The Portrait of Bach That Was Lost In World War Two -

An Authentic "Alternative" to the Haussmann Image of Johann Sebastian Bach in his early 60s Pages at The Face Of Bach

Page 4 - If The Berlin Portrait is Contemporaneous With The Haussmann Portraits, For Whom and Why Was It Painted?

The Face Of Bach

This remarkable photograph is not a computer generated composite; the original of the Weydenhammer Portrait Fragment, all that

remains of the portrait of Johann Sebastian Bach that belonged to his pupil Johann Christian Kittel, is resting gently on the surface

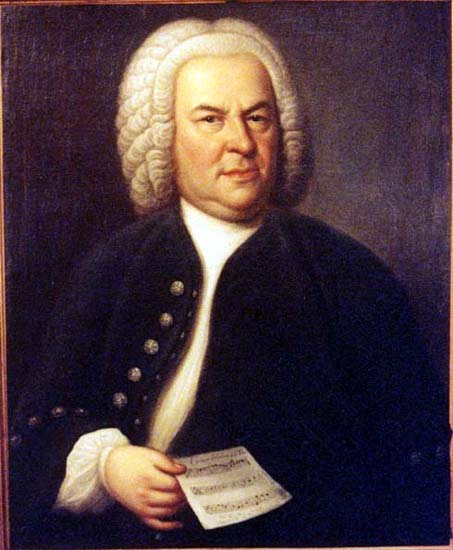

of the original of the 1748 Elias Gottlob Haussmann Portrait of Johann Sebastian Bach.

1748 Elias Gottlob Haussmann Portrait, Courtesy of William H. Scheide, Princeton, New Jersey

Weydenhammer Portrait Fragment, ca. 1733, Artist Unknown, Courtesy of the Weydenhammer Descendants

Photograph by Teri Noel Towe

©Teri Noel Towe, 2001, All Rights Reserved

The Portrait of Bach That Was Lost In World War Two

An Authentic "Alternative" to the Haussmann Image

of Johann Sebastian Bach in his early 60s

Page 4

If The Berlin Portrait is Contemporaneous With The Haussmann Portraits,

For Whom and Why Was It Painted?

Admittedly, the posthumous reputations for forensic iconographical accuracy of the two authorities who "discovered",

"authenticated", and provided the limited provenance for the painting may be less than unblemished, but, even so, we still must deal

with the astonishing reality that the Berlin Portrait passes the anatomical tests to a degree sufficient to confirm that, no matter what

its origins may have been, it is an accurate depiction of Bach in his early 60s.

Let us put on our rose-tinted glasses and assume, arguendo, that the Berlin Portrait was a portrait from life of Johann Sebastian

Bach that was contemporaneous with the Haussmann Portraits, particularly the 1748 version. Is there anything else about it that

might provide collateral, circumstantial evidence that it, in fact, depicts Johann Sebastan Bach? Can a convincing hypothesis be

offered for its existence?

In the Berlin Portrait, Bach displays no attribute to tell the viewer who he is or what his station in life is. Like the Bach of the

Volbach Portrait, the Bach of the Berlin Portrait does not proffer a copy of the Canon triplex à 6 vocibus to the viewer, as the

Bachs of the 1746 and 1748 Haussmann portraits do. Furthermore, there is no apparent, universally understood symbol of either

profession or position in life to be found in the standard three-quarter bust portrait pose. Still, although the clues are difficult to find

and analyze in that lone, murky photograph of the painting, an analysis of Bach's garments arguably yields a startling bit of

supportive evidence.

The lower left hand corner of the photograph is especially dark, and it is simply not possible to determine whether the outer garment

is a great coat or a dress coat of some kind, but, whichever it is, it has a lining of a lighter color, and the buttons appear to be of

cloth, rather than of metal. The same applies to the coat or waistcoat beneath. Also, the edges and the buttonholes of both garments

are piped in a lighter color on the outside. This latter design pecularity makes it possible to count the button holes and count them

accurately. There are six buttonholes visible on the inner coat and eight on the outer one:

The six button holes on the inner garment are easy to count. Those on the outer garment take much more patience to sort out

accurately, but a complete and accurate count is possible, the poor photograph notwithstanding, by carefully matching up the

buttonhole piping on the outside with the equivalent dark slits on the inside, where either one, or both, are visible. Beginning at the

top, on the inside, there are two complete slits and portions of two more visible beneath them; the piping on the button holes on the

outside of the garment begins to be visible with the third buttonhole, and there are a total of six such piped buttonholes visible in

whole or in part. I offer, therefore, the following button hole count, starting at the top of the garment, and working downwards,

describing each buttonhole and the portions of it that are visible, as the "roll" of the collar of the garment diminishes and disappears:

1. One complete buttonhole on the inside;

2. One complete buttonhole on the inside;

3. The outer end of the buttonhole is visible on the inside, the piping of the inner end is visible on the outside;

4. The outer end of the buttonhole is visible on the inside, the piping of the inner end is visible on the outside;

5. A tiny bit of the outer end of the buttonhole is visible on the inside, a proportionately larger amount of the piping of the inner end

is visible on the outside;

6. None of the inside of the buttonhole is visible, but a significant portion of the piping on the outside is visible;

7. One complete buttonhole on the outside; and

8. One complete buttonhole on the outside.

Thus there are eight buttonholes on the outer garment, in addition to the six on the inner garment. 8+6=14. Anyone who has spent

any time studying Johann Sebastian Bach is well aware of his obsession with numbers, numerology, and numerological equivalents,

and also knows that the Bach number is 14 (B=2 + A=1 + C=3 + H=8 = BACH=14). I, for one, cannot believe that the total of 14

buttonholes is a coincidence. As he did when he posed for the Volbach Portrait, which I believe must be treated as a genuine

portrait of Bach from life until proven otherwise, Bach signaled the knowledgeable viewer with a "sartorial" puzzle canon. {:-{)} In

the case of the Volbach Portrait, the pertinent detail of which is shown on the left, there are 14 buttons on the waistcoat and seven

(half of the Bach number) on the jacket.

