The Portrait in Erfurt Alleged to Depict Bach, the Weimar Concertmeister - Is this young man really Johann Sebastian Bach? Pages

at The Face Of Bach

Page 2

The Face Of Bach

This remarkable photograph is not a computer generated composite; the original of the Weydenhammer Portrait Fragment, all that

remains of the portrait of Johann Sebastian Bach that belonged to his pupil Johann Christian Kittel, is resting gently on the surface

of the original of the 1748 Elias Gottlob Haussmann Portrait of Johann Sebastian Bach.

1748 Elias Gottlob Haussmann Portrait, Courtesy of William H. Scheide, Princeton, New Jersey

Weydenhammer Portrait Fragment, ca. 1733, Artist Unknown, Courtesy of the Weydenhammer Descendants

Photograph by Teri Noel Towe

©Teri Noel Towe, 2001, All Rights Reserved

The Portrait in Erfurt Alleged to Depict Bach, the Weimar Concertmeister

Before the 1907 Restoration and As It Looked in 1985

Is this young man really Johann Sebastian Bach?

Page 2

After I completed the preliminary examination of the Volbach Portrait in late August, 2000, and had made some initial fine tunings to

the discussion of the painting, I turned my mind to other things; both my law practice and my perennial borders were in shambles,

and, besides, "breathers" are necessary in order to stay fresh and open-minded.

A couple of weeks later, while planting autumn crocus about three months late, I had a brainstorm about the Haussmann Portraits.

But I was not near the books that I needed to work on confirming the accuracy of the theory that had materialized in my mind so

suddenly. Several days later, when I once again had access to my library, I set out to find the books I needed. On the list were

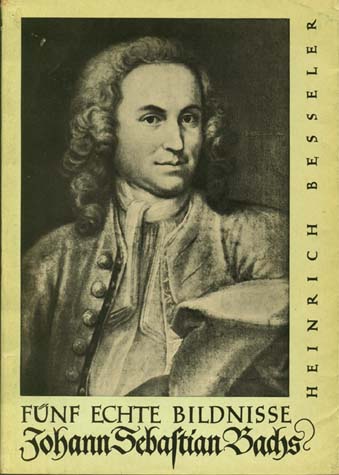

Heinrich Besseler's Fünf Echte Bildnisse Johann Sebastian Bachs, which I located without difficulty, and the 1914 volume of the

Bach Jahrbuch, which was nowhere to be found. I thought that I had a complete run of the Bach Jahrbuch, from the inception of

the Neue Bach Gesellschaft through the early 1990s. But to my annoyance, I could not find the volume for 1914. Because of their

small size, however, the Bach Jahrbuch volumes are precisely the kind of book that slips behind others on the shelf. I began to

take the books off the shelf to see if the 1914 volume was behind them. In the process, my eye fell on the cover of a paperbound

volume of similar size and thickness. I was taken by the novelty and invention of the lettering on the stark cover, redolent of the

disitnctive art deco style of the Weimar Republic:

I put the other books down. I carefully opened the cover of this fragile volume, printed on high acid content paper, and turned

gingerly to the title page. This is what I saw:

I stared at the frontispiece in astonishment. Before me was a high quality photogravure of the Erfurt Portrait in its unrestored state!

Not only had I not been able to remember where I had seen the photograph of the Erfurt Portrait in its "original condition", but also

I had forgotten that the image was to be found in a book in my own library. I remembered one of my Mother's maxims: "If you

can't find something, look for something else. Then you will find whatever it was that you started out to look for." (I also recalled

that this book was a part of a large library of books on Bach that I was lucky enough to be able to buy "en bloc" from a second

hand book dealer, because my friend and colleague at Ovation, Bradley Chase, had tipped me off to it. Thanks again, Bradley!)

All of a sudden, testing the validity of the brainstorm about the Haussmann Portraits could wait, and my frustration at my inability to

find the 1914 volume of the Bach Jahrbuch had vaporized. Excitedly, I began to study the photogravure, which, while it is larger

than I had remembered, is rather small. Of course, when I went back to my country house in Rhode Island the following day, I had

both the Beyer volume and Besseler's monograph in my luggage.

Initially, the realization that it would be unreasonable to expect ever to see a better photograph of the Erfurt Portrait in its unrestored

state and that I thus was dealing with the best possible reproduction of the original photograph of the unrestored canvas that I could

reasonably anticipate finding led me to focus on the details. How would the eyelids, the nose, the brow, the mouth and jaw compare

with their counterparts in the 1748 Haussmann Portrait, the Weydenhammer Portrait Fragment, the Meiningen Pastel, and the

Volbach Portrait? What would the side by side comparisons reveal?

I gave no consideration to anything but the details of the Bach physiognomy until after I had carefully laid the book, open, on the

scanning bed to begin the process of creating the kind of computer generated reference images that are essential to my

methodology in evaluating the Bach Portraits.

Finally, I got to the scan of the face, and the face alone, without the distractions of the wig and the costume.

It was then that the anomaly hit me, and it struck me like the clichéed bolt of lightning. With the recognition of the anomaly came the

realization that the anomaly had to have been suppressed deliberately when the painting was restored in 1907.

Here is the face, "then" and "now":

First, I saw that in touching up the face, the restorer had added flesh to the lower left cheek. As the photograph that is reproduced

in Beyer's book clearly shows, the lower portion of the face was nowhere near as "fleshy", and the as yet unidentified sitter had a

lower jaw that was significantly narrower and more pointed than Bach's. A concomitant bit of restorative legerdermain can be seen

on the right jaw. It original narrowness has been softened by the subtle reshaping of both the right jaw and the collar of the stock

that is wrapped around the sitter's neck.

Like a garment unraveling after the crucial thread has been pulled, the Erfurt Portrait's credibility as an authentic depiction of the

face of the young Johann Sebastian Bach began to disintegrate, and it disintegrated quickly. I have little doubt, for example, that the

nose was deliberately but subtly altered in the restoration process; not only does the bridge appear to have been free of the ridge

that now is to be seen in this pseudo-Bach's nose, but also the shadow at the bridge of the nose has been lightened to make the

junction of bridge to brow seem less abrupt. In short, a restoration of the nose as a nose that was significantly more aquuiline

probably would have been more accurate, and certainly no less accurate, than the more "Bachian" nose of the restored face. Finally,

it appears that the darkness of the shadow on the upper lip has been carefully lightened and the shape of the left-hand end of the

upper lip altered to make what may well have been an overbite look more like an underbite.

But some of these are subtle differences, and they could be at least in part the result of the potentially unfair comparison of a black

and white photograph with a color one.

I returned to the scanning bed. This time, I turned to the Besseler monograph for the source of a high quality black and white

photograph of the painting in its restored state. After all, Besseler thought enough of this painting to put it on the cover of the book:

Here, then, is a black and white comparison. On the left, the face of the unrestored canvas, from the Beyer frontispiece; on the

right, the face from the black and white photograph in the Besseler monograph:

If anything, the extent of the restorative "legerdemain" is even more apparent.

The harsh reality of my discovery sank in slowly, but it sank in bitterly.

I had hoped that locating the photograph of the unrestored painting would enable me to remove doubt, but I had hoped for a

different result when the doubt was removed.

It is a bitter pill, but it is one that must be swallowed.

Sadly, the Erfurt Portrait is the product of deception, a carefully considered and carefully calculated deception. Its "discoverers"

and its "restorers" sought to capitalize on a fortuitous opportunity, and, after careful assessment of the available knowledge, they

capitalized on the opportunity, secure in the belief that they would get away with it.

And until now, they have gotten away with it

Please click on  to go on to Page 3.

to go on to Page 3.

Please click on  to return to the Index Page at The Face Of Bach.

to return to the Index Page at The Face Of Bach.

Please click on  to visit the Johann Sebastian Bach Index Page at Teri Noel Towe's Homepages.

to visit the Johann Sebastian Bach Index Page at Teri Noel Towe's Homepages.

Please click on the  to visit the Teri Noel Towe Welcome Page.

to visit the Teri Noel Towe Welcome Page.

TheFaceOfBach@aol.com

Copyright, Teri Noel Towe, 2000 , 2002

Unless otherwise credited, all images of the Weydenhammer Portrait: Copyright, The Weydenhammer Descendants, 2000

All Rights Reserved

The Face Of Bach is a PPP Free Early Music website.

The Face Of Bach has received the HIP Woolly Mammoth Stamp of Approval from The HIP-ocrisy Home Page.