricercar label, and features the playing of Plamena Nikitassova, who uses the style of not holding the violin on her shoulder but lower down on her arm. A musiclogist friend was effusive about the CD and Plamena's playing. You can see her performing the music in this video clip: https://youtu.be/FDMLeYhS2Os |

|

Jeffrey Solow wrote (May 27, 2020):

[To Willian Hoffman] Being familiar with an instrument well enough to compose for it does not necessitate your ability to play it. I find it hard to believe that if he really played the cello (not just able to make sounds on it with fairly good intonation) C.P.E. Bach would have mentioned that in his Necrologue for JSB. (Pergamenshikow was a great cellist, but his comment has no bearing on what instruments Bach may have played.)

I am more and more coming to believe that the (infamous) Viola Pomposa and the Violoncello Piccolo were one and the same -- a 5-string viola-like instrument that was played like a violin and NOT the same instrument as the "Violoncello with 5-strings" called for in the Suite #6. As such, Bach may have been able to play it. (Anner Bylsma theorized that Bach may have played the Suites on the viola--entirely possible.) |

|

|

|

• Bach composed at least 8 cantatas that called for the violoncello piccolo including three before Source B (Kellner's copy) of the Suites, BWV 115, 41, and 58.

• In BWV 41, the piccolo cello is incorporated into the violin part.

• Bach used bass, tenor, alto, treble, and clef in his various piccolo cello parts.

• A Cöthen instrument inventory from 1773 lists “Ein Violon Cello Piculo mit 5 Seiten von J. C. Hoffmann 1731” |

|

David Stancliffe wrote (May 27, 2020):

[To Jeffrey Solow] My own experience of having performing all the Cantatas that include a part for violoncello piccolo is that that one size doesn't fit all. Not only does the part in which the piccolo obligato's music is included vary as well as the clef in which it is written but the kind of music does too. Some (as in BWV 41.iv) have a more filigree, arpeggiated style while others (like BWV 6.iii) have a more strongly melodic character.

I suspect that there was a much more fluid understanding of which instruments counted as what than our current tidy classifications allow. There is Sigimund Kuijken - essentially a violinist - playing what he calls a violoncello da spalla in a number of his recordings of cantatas, where otherwise the basso continuo line is played at 8' on a basso da viola - a more Italianate bass violin style of violin. There is Mario Brunello playing the Sei Soli on a 'violoncello piccolo' modelled on an instrument by the Amatis of Cremona dated between 1600 and 1610. His recording of the Sei Soli on Arcana 469 has an extended essay in the booklet by Peter Wollny (2019) on 'Johann Sebastian Bach and the Violoncello piccolo.'

To look at a parallel in parts calling for violas. especially in early cantatas where two viola parts are not uncommon, and in some cantatas in the Altbachische Archiv the violas are violas da gamba rather than da bracchio . In BWV 106, the well-known 'Actus Tragicus', those parts are clearly and universally understood to be for viola da gamba, and are frequently played on two bass viols. Yet the clefs indicate that they would most naturally be played one bass and on tenor viol. Not dissimilar to the figurative writing in especially 106.iii is the figurative writing in BWV 131 (Aus der Tiefe) in section iii. I have normally played these two 'viola' parts on violas da bracchio, but recently (in a concert with BWV 106) experimented with violas da gamba, and was pleased with the result. I was then interested to see that Van Veldhoven in the All-of-Bach Youtube performance of BWV 131 did the same - using gambas rather than violas.

I suspect that a more long-sighted overview of which instrument was used when in the period from 1600 to 1730 would give use a good deal of lattitude as instruments were being developed and made to fill the needs of the string ensembles that were evolving from a viol consort with violins on top, through the Germanic five-part string ensemble of the later 17th century before settling in the still current orchestral sound of two violin, viola, v'cello and double bass. |

| |

|

Continue on Part 2 |

|

Christoph Wolff : Short Biography

Piano Transcriptions: Works | Recordings

Books: The Bach Reader / The New Bach Reader | The World of the Bach Cantatas | Johann Sebastian Bach: The Learned Musician | Bach's Musical Universe: The Composer and His Work: Details & Discussions Part 1 | Discussions Part 2 | Discussions Part 3 |

|

|