The Portrait of Bach That Was Lost In World War Two -

An Authentic "Alternative" to the Haussmann Image of Johann Sebastian Bach in his early 60s Pages at The Face Of Bach

Page 2 - Physiognomical Comparisons

The Face Of Bach

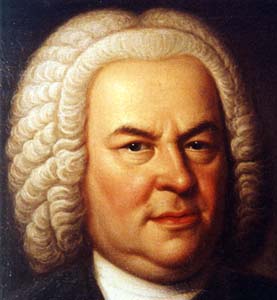

This remarkable photograph is not a computer generated composite; the original of the Weydenhammer Portrait Fragment, all that

remains of the portrait of Johann Sebastian Bach that belonged to his pupil Johann Christian Kittel, is resting gently on the surface

of the original of the 1748 Elias Gottlob Haussmann Portrait of Johann Sebastian Bach.

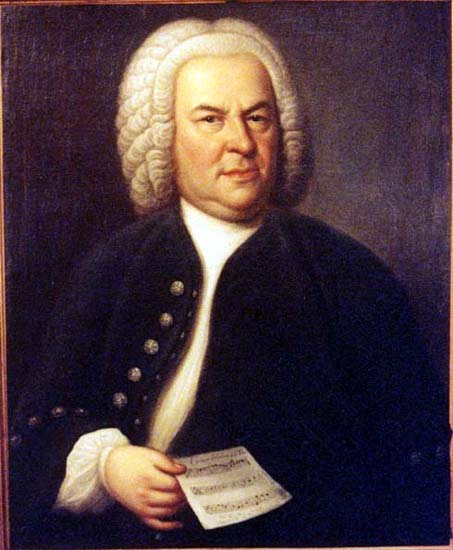

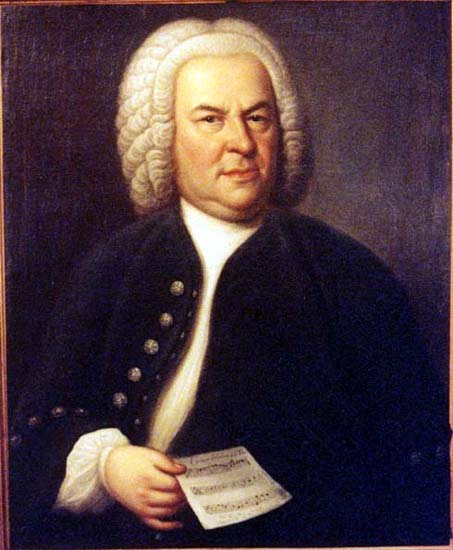

1748 Elias Gottlob Haussmann Portrait, Courtesy of William H. Scheide, Princeton, New Jersey

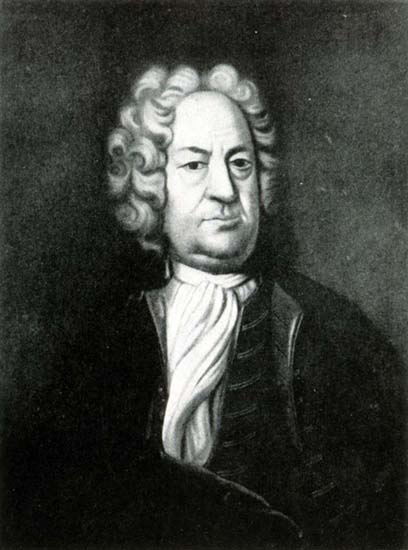

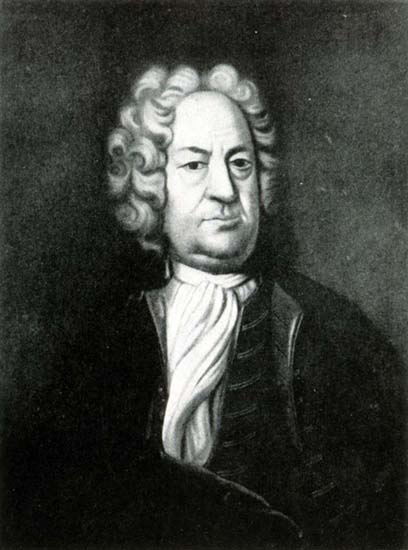

Weydenhammer Portrait Fragment, ca. 1733, Artist Unknown, Courtesy of the Weydenhammer Descendants

Photograph by Teri Noel Towe

©Teri Noel Towe, 2001, All Rights Reserved

The Portrait of Bach That Was Lost In World War Two

An Authentic "Alternative" to the Haussmann Image

of Johann Sebastian Bach in his early 60s

Page 2

Physiognomical Comparisons

So, let's start by putting the Berlin Portrait through the same kind of comparison through which I have so far put the

Weydenhammer Portrait Fragment, the Volbach Portrait, the Group Portrait, and the Portrait in Erfurt that is alleged to depict Bach,

the Weimar Concertmeister. Using the 1748 Haussmann Portrait as the standard, let's see how the Berlin Portrait measures up as an

accurate depiction of Bach's physiognomical characteristics as they are agreed to be.

The physiognomical characteristics that traditionally have been considered essential to an accurate depiction of Bach's face are:

- A massive skull,

- A receding forehead,

- drooping eyelids, particularly over the right eye,

- shallow eye-sockets,

- unusual asymmetry of the eyes,

- predominantly blue color of the eyes, and

- protruding jaw and double chin

To this list, I would add another four, some of which, arguably, are refinements of traditional ones:

- a distinctive and asymmetrical furrowed brow that gives Bach an aura that is at once severe and mischievous,

- the long nose with what appears to be a slight arch about a third of the way down the bridge. (This part of the

nose is one of the anatomical details for which the 1746 Haussmann painting is particularly unreliable.)

- the distinctive shape of the mouth, the lower lip, and the crease at the right side of the mouth. This aspect of

Bach's face is particularly distinct in the 1748 Haussmann.

- the distinctive outline of the cheekbone and the jaw on the left side of the face, an outline that can be perceived

clearly in the boundaries between light and shadow on the face.

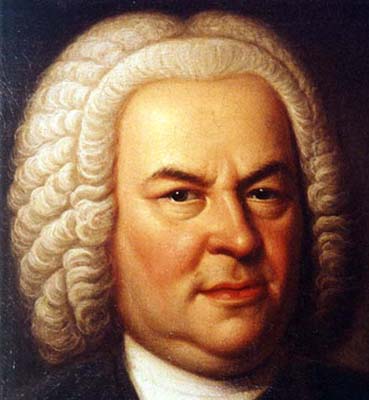

The image that is the standard for comparison is the 1748 Haussmann Portrait:

Both portraits portray a Bach of almost exactly the same weight, and the contour of the left shoulder appears to be identical.

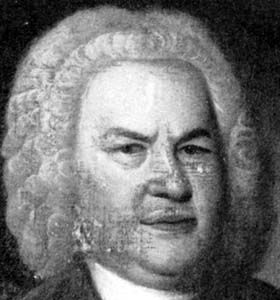

Now, just the heads:

The image on the left is a detail from a photograph of the 1748 Haussmann portrait that I took in Princeton in early November,

2000; this detail is what I call a Weydenhammer Equivalent; the image on the right is the Weydenhammer Equivalent from the

version of the photo of the Berlin Portrait that appears as a full page illustration in Heinrich Besseler's 1959 Bach Jahrbuch article

on the various Bach portraits. For the sake of completeness, even though the painting has been damaged so heavily and overpainted

so many times, the 1746 Haussmann Portrait must be included. As a physiognomical standard, the painting can be used only in its

unrestored state, and then, essentially, only as a confirmation or as a reminder of those areas in which the painting is completely

unreliable. The Weydenhammer Equivalent of the 1746 Haussmann Portrait, from a photograph of the painting with all of the

overpaint removed that was taken in 1914, is now added to the equation for those restricted purposes.

Before I address, and address in detail, the astonishing similarities between the two faces, let me comment on the glaring "apparent"

anomaly -- the unusual short perruque that Bach is wearing in the Berlin Portrait. The Haussmann image is so firmly ingrained in our

souls that the notion of Bach in anything other than a full, white wig, makes us bristle, almost instinctively. I have addressed the

issue of Bach in a short perruque in in detail in the Queens College Lecture; so, for the purposes of this discussion, a portrait of a

man in a short perruque cannot be disqualified as an authentic portrait from life of Johann Sebastian Bach on that ground alone.

The possibility that the faces of the Haussmann portraits and the face of the Berlin Portrait are one and the same becomes even

more apparent when one studies just the faces, without the distractions of the perruques and the clothing.

The distinctive outline of the cheekbone and the jaw on the left side of the face, an outline that can be perceived clearly in the

boundaries between light and shadow on the face in the 1748 Haussman Portrait (This portion of the face of the 1746 Haussmann

Portrait is not in good condition and therefore has little probative value.), is for all practical purposes identical in the Berlin Portrait.

Both faces are the faces of heavy men, and the distinctive shadow that the "upper" chin casts on the "lower" is also nearly identical.

Having enumerated and described the physiognomical characteristics of Bach's face that must be taken into consideration in

evaluating any image that is claimed to depict accurately the face of Johann Sebastian Bach, let me now compare these three faces,

anatomical detail by anatomical detail, starting at the top and working down. Descriptions that refer to "left" or "right", are from

Bach's perspective, not the viewer's, unless otherwise indicated. The 1748 Haussmann Portrait is the top, or lefthand, image, the

1746 Haussmann Portrait is the bottom, or righthand, image, and the Berlin Portrait is the middle image.

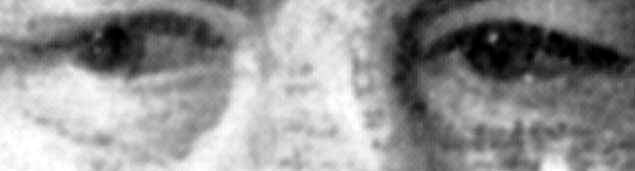

First, the distinctive furrowed brow:

The same distinctive asymmetry is in evidence. In all three paintings, the right brow meets the bridge of the nose almost exactly the

same distance above the point at which the left brow meets the nose. Furthermore, the distinctive upward creases in the skin where

the brows meet the bridge of the nose are evident in all three paintings.

Next, the eyelids and eyes:

Once again, the simlarities are immediately apparent.

First, the fully developed ptosis (or blepharochalasis) that is so much a hallmark of the Haussmann depiction of Bach can be

clearly seen. Also,in all three images, the development of the ptosis in the left eye lags behind the development of the ptosis in the

right eye.

Second, please note, especially when one takes into consideration how realtively unskilled the unidentified painter appears to have

been, the remarkable similarity between the shapes of the lower right lids in all three paintings. There is a distinctive "curve" just to

the viewer's left of the point at which the lid meets the nose that can be seen clearly in both the 1748 Haussmann and the Berlin

Portrait. Although it is a bit blurry in the blown-up detail of the photo of the unrestored 1746 Haussmann, this distinctive quirk is

still clearly discernible. The distinctive, and very much different configuration of the left eye where it meets the nose is remarkably

similar in all three. Finally, the irises of the Berlin Portrait's eyes appear to be abnormally large, like the eyes of the 1748 Haussmann

Portrait, and the subtle detail of the "wall-eyed" right eye has also been captured.

Next, let us have a look at the bags under Bach's eyes.

The 1746 Haussmann is of little value because of its poor condition in this area, but, even so, one can make out the distinctive

semicircular curve that begins at the nose end of the right eye. There is enough detail in the photograph of the Berlin Portrait to

make it possible to trace not only that curve but also the distinctive and anomalous shape of the bags under under the left eye that is

clearly visible in the 1748 Haussmann.

Next, the nose:

Once again, the similarities are immediately apparent. The distinctive arch on the left side of the nose is seen in clearly in the details

from the 1748 Haussmann and the Berlin Portrait despite the somewhat "washed out" detail, and the essential shape and flair of the

right nostril seem very much the same. The 1746 Haussmann, alas, has negligible probative value because of the severe paint loss to

the nose, especially the bridge.

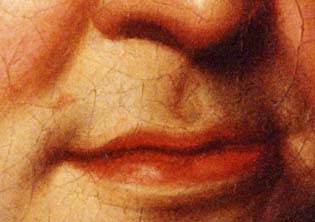

Now, the mouth:

I have added a detail of the frontal photograph of the skull to aid in this comparison. I have also included the 1746 Haussmann,

although its probative value is minimal because of all the surface damage and abrasion in this area. Once again, the similarities are

striking. The tight, deep creases where the lips meet the cheeks are identical, and the lower jaw clearly extends beyond the upper in

the Berlin Portrait, as it does in both of the Haussmann portraits and the skull. It should also be noted that the contour of the upper

lip follows that of the 1748 Haussmann almost exactly, and that this contour accurately reflects the evidence provided by the skull

regarding Bach's dentition.

An important secondary issue that affects the comparison of the appearance of Bach's mouth is the question of the number of teeth

that were actually still in his jaws at the time that a given portrait was painted. Bach's skull is missing quite a few teeth, and, although

one must allow for the probability, if not the certainty, that teeth may have been lost after burial (The skeleton is incomplete, to

begin with, and the condition of the upper jaw suggests that the upper lateral and central right teeth, and perhaps the upper left

lateral were dislodged and lost either during the 144 years of interment or during the exhumation process.), the configurations of the

mouth in both the Meiningen Pastel and the 1748 Haussmann Portrait confirm that there were teeth missing, but the condition of the

upper and lower jaws also confirms that there was intermaxillary support that prevented total collapse and a "toothless" look. The

need to allow for and compensate for the uncertainties of the state of Bach's dentition at various times of his life complicates any

authentication process, since, at least until the appearance of the Weydenhammer Portrait Fragment, which I have demonstrated

conclusively is what remains of the long lost portrait of Bach that belonged to Kittel, all of our authentic standards for comparison

date from the end of his life.

But in the case of the Berlin Portrait, we appear to be dealing with a portrait of Bach that was painted towards the end of his life,

and that makes the almost identical contours of the upper lips in the two portraits that much more important.

If it is not the conclusion that must be drawn, the conclusion that easily can be drawn is that, if it is a portrait from life, the Berlin

Portrait, which has passed the essential comparative physiognomical tests, must show a Bach with the same, or nearly the same,

dentition as the Bach of the 1748 Haussmann Portrait.

Now, let us consider the implications of that conclusion.

Please click on  to go on to Page 3.

to go on to Page 3.

Please click on  to return to the Index Page at The Face Of Bach.

to return to the Index Page at The Face Of Bach.

Please click on  to visit the Johann Sebastian Bach Index Page at Teri Noel Towe's Homepages.

to visit the Johann Sebastian Bach Index Page at Teri Noel Towe's Homepages.

Please click on the  to visit the Teri Noel Towe Welcome Page.

to visit the Teri Noel Towe Welcome Page.

TheFaceOfBach@aol.com

Copyright, Teri Noel Towe, 2000 , 2002

Unless otherwise credited, all images of the Weydenhammer Portrait: Copyright, The Weydenhammer Descendants, 2000

All Rights Reserved

The Face Of Bach is a PPP Free Early Music website.

The Face Of Bach has received the HIP Woolly Mammoth Stamp of Approval from The HIP-ocrisy Home Page.