Let us keep our rose-tinted glasses on and continue to assume, arguendo, that the Berlin Portrait was a portrait from life of Johann

Sebastian Bach that was contemporaneous with the Haussmann Portraits, particularly the 1748 version. Can a convincing

hypothesis be advanced to explain why and for whom the portrait was painted?

Besseler argued that the Berlin Portrait, which the Kunsthandlung Meyer & Ernst catalogue had described as, "....In dem

Originalzustand auf dem alten Keilrahmen und dem prächtiger Originalrahmen," ["in original condition on the old wedge stretcher

and in the splendid original frame"] most likely was commissioned by and paid for by Hermann, Count von Keyserlingk

(1696-1764), one of Bach's most fervent and influential admirers, the man for whom, according to the well loved and almost

certainly authentic anecdote, the so called "Goldberg" Variations, BWV 988, were composed.

That conjecture remains an excellent possibility in spite of Bessler's failure to present a convincing argument on its behalf. By dating

the painting at around 1740, Besseler was put in a position in which he had to argue that the Berlin Portrait was the work of one of

the portrait painters who was active in Dresden, where Keyserlingk was then the Imperial Russian Ambassador to the Saxon

Electorate and the Polish Kingdom. The painting, however, could not be convincingly attributed to any portrait painter known to

have been active in Dresden at the time.

However, if one considers the Berlin Portrait to be contemporaneous with the two Haussmann portraits, a whole new series of

arguments in support of Besseler's hypothesis that the Berlin Portrait was painted for Count von Keyserlingk manifest themselves.

In 1745 or 1746, Elizabeth, the daughter of Peter the Great and Tsaritsa from 1741 until her death in 1762, transferred Count von

Keyserlingk from the Court in Dresden to the Court in Berlin. One of the repercussions of the transfer was that the Count was no

longer a resident of the same country of which Bach was a resident; another was a substantial increase in the physical distance that

separated them. There is plenty of independent evidence to support the contention that the two men were as close friends as the

difference in their social stations would then permit. It is likely that the Count was one of the individuals instrumental in securing

Bach's invitation to perform for Frederick the Great in Potsdam in May, 1747; in fact -- and I am by no means the first to advance

this suggestion -- the appearances that Bach made at the Court of Frederick II could, to a significant degree, have been motivated

and expedited by the Count's assertion that for one of the Saxon Hofcompositeurs to make a visit to the music loving King of

Prussia, at whose court one of that composer's sons was employed, would be a cordial and politically harmless diplomatic gesture,

coming as it did so close on the heels of the cessation of hostilities between Prussia and Saxony.

The exact duration of Bach's visit to Potsdam and Berlin in May, 1747, is not certain, but he has to have stayed for a minimum of

four days, and it is possible that he stayed for a week to ten days. He could have stayed no longer than that, however, because we

know that he was back in Leipzig in time to take Holy Communion on May 18. But, even had the visit been of but four days'

duration, there would still have been time for the sittings that were required for the face, especially if the artist came to Bach, rather

than the Bach going to the artist's studio. The balance of the portrait could have been filled in easily after Bach's departure. And, if

the portrait was commissioned on very short notice by the Count, a devoted patron now very much uncertain when he will see his

treasured musician friend again, if ever, a portrait painter of less than the top rank might have been the only available option. To

Keyserlingk's frustation, and probably also to Bach's, all of the best painters already had been "fully booked" by other clients. Such

a practical consideration easily explains the initial inconsistency of a second rate portrait in an expensive first rate frame. A plausible

scenario: Keyserlingk commissioned the portrait from Antoine Pesne, the Court Portrait Painter, who was simply too busy with

other commissions to undertake the portrait himself and dispatched one of the journeymen in his studio to do the job.

The details of this hypothesis, which makes the nickname The Berlin Portrait especially fitting, remain to be tested, and the facts

supporting it need to be checked, of course, but, at the very least, it is a good beginning. Among the matters that need to be looked

into in this context: Can the style of the as yet unidentified artist be matched to that of any portraitist known to have been active in

Berlin and environs in 1747, like the aforesaid Antoine Pesne or any of his pupils, for example? Do any inventories of the

possessions or of the Estate of the Count von Keyserlingk survive that would confirm the existence of such a painting in his

collection?

Please click on  to go on to Page 5.

to go on to Page 5.

Please click on  to return to the Index Page at The Face Of Bach.

to return to the Index Page at The Face Of Bach.

Please click on  to visit the Johann Sebastian Bach Index Page at Teri Noel Towe's Homepages.

to visit the Johann Sebastian Bach Index Page at Teri Noel Towe's Homepages.

Please click on the  to visit the Teri Noel Towe Welcome Page.

to visit the Teri Noel Towe Welcome Page.

TheFaceOfBach@aol.com

Copyright, Teri Noel Towe, 2000 , 2002

Unless otherwise credited, all images of the Weydenhammer Portrait: Copyright, The Weydenhammer Descendants, 2000

All Rights Reserved

The Face Of Bach is a PPP Free Early Music website.

The Face Of Bach has received the HIP Woolly Mammoth Stamp of Approval from The HIP-ocrisy Home Page